Robert Rauschenberg, Accident, 1963. Lithograph from two stones, 41 x 29 in., edition of 29. Published by Universal Limited Art Editions, printed by Robert Blackburn and Zigmunds Priede

American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s famous piece, Accident (1963), is aptly named.

During proofing — a stage of printmaking where an impression of the image is taken — the lithographic stone Rauschenberg was working with broke. Rather than try to refit or repair the stone matrix to try to create a seamless surface, Rauschenberg embraced the break as it emphasized the physical, dynamic, and social elements of the printmaking genre. Accident went on to win a plethora of prizes for printmaking (including first prize at the prestigious Ljubljana Graphic Biennial in 1963) and was quickly established as one of the twentieth century’s most iconic graphic works.

In his new book Prints and Their Makers, master printer Phil Sanders points out that this traditional telling overlooks the fuller story of Accident — the story of Rauschenberg’s collaboration with with Robert Blackburn, a prominent American Black artist, printmaker, and MacArthur recipient who founded a cooperative print studio in New York City in 1948 and became the master printer at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) in 1957. Created and printed at ULAE under Blackburn’s watch, Accident emphasizes that printmaking is a collaborative, social medium that depends on combined expertise to create and execute the work. The success of Accident may have depended on happenstance, but the circumstances of its creation were anything but haphazard.

“Printmaking could incorporate the call and response of painting, the physical approach of working a drawing, and the sculptural mindset of combining and recombining elements,” Sanders explains in his new book Prints and Their Makers, published by Princeton Architectural Press. “It lives at the intersection of these more ubiquitous media, drawing from each.”

Marie Watt, Companion Species (What’s Going On), 2017. Four-color woodcut from four separate artist-carved shina plywood blocks, 17.5 x 18.5 in., edition of 14, published by and printed at Crow’s Shadow Press, printed by Frank Janzen, assisted by Judith Baumann

Prints and Their Makers connects the world of contemporary printmaking with the historical techniques and technologies that that have developed over centuries. Specifically, Sanders focuses on seven major printmaking processes: relief, intaglio, chine collé, photogravure, lithography, monotype and monoprint, and screenprint. Sanders delves into the mechanical details of each, walking readers through how print is created and how every historically new technique depended on its precedent’s use of different papers and inks as well as press technologies.

For example, Sanders grounds his opening discussion of European relief printing with Albrecht Dürer’s famous early sixteenth-century woodcuts, and quickly moves the discussion to artistic communities around the globe that in subsequent centuries built technique on relief printing.

The point about the continuity of relief printing is well made by Sanders’ juxtaposition of Dürer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and a 2018 work by contemporary artist, Christiane Baumgartner, titled Silver on the Horizon. Although the similarities in lines and spaces are unmistakable, Baumgartner’s piece draws audiences’ focus to the bright, white space that we assume is the sun either rising or setting on the horizon. Other examples from the discussion of relief printing include works by José Guadalupe Posada, Katsushika Hokusai, Jost Amman, among others. “After more than 1,350 years of relief printing, artists are still finding new ways to vary a line, new ways to draw, and new creative wells to draw from,” Sanders summarizes.

Prints and Their Makers started as a series of videos that Sanders created to explain the printmaking process and accompany a 2011 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. (I took a detour through the YouTube series and the short videos are a perfect complement to the printed book.) Once uploaded, they took on a life of their own and the process of turning the videos into print — turning them into Prints and Their Makers — feels like a perfect manifestation of print’s materiality.

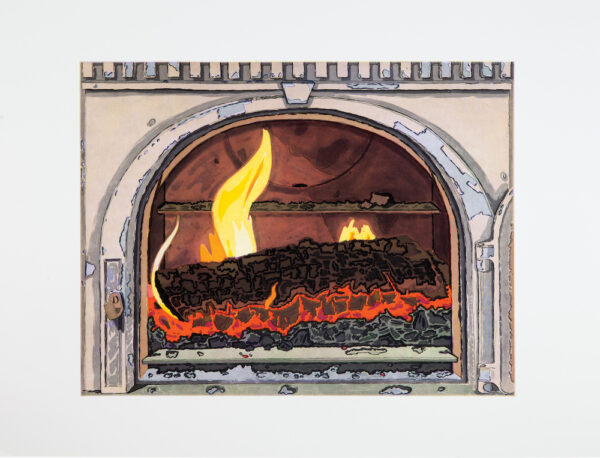

Josephine Halvorson, Fire, 2019. Five-plate aquatint etching with drypoint, soft ground, spit-bite, and sugar-lift, 25.5 x 29 in., edition of 20, published by and printed at Wingate Studio, printed by Peter Pettengill and James Pettengill

For over a millennia, printmaking has been the art and technology of creating copies —creating copies and generating the social means to put those reproductions into cultural circulation. Prior to print, texts and images had to be individually reproduced; print offered a means to machinate inked paper en masse. Historically, Gutenberg and his printing press are credited with the sudden popularity and possibility of print, but the press is only one element of a complex ecosystem of print. As paper, ink, and plates have morphed throughout the centuries, the possibilities and social roles of print changed as well. Thus, what we call “print” is really hundreds of decisions about paper, ink, and how to combine them.

Tom McGrath, Untitled, 2015. Photogravure and sugar-lift, 15 x 21 in., edition of 9, published by and printed at Flying Horse Editions-UCF, printed by Adrian Gonzalez

“Traditionally, artists have used printmaking as a way to reproduce their work in their primary media,” Sanders points out. “However, replicating the world as it exists is certainly not the limit of printmaking’s potential… . The history of print is a living history.”

Jules de Balincourt Merging Islands, 2016. Eight-color lithograph printed fromeight stones, 27 x 32.9 in., edition of 60, published by and printed at Edition Copenhagen, printed by Rasmus Urwald, Peer Carstensen, and Henning Johnsen

It’s impossible to summarize the wellspring of history and technical details that Sanders offers in Prints and Their Makers, but the most evocative, consistent theme to run through the work is the collaborative aspect of printmaking. And it’s putting that “material literacy” — as Sanders calls it — into play that artists and printmakers depend on to create and circulate prints, whether en masse or not. The final chapter that shows the sheer variety of vivacious contemporary prints — like Ellen Gallager’s DeLux (2004/2005); Sarah Crowner’s Untitled (spotlights B) (2013); and Chitra Ganesh’s The Fortuneteller (2014) — emphasizes that printmaking is a dynamic, animated, contemporary genre that owes a huge debt to its own history.

“The invention of printing is the greatest event in history,” Victor Hugo claimed in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. “Printed thoughts are everlasting, provided with wings, intangible and indestructible.” Hugo is referring, of course, to centuries of printed text. But it’s impossible to not see printed images as claiming a similar sort of social space, presence, and resonance.

Find Phil Sanders’ Prints and Their Makers here.

1 comment

Fascinating insights on printmaking – looks like a book to add to ones library!