This is the second piece of a multi-part series on Venice, written during the author’s month-long residency and personal hiatus in the city. To read part one, please go here.

Arriving by Vaporetto at the Giardini. Photo by Pilar Goutas.

Almost one week passed before I was able to see any art beyond the exhibition we brought and installed. I was itching to visit the Biennale, especially because I never expected the opportunity to see it.

I have spent decades going to, participating in, and working for art fairs, and I have curated two biennials in my day. And while my life has been all things art in almost every context, Venice in full bloom was unlike anything I had ever seen before.

Established in 1895, the Biennale was a means to attract tourism to the city at a time when it needed both an economic nudge and a reason to be on the intellectual map. The event has grown over the years in size, scale, and the amount of tourists it attracts, but the mere idea of building a building simply to display art once every two years baffles me. Even though it is never the scale of a mega museum, the investment of economy that goes into each pavilion is astounding, not to mention the investment in the production of each work of art. The original venue of the Giardini — now the smaller area of the Biennale — is home to one central exhibition space surrounded by 29 national pavilions representing the likes of Spain, Estonia, Australia, Venezuela…the list goes on.

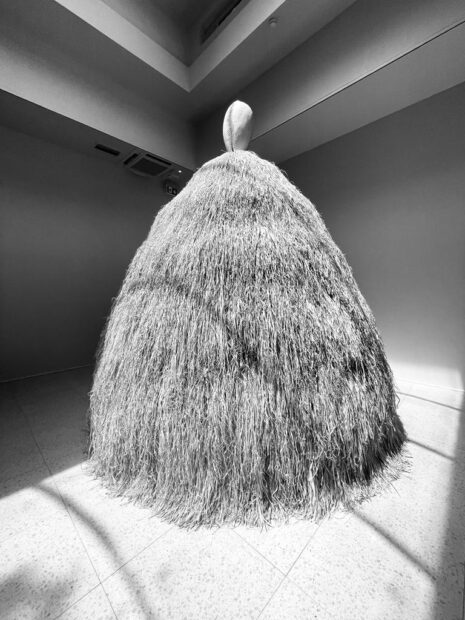

Simone Leigh’s work in the United States Pavilion. Photo by Pilar Goutas.

The main pavilion building looms like a modernist monolith, a nod to the purity of form and the ubiquity of the white cube. This year’s Biennale was titled and curated around the phrase “The Milk of Dreams.” Borrowed from the title of a children’s book written and illustrated by Leonora Carrington, a prolific female artist from Mexico often labeled as a surrealist painter, the phrase provides a conceptual entryway into the massive, winding journey of an exhibition featuring work by over 200 artists from the 19th century to the present day who represent more than 50 countries. More importantly, the included artists are all gender non-conforming and/or women.

The exhibition is overwhelming. It’s on the verge of being too much. And because it is mainly of women or gender non-conforming artists, I loved every second of it.

That is to say, I didn’t initially like all or the work or agree with many of the curatorial choices. But to walk through a large and impressive exhibition full of work made by women made me giddy. I wanted to high-five everyone there. It was a relief to be overwhelmed in this context — a “bring it on” moment, if you will. The deeper I got, as I wandered through the galleries, installations, and video pieces, accidentally bumping into folks in the crowd and hitting walls because of the lack of space, I realized I honestly had no complaints about any of it.

We constantly fight for representation and for our seat at the table, so to be in a moment where that fight was so visibly celebrated and given a voice was nothing but a relief. I walked out of the exhibition refreshed and ready to tackle the other surrounding pavilions. Unfortunately, the feeling didn’t last long, and fatigue very quickly set in.

Paolo Fantin, “Lympha,” installation view of the Italian Pavilion. Photo by Pilar Goutas.

This, however, wasn’t necessarily museum exhaustion or general tiredness from being on my feet; it was instead the sense of participating in a competition that revolves around nationalism. Think of EPCOT for art; for the most part it was just as flashy, flamboyant, and large. Enormous, actually. There is little intimacy in the exhibited works and the loose, underlying threads connecting one exhibition to the next are largely those of colonialism, representation, climate change, and violence. I just kept wondering who the intended audience was for this biennial and these pavilions.

To have an existential moment with this biennial as a whole is nearly impossible. It’s too big, too flashy, too full, and exhausting. Don’t misunderstand — I firmly believe the topics each show’s curator attempts to tackle are issues that need a larger platform. But wandering from pavilion to pavilion made me wonder if this type of spectacle just wasn’t for me. I felt like I had been repeatedly yelled at for hours, which, when coming out of a day of seeing art, is demoralizing at best.

I live in the current reality and consequence of the topics the exhibitions are addressing. I see the continuing legacy of colonialism (please stop moving to Mexico City); I have been the victim of petty violence (no, Mexico City is actually not safe); of colorism (yes, I am brown, I promise); and of representation (it’s not enough to have a seat at the table if your voice still isn’t heard, and please stop killing us).

Installation view of the Spanish Pavilion by Ignasi Aballí. Photo by Mike Counahan.

I wonder how effective physically enormous works can be in spaces that require massive amounts of money to build, and within a context of implied visual competition between countries. Sure, I understand we need to change our lifestyles to combat the ecological damage done by the baby boomers, but do I really need to see an enormous set of tree trunks penetrating the ceiling of a building? Why did I walk through a giant replica of an ear lobe in the Brazilian Pavilion? How were the enormous inflatable udders hanging from the ceiling of the Egyptian Pavilion in any way evocative of the female womb? Considering all of the ways it has suffered economically over the recent years, why was Venezuela there anyway, and wouldn’t its own population be a better place to invest its capital?

The Nordic/Sámi Pavilion. Photo by Mike Counahan.

Perhaps I am tired of the spectacle of these large, blockbuster art events. And given the number of people packing the gallery spaces in each pavilion, I can’t imagine every exhibition was made with each of them in mind either. It might be taboo to admit, but all art isn’t for everyone. Sometimes we, as visitors, have outgrown or moved beyond what the art is trying to say. In these cases, the art isn’t effective for us — a situation that tends to arise when artwork attempts to prescribe feelings rather than ask us to respond.

I left the Giardini and sat on a bench overlooking the bay. My eyes and my feet needed a rest. Even though I am a curator, I’m not ashamed to admit that spending a day looking at art zaps me. And exhibitions like those I had seen that day are especially taxing.

Simone Leigh’s work at the United States Pavilion. Photo by Pilar Goutas.

Every space in Venice is so large that one’s natural inclination is to fill it, a curatorial decision I can’t understand. I never feel pressure to fill a space for the simple sake of having space to fill. I also never feel inclined to compete with space, preferring instead to work in tandem with it and all the eccentricities it comes with. I want my audience to feel the work, the emotion; I want them to dig into it, get close to it, breathe on it.

We had packed up 28 works on paper by 25 artists into three suitcases in Mexico City and brought them to Venice. Each artist is a collaborator with Mike Counahan, a photographer resuscitating the heliogravure, a copper plate intaglio technique that combines elements of photography with printmaking and dates back to the early 19th century. We installed the work in an empty, diagonally oriented space with exposed brick walls, crumbling plaster, and piping; we could only drill into the mortar between the bricks — we had not seen the space before our arrival. There were challenges, but with any beautiful space comes a set of complications.

Installation view of “Helio: El Taller de Mike,” on view through November 29 in Venice.

I have known Mike for a long time. He has always been an artist who I have seen operate within his own time and world, a personality trait that somehow lends itself to the ancient technique he works in. His process gives the image some sort of something, which is hard to explain unless you’ve seen it. It’s a touch of softness and depth so dependent on light that it requires both time and patience.

Bringing the work of 25 artists together into one exhibition proved to be difficult. Every artist has their own distinct style and voice, but at the end of it all, the point of intersection is the process itself — the collaboration with Mike. So, I wrote a story about an artist who embarks on an adventure and traces the light through the landscape of Patagonia and the deserts of Bolivia, and who returns seeing the world through a new lens. Essentially, it is the story of an artist who becomes a stoic, and it happens to be the story of Mike.

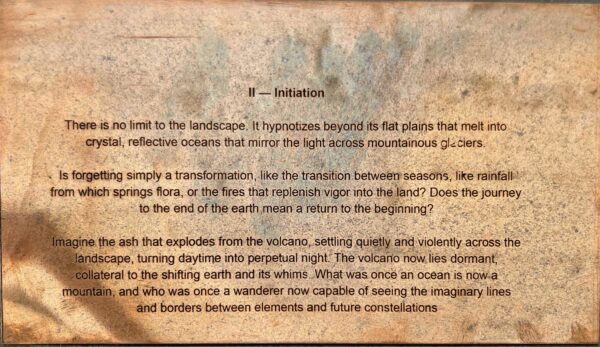

We printed the story onto copper plates and divided the work into the three conceptual parts of the metaphorical journey — Departure, Initiation, Return — and we’ve watched as the copper oxidized over time, aided by the humidity of Venice. It is my gift to Mike, and each section acts as a pause in the exhibition, like a comma. But we didn’t expect it to be a physical document of our time and our show in Venice.

Part 2 of 3 texts of a Stoic’s journey, oxidizing over time. Written by Leslie Moody Castro.

It is refreshing to curate such a small and intimate show about light and process. The Giardini is a spectacle, meaning it keeps its audience at arm’s length as countries vie for the most memorable installation decisions rather than working together with their spaces. We didn’t know our space before we arrived, so what has surprised us most is how the play of light in the physical space itself contributes to the idea of light conceptually in the work. The light changes everything, and it is different here. It is symbiotic with the humidity, with both elements becoming evident in the copper — absorbing both, oxidizing, changing, and reacting throughout our time here.

******

Thank you to every one of the artists involved in Helio: El Taller de Mike. Thank you to Mike for another opportunity to collaborate on a gorgeous project. To Luca, Elena, and Francesca of the Venice Art Factory, thank you for the incredible help and support on this very special exhibition, especially to your team of very patient installers. Thank you Alfredo and Memo in Mexico City for all the ways you prepared us to get to Venice and arrive with the work safe and sound. Eternal gratitude to Maripili for the foresight to capture this vision, and the trust you put into all of us.

And as always, thank you to our Glasstire team, for everything.