Fascination with color goes way back in our evolutionary history.

From paintings at Paleolithic sites like the famous Lascaux and Altamira caves in Europe to painted figures from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, Homo sapiens have long been captivated with how color and material come together to form art. (Indeed, interest in the aesthetic properties of color isn’t limited to our species; 200,000-250,000 years ago Neanderthals used colored pigments in a plethora of abstract ways.) Fast forward tens of thousands of years, and humans are still turning over the question and meaning of color.

A formal history and theory of color will, inevitably, borrow heavily from natural history and physics. It should include philosophers from antiquity, like Aristotle, Isaac Newton’s theory of optics, and perhaps even Johannes Wolfgang von Goethe’s theory of color. While this sort of approach to color theory tells us how color is seen, how color works, and even, at its most existential, what color is, it neither tells us what to do with color nor celebrates the ways that color writ large intersects the human experience.

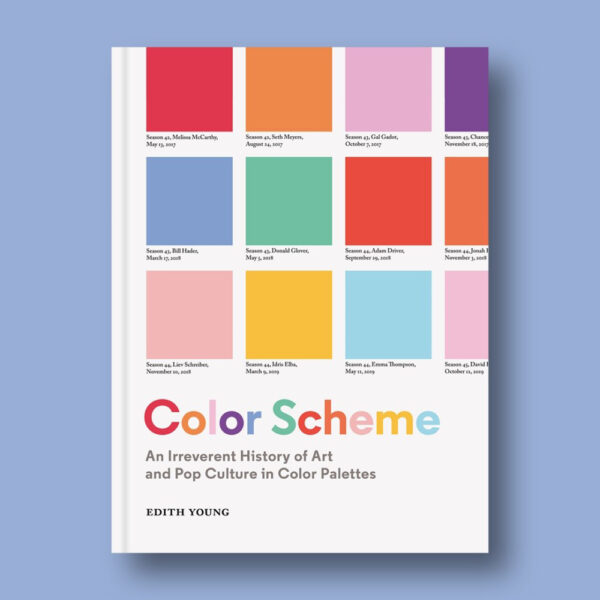

Color Scheme: An Irreverent History of Art and Pop Culture in Color Palettes by Edith Young, however, explores those precise themes. Color Scheme is a brilliant, smart examination of how we think about color, how material medium informs color, and how these ideas have changed over time. Broken into three sections — Art History, Contemporary Art, and Pop Culture — Color Scheme uses a plethora of carefully curated, neatly tiled color palettes to highlight the lifespan of a specific theme, object, or material.

“While these palettes can be enjoyed for the colors alone, the ongoing research project is committed to showing viewers new ways of thinking about artists’ oeuvres and larger arcs in art history,” Young writes in the introduction. “No matter how much you know, I also hope this book might serve as a conduit to discovering new artists or new elements of work you’re already familiar with.”

Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582 / 83–1666), Anna van der Aar (born 1576 / 77, died after 1626), 1626; oil on wood. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

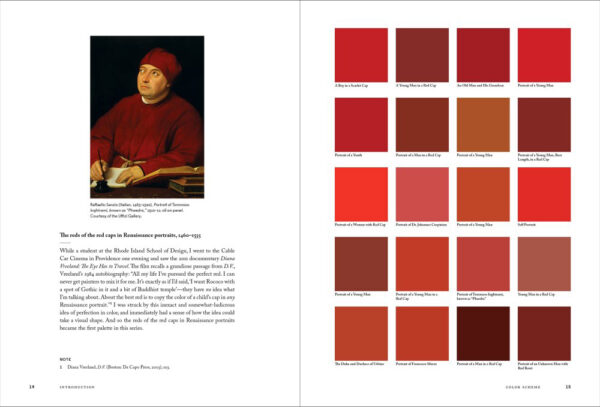

Young’s approach encourages audiences to think about color as it appears in its used, material medium. Historical examples of palettes Young has compiled include the dresses worn by infantas Diego Velázquez painted over his career (oranges, taupes, grays, and a blue). The ways in which hues of black, brown, and green are combined offer sixteen distinct colors of pupils in Johannes Vermeer’s subjects. (The pupils of a Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace (1662–1664), for example, are much more brown than those of Girl With A Pearl Earring (1665.)) The reds of the red caps in Renaissance portraits — one of which Young credits with igniting her interest in this project — join the palette of ecus, lavender, and beiges in Dutch painter Frans Hals’s portraited ruff colors.

Young’s approach to laying out colors is particularly effective because when we see the painting that one palette tile comes from (one red Renaissance cap, for example), we see the tiles together as a collected set, and then we can imagine them back in the original work. It’s as through each featured color has been deconstructed and then reconstructed. For example, I found myself “matching” the color of Hal’s Anna van der Aar’s ruff collar (1626) with its palette tile and wondering why the artist chose that specific white when there were so many other colors that nearly matched.

Robert Havell Jr., (British, 1793–1878), after John James Audubon (American, born Haiti, 1785–1851), White Headed Eagle, 19th century; hand-colored engraving, etching and aquatint. Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop.

I felt the same wonder and awe at seeing the book’s illustrations of the blue bird bills from Joan James Audubon’s The Birds of America — it was a catalog of color. Color Scheme is, in a way, reminiscent of nineteenth-century natural historians’ work to document their observations as records; this “sciencizing” of color is reiterated by the CYK descriptions of every example in the book’s endnotes. After spending time with Young’s palettes, I can guarantee that I will never again look at a ruff collar or Audubon bird bill the same way.

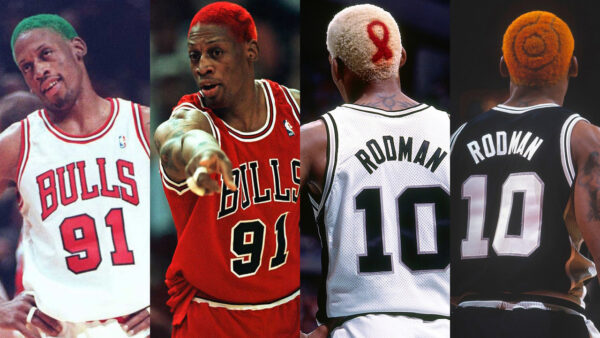

But Young does not restrict her palettes to long-historical examples. She widens the scope to include work by contemporary artists, like Helen Frankenthaler. She also shows how colors carry cachet and influence in pop culture. To this end, Young includes a palette of Tanya Harding’s figure skating costumes by competition; Prince’s concert outfits; how Pete Davidson dresses from the waist up on Weekend Update for Saturday Night Live; and even Spike Lee’s eyeglasses from 1989-2020. There’s a two-page spread of Dennis Rodman’s hair dye, in chronological order over the course of his NBA career (“I consider Dennis Rodman to be one of the great colorists of our time,” Young states.) Each palette is its own historical moment of collecting, cataloging, and considering.

Color Scheme is short, pithy, and fundamentally challenges how readers think about and internalize the colors that surround them.

Edith Young’s Color Scheme: An Irreverent History of Art and Pop Culture in Color Palettes was released on November 2, 2021 by Princeton Architectural Press and is available here.