North Texas artist Joshua Goode is exploring new media with his signature style in his latest exhibition Joshua Goode: The Ruins of Burg Worth at Fort Works Art. Over the past decade, Goode has explored the creation and manipulation of historic narratives in a distinctively humorous manner with staged excavations and created artifacts. I spoke with Goode to discuss the evolution of his project over the years and the present significance of these themes.

Megan Wilson Krznarich (MWK): I am fascinated by your concept of creating artworks presented as artifacts from an ancient Aurora Rhoman culture based in the present-day Fort Worth area. You also construct fantastic stories of the potential uses of some of these “artifacts.” When I saw the works I was like, how did he ever come up with this idea? So how did you get started with this concept? I know you’ve explored this concept for a few years now.

Joshua Goode (JG): Originally, post graduate school, I was creating tombs. I have a sister who has some severe disabilities and I was faced with her mortality. It made me very aware of trying to acknowledge and remember people. How do you create immortality? How do you honor someone’s memory and their legacy? So, it started out really as making tombs for her. I was building them thinking of the Mycenaean and Egyptian tombs where we put all of someone’s personal belongings into a space. It was a little dark.

In 2011, I ended up receiving the Dozier Travel Award from the Dallas Museum of Art after making a few of these installations. I proposed to go study funerary practices of prehistoric people. I was really fascinated to see how others — our ancestors — dealt with the same issue. I was in the process of researching where to go, when I was connected through archaeologist friends to a real archaeology dig at Vogelherd Cave in Germany. This is where they found some of the earliest carvings made by humans out of mammoth ivory. The whole process was fascinating. I may have exaggerated my experience, but they just threw me next to all of these German archaeologists and gave me a square where I tried to dig and be as careful as I could be. Then, I pulled out this yellow rock. I was like, “Wow. It could be used to make a painting or drawing.” So, I asked the person next to me, really excited, “what is this?” He looks at it, picks it up, and says “Ah, that’s yellow ochre. Meh!” and tossed it like it was nothing. He didn’t care at all. That was a moment of discovery and reflection about being fascinated by something and assigning it great importance. He could have said anything else to me, and I would have believed him. He could have told me it was any kind of special, magical thing and I would have been even more excited.

I became fascinated with that process of discovery and validation. How does something gain importance and how do we determine that? Of course, that fit in perfectly with what I was already doing by using these personal artifacts and trying to give them importance to other people. The first time I tried out the idea was in Cairo. I set up these big leather baskets of salt. Salt has been very important for Egyptian culture and commerce. That’s where I started to make the chimerical figures using my childhood toys, which I cut up, melted back together, then spray painted gold. I had people dig up and discover these items in the salt, then go display them and give them names and characters. That was the first time all of these elements of the project came together. I was really fascinated by the process of collaborating with the audience. That’s what I was excited about installation work to begin with. I wanted to ask how do you engage, create an experience, and really open a conversation with somebody who is visiting your work?

MWK: So, you are intrigued by the participatory nature of installation. With that audience participation and engagement, there is also a performative nature to your work. This is especially present in this exhibition’s installation of a world map and photographs documenting your global “excavations.”

JG: I grew up with my family practicing Native American religion (Lakota Sioux), and looking for different ways to cope with my sister’s mortality. There were so many powerful, spiritual ceremonies that I was able to take part in and participate in. These were incredibly impactful to me, and I also became familiar with artists, like Joseph Beuys, who were embracing shamanistic power.

Also, I was fascinated with the Heyoka in Lakota Sioux ceremonies. The Heyoka is a sacred clown that serves as the foil and points out the absurdities of the world. In that performative aspect of my works, I play the fool. It should be ridiculous and you should laugh at me for thinking these things are real and making such bold claims. This element evolved further during the Covid-19 pandemic. Due to restrictions around travel and gathering, I turned to Instagram. I could easily stage a photograph and discovery, then engage with an audience. Most people get it and see the humor, but sometimes there are arguments over its factuality in the comments. Those that get it are quick to note that I am an artist and direct others to my page to demonstrate that I am not hiding the absurdity. This is another way in which people are invited to participate as well, pointing out that an excavation is fake.

MWK: This is an important distinction. You are inviting viewers in on the joke, so that they do not feel like the joke is on them. There is a lot of humor involved in your work, but it is also grounded in research. What role does the research play in your process?

JG: I love history and expanding my knowledge, especially of prehistoric history, the development of humanity, and how we are all connected. When I travel to a new location, it is a chance to learn something new and find a way to connect with a local audience. I want to address something that is very specific to their history.

In St. Petersburg, Russia, Peter the Great built the Kunstkamera, an anthropological and ethnographic museum filled with oddities. There were two-headed calves and fetuses with mutations, like with one eye or two heads. It was established in 1714 to educate people about these conditions and how they occur naturally, to dispel superstitious fear. So, in my project in St. Petersburg, I played with that history and made Two Headed T-Rex Skull (The Hydra). This project led to national media attention in Russia, where I was able to talk about issues of fake history, the need to check sources, and how people in positions of power can use history to shape how we view things. Considering recent events in Russia, it is really sad to reflect on, but I felt it was important to say that on the national news there.

By connecting with local history, my projects invite people in because they are familiar. They also point out that I am a fool and educate me on the real history. We have real discussions on their history, not the absurd version created by a silly American. Then other people in the audience will chip in with their stories. I love the interesting discussions and learning so many new things, but I find it also helps to expand the audience beyond those who would typically visit a gallery or a museum.

MWK: I love that sharing of power. In museums, we often discuss the need to break down the mantle of expertise. I appreciate how you’re going into communities and inviting them to share their wisdom, knowledge, and assert their expertise around their cultural stories. I think that’s a really lovely aspect.

Your project has really shifted and evolved over the years since you started. Fake news and fake narratives are very much in our awareness now.

JG: There has been a natural mutation of it over the years and it feels more urgent now. We’re clearly seeing the real-world effects of fake news, controlled narratives, and how easily we can shape how people act based on what they think their history is and what they want to return to. It is a fine line that I try to walk. “Am I contributing to a problem? Am I also creating fake news?” It is walking that line so people can tell that my excavations are fake and identified as fake. Hopefully, it will help them strengthen their critical engagement and identify false narratives.

This is also why I use characters from The Simpsons and other recognizable pop imagery in my artworks. This is also why the in-person engagement is so important, and I am always looking for the next location. It creates a different energy, a different dynamic, getting to talk with the community. Hopefully it impacts the way they look at themselves, their history, and lets them find commonalities with others. Humor and satire make it easier to address such serious ideas.

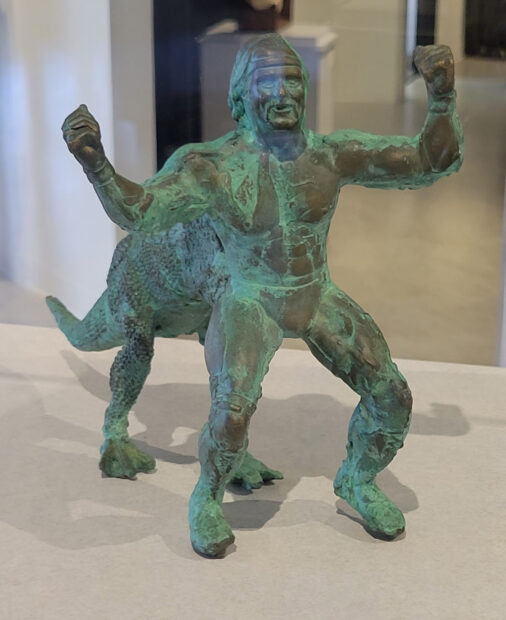

MWK: You mentioned your inclusion of pop culture characters, like the Simpsons and Hulk Hogan in Hulktaur. It struck me that although these are not from the ancient Aurora Rhoman era, as reported, they are still a bit dated at this point, from the 1980s and 1990s. Is there a reason you are referencing this particular era instead of more recent pop culture?

JG: It again goes back to my sister and my family. The Simpsons is a fantastic show that I fell in love with growing up, and it was a great comedic distraction that got me through some hard times. I had these objects as toys when I was a kid. All of these are personal artifacts that were really important to me. I wanted to recreate them, give them a universal importance, and an entire historical narrative. The 1980s nostalgia is there, because that was my childhood. Now there are some newer things I am dealing with, like SpongeBob. It is not that new, but my son is really into SpongeBob. So, I now integrate items that are or were important to my children.

MWK: It goes back to your earlier point about elevating the materials of everyday life and everyday people. That is a great way to connect with audiences as well, because the references are so familiar to many, at least of a certain age.

To continue diving into the artworks in the exhibition, could you share more about Rhoman Artemis and your particular interpretation of the Greek goddess?

JG: It is based on Artemis of Ephesus sculptures which have spherical objects covering their torsos, typically interpreted as breasts or bull testicles. I have always found truck nuts — large bull testicles attached to a truck — to be one of the most absurd things in southern United States culture. It is such an overly masculine, testosterone-fueled, boy-man concept. Rhoman Artemis was an opportunity to play with both of these ideas. And it was my first pandemic project. I always kind of had it in the back of my head, but I hadn’t wanted to take the risk of making a sculpture covered in truck nuts. It is a very tongue-in-cheek Texan reference to me. It also shows my sense of humor. I like to take something recognizable from art history, put my spin on it, and subvert it somehow where it still is recognizable, making it partially what it should be, but it also contains elements that clearly should not be part of it.

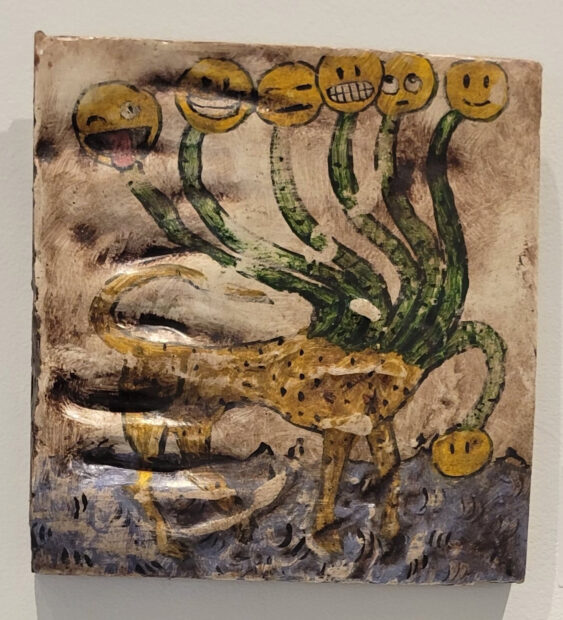

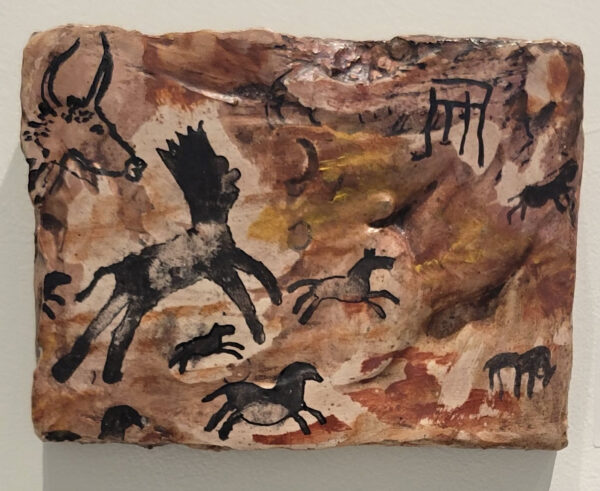

MWK: In the exhibition, there is a more recent body of plaster and mixed media works, including Hydra and Wildcat Hunting. What prompted the transition to working in this format?

JG: To be honest, as an artist I get bored just working in one medium. I am always looking for a new challenge and a new way to visualize my work. Cave paintings have long fascinated me, so I am trying to take on that language but keep sculpture as part of it. I am really into object making. I look at everything as an object. My academic background is in painting and I still teach painting. So, I am always trying to find a way to bring painting back into this concept. Playing with cave paintings was a way to keep that physicality and the idea of an artifact, while being able to introduce more of a painterly approach.

MWK: What are you hoping visitors will take away after seeing the exhibition at Fort Works Art?

JG: I hope they enjoy it and have a laugh. When I was first creating this type of work, people would come to me and ask if it was okay to laugh. They were nervous about offending me. I want them to laugh. It is supposed to be funny. That is the idea. I want people to feel comfortable having a different response to an art show, while still being able to deal with serious subject matter. I also want visitors to think about history, and to think about what they know and think of history. I hope they recognize references to art history and our local culture. You have to know where you have been and know where you are going to make change. I really want visitors to take that deep dive. Self-reflection on the history of a location is really important for growth. Hopefully, this will help us shape our future together.

Joshua Goode: The Ruins of Burg Worth is on view at Fort Works Art in Fort Worth through April 29, 2023.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

1 comment

Thanks for the read about tombs, ochre, Beuys, & power. Congratulations, Josh, on your recent shows locally & further afield!