While a permanent collection show typically does not spark fireworks enough to make a special trip, the Modern Art Museum Fort Worth’s exhibition focusing on the institution’s last 20 years of acquisitions offers a fascinating glimpse into the sometimes opaque inner workings of collecting. Scholarship often seeks to elucidate the ways in which artworks reflect the period of creation, but equally important is how artworks respond to the time in which they were acquired into major public collections.

2002: Anselm Kiefer (German, born 1945), “Aschenblume,” 1983-97, oil, emulsion, acrylic paint, clay, ash, earth, and dried sunflower on canvas. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of The Burnett Foundation in honor on Michael Auping, 2002.17.A-D. © Anselm Kiefer

Although permanently on display, rather than recently installed for the exhibition, Anselm Kiefer’s Aschenblume provides a great entry point into the museum’s collecting history. This monumental work greets visitors as they enter into the main galleries on the first floor. Horizontally aligned, Kiefer transports viewers to the grand Mosaic Room in Berlin’s Reich Chancellery during the Nazi’s control of Germany. The artist provides a long view down the room, using linear details not only to create perspective, but also to hint at the architectural details of the space, such as ceiling windows and wall niches that contained mosaics. However, viewers’ encounter with this space is disrupted. Kiefer covered his canvas with ash, clay, and earth, alluding to the destruction of the government that created this structure. At the center of the painting, a long stalk extends vertically down the full length of the work, drawing your gaze downward. Blooming from the heavily textured base of the painting is a flower, a bright patch of white that’s strikingly clear in comparison to the muted grays and beiges that dominate the rest of the canvas.

Although Kiefer was already in the Modern’s collection, and efforts to collect additional works by the artist were likely underway well before September 11, 2001, the timely feel of this acquisition must be acknowledged. Reflecting back on 2002, in the immediate aftermath of September 11 and truly the start of a new chapter of life in the United States, this stark image would have had clear resonance with the television images circulating of the World Trade Center. Aschenblume offers Kiefer’s reflection on the transformation and hope of the new chapter that followed the widespread devastation of Germany during World War II. The introduction of this specific work into the museum’s collection in 2002 invites reflection on the resilience of the nation despite the great anxiety collectively experienced that year as the United States embarked on military conflicts that would shape new passages in the country’s history.

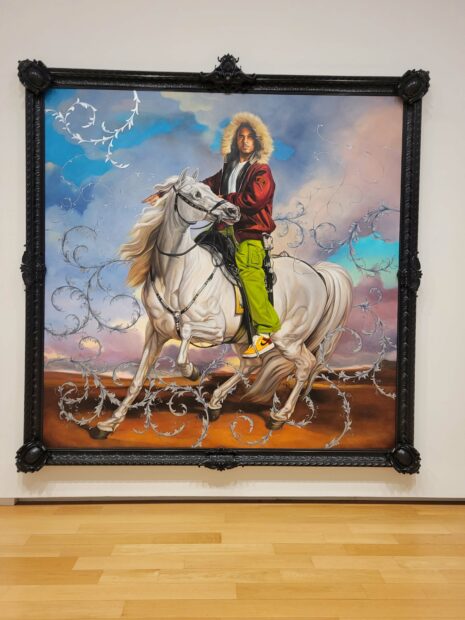

2008: Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), “Colonel Platoff on his Charger,” 2007-08, oil on canvas. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Gift of the Director’s Council and Museum purchase, 2008.2. © Kehinde Wiley

Hope and change. This was the motto and desire of many in 2008, regardless of political affiliation, considering the looming financial crisis. The candidacy and election of Barack Obama highlighted how far the nation had advanced following the Civil Rights Movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, perhaps towards an era of post-racial society. Yet there was also a recognition of the ways in which people of color had been marginalized in the country’s many institutions, including museums. The acquisition of Kehinde Wiley’s Colonel Platoff on his Charger illustrates the Modern’s willingness to engage with this problematic collecting strategy in a direct manner.

In this large-scale portrait, which references a historical image of a Russian military leader, Wiley deftly intervenes in the art historical canon using his signature style. The white male military hero expected astride the powerful white horse has been replaced with a young African American man dressed in contemporary street style: the sitter wears a brick red jacket with fur trimmed hood covering his head, loose cargo pants in a vibrant green, and yellow Nikes. Ornate silvery-white foliage swirls up from the frame to encircle him and his steed. Here, the Black male serves as commander, gesturing to viewers the path to take. The symbolism of this is not lost, considering that in 2008, when this work was added to the collection, the reality of an African-American Commander-in-Chief was becoming a real possibility.

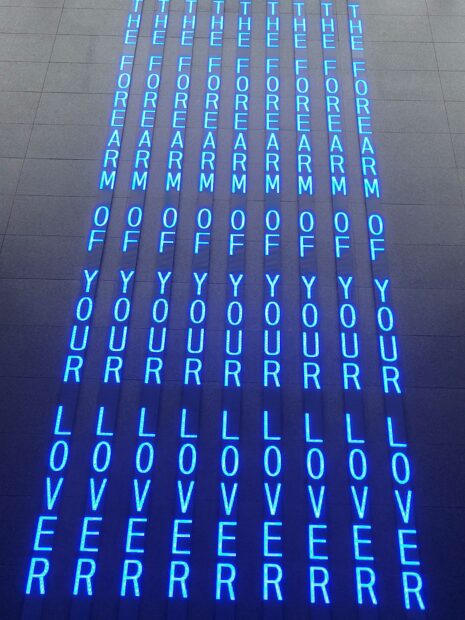

2012: Jenny Holzer (American, born 1950), “Kind of Blue,” 2012, 9 LED signs with blue diodes. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Museum purchase, 2012.3. © 2012 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Another perennial favorite of visitors to the Modern deserves another view. Installed on the museum’s lower level, Jenny Holzer’s Kind of Blue consists of nine narrow LED boards that extend the full length of a gallery to windows that open onto the museum’s courtyard pond. The screens are programmed with twelve hours of Holzer’s textual work, a compilation of short statements that exemplify the power of language and how meaning is created and shared in society.

In the eight years leading up to the acquisition of this work, the United States fully entered the social media age and people became accustomed to a constant stream of information, much of it short bursts of content with limited context. In a culture where readers are quick to scroll, this work invites one to linger, with curt and at times disturbing messages confronting viewers. The lack of authorial presence in the work also proves challenging; there is no clear speaker or physical body within the work to push back against. In many ways, this disembodied source of knowledge foreshadows the coming of misinformation perpetuated by unknown sources in a digital era.

The stream of blue text across the LED panels is also instantly reminiscent of contemporary stock ticker tapes. While the Great Recession, by official standards, concluded in 2009, the financial devastation it brought still reverberated in 2012 when this work was acquired. The election of 2012 resurfaced collective concerns about the unchecked power of large institutions (both government and financial) that prioritized their own benefit above the interests of the people. Holzer’s artistic investigations of power and control over narrative through language was a needed area of engagement in 2012.

2020: Shirin Neshat (Iranian, born 1957), Untitled (from Women of Allah series), 1995, laser-exposed gelatin silver print. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, The Friends of Art Endowment Fund, 2020.11. © Shirin Neshat

Shirin Neshat’s piercing self-portrait launches viewers into the present day, though the work was created in the 1990s. Untitled (from Women of Allah series) presents Neshat dressed in a long, solid black gown with matching head covering, a garment with strong associations to conservative Muslim cultures. While the black gown typically is seen as a barrier, protecting the female body from the male gaze, the portrait is strikingly open. Neshat’s body frontally faces the viewer with her hands and slightly bared right wrist extended as they sturdily rest on her lap. The brightness of her face is accentuated against her dark clothing by the placement of a leafy garland wrapping upwards from her chest and around the crown of her head. The powerful posing of Neshat is disparate from the artificiality of the garden backdrop.

While much has been said about the feminist issues explored in Neshat’s Women of Allah series, Neshat resists efforts to tidily label her work. It is worth noting, however, that these interpretations might have made this piece more attractive to institutions in a politically heightened year like 2020, during which there was great attention on how the choices of United States voters would impact women’s rights domestically and abroad. The U.S.’ war in Afghanistan did not reach its final conclusion until 2021, but the drawing back of coalition efforts renewed debates over the West’s role in supporting women in countries with ultra-conservative religious governments. Yet, one would be amiss to not acknowledge the nostalgia Neshat’s work evokes. The confinement of quarantine left many longing for the opportunity to safely leave their homes. Open spaces like parks and gardens were a desperately needed refuge, but some were resigned to only enjoy lush landscapes in the form of Zoom backgrounds.

There are many other major acquisitions on view in this show, all worthy of deep and critical reflection. It is important to remain cognizant of the power given to institutions, including museums, to shape the historical narrative. Beyond a fun journey down memory lane, exhibitions like Recent Acquisitions 2002-2022 provide visitors a moment to interrogate what is being added to that narrative for future generations. It is important for visitors to engage with museum’s permanent holdings and assess whether (and how) our institutions are reflecting and responding to the communities they serve.

Recent Acquisitions 2002-2022 runs through April 24, 2022 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Ed. note: Since our writer’s visit to The Modern, Anselm Kiefer’s Aschenblume has been deinstalled. A different piece by Kiefer, Papst Alexander VI: Die goldene Bulle (Pope Alexander VI: The Golden Bull), is currently on view in the museum’s lobby.