Can you teach someone how to read a book of photographs? Unlike most other very niche types of books, they are not one type of book. Nothing about them is streamlined from title to title. While some leverage visual juxtaposition for “narrative” thrust, others act as buckets for someone’s favorite pictures. Still others present like a single folder out of a filing cabinet, the one marked “those folks over there” or “that type of building.”

Are books of photographs more like gallery exhibitions than they are novels? Maybe sometimes. Then again, maybe not. A book is a thing made mostly of glue and printing costs. It is more fixed and definite than a room full of framed pictures, which can be jumbled up whenever, however. It is exactly this, a photography book’s potential to present formal surprises within the modest and permanent framework of its covers, that makes the genre a ton of fun and titles, potentially, worth like fifty dollars.

I find this process of writing about these books to be a nonstop series of tiny adjustments. Take right now: I lay on my couch and put on a 27-minute instrumental track by The Cure, something from a film soundtrack. Then I pick up a book and what? Skim? Flip around? Study each individual film grain in a single plate? The quiet job of each book is to teach me how to read it. Maybe I’m just in a state at the moment, but after a day spent doing whatever else I do, it’s enough to make me feel rather dumb. That’s okay; a good reminder.

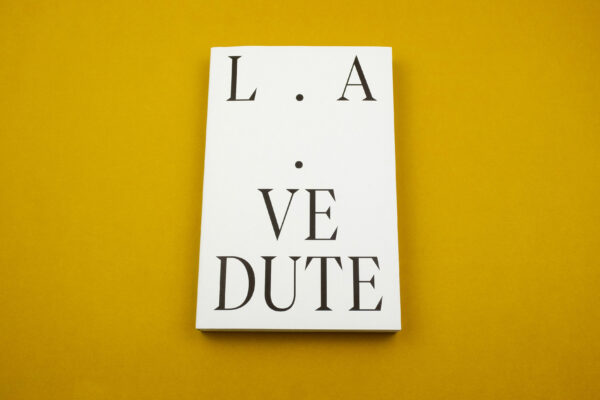

As an apparently stupid person, I just spent around six minutes on my computer trying to decode the phrase “VE DUTE” as it appears on the cover of Thomas Locke Hobbs’ magnetic recent book of black-and-white Los Angeles streetscapes. Far as I could tell, the phrase was Romanian for “they will take you.” Ominous. A threat, in reference to the depicted landscape’s utter lack of people? No, utter nonsense.

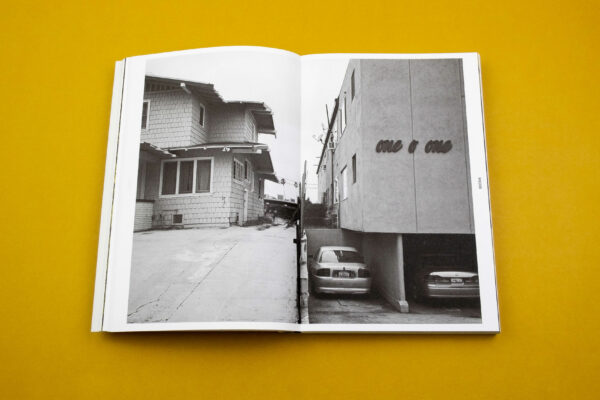

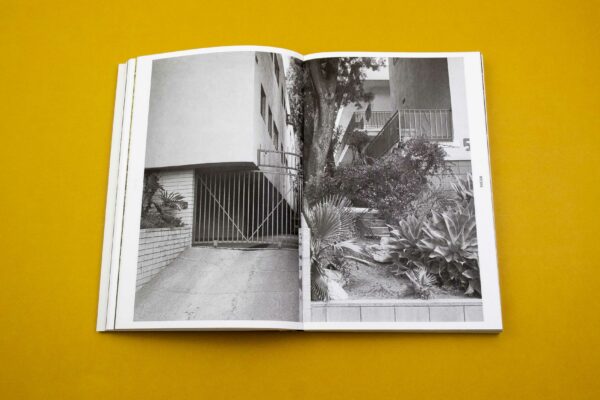

A quick glance at the book’s title page reminded me that the book is actually called L.A. Vedute, Italian for “views” and a nod to some landscape pictures made by Piranesi and others way back when. The cover just has a clever design, maybe in reference to the persistent “split” that happens in the photographs. When you get down to it, there is something a little Piranesian about them.

L.A. Vedute by Thomas Locke Hobbs. Published by The Eriskay Connection, 2022. Find the book here.

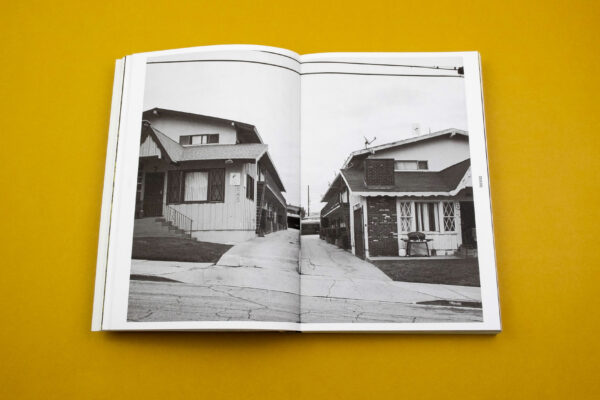

The thing about the pictures is they’re beautiful, and it’s complicated. In that way they’re like the place itself. I have strong teenage memories of crawling through traffic along I-10 into Los Angeles and dumping awestruck missives about the skyline into my little notebook. Asphalt, concrete, and steel, twisting illogically to the whims of who knows how many developers. Beautiful.

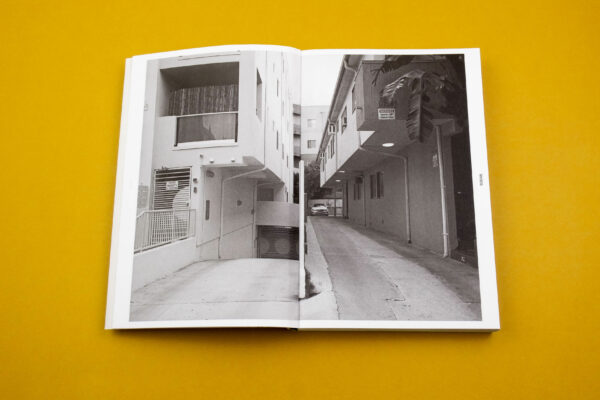

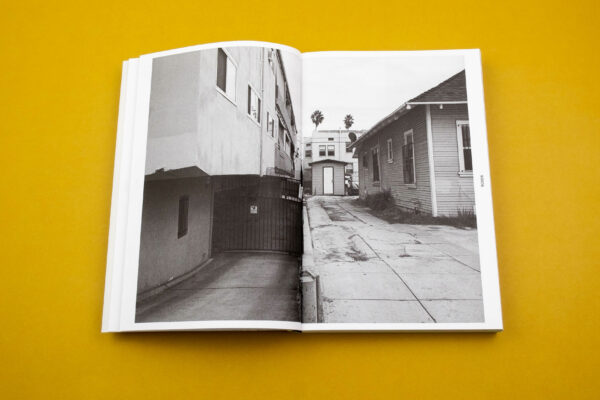

In an email exchange shared near the center of this book, the photographer Thomas Locke Hobbs tells eminent photo world guy David Campany that Los Angeles is a “contemporary dystopia.” That view comes as a mild surprise, because while the pictures are technically systematic they are also, at first glance, affectionate. Hobbs photographed negative spaces with devotion. He fixed a large-format camera on the vanishing points between Angeleno residencies, with driveways, carports, and entryway gates as focal points. But the book lets these pictures bleed across two-page spreads, and the focal points are more or less eradicated as they sink into the gutter. What’s left to see is a chaos of angles in large format detail, the many edges of residential architecture and its haphazard foliage. It is an antithesis to Ed Ruscha, a heart in the same Google Street View robot that contains Ed’s brain.

The pictures pace on in this way, piece by piece, constructing a complex description of Los Angeles without ever focusing on anything in particular. Hobbs, in his correspondence with Campany, comes off more critical of these spaces than the photographs betray: “Absent is any sense of conscious design or civic culture at play. The separation between two buildings, which is mandated by law to enforce a false suburban ideal, creates an involuntary, shared space which resembles something communal but which is not used or even recognized as such.” He and Campany even throw around the downfall of civilization, “a last moment before imminent collapse.” I don’t know. It is possible that an apocalyptic vision requires tenderness. Or maybe the affection that I sense in the pictures is actually coming from me, a viewer hypnotized once again by the odd vernacular geometry of L.A.

****

Vacation Pictures by Matt Price. Published by Golden Hour Publishing, 2022. Find the book here.

Speaking of Los Angeles, that’s where Matt Price lives. But Vacation Pictures does exactly what it says on the tin. Price is a skateboard photographer by trade, a job which sends him all over the world to document kids who jump off buildings for fun and profit. These are pictures from those trips, and while skateboarding is barely depicted, its presence felt throughout the book.

The whole thing pulses with a persistent sense of joy. You can almost smell it. And why not? Here are a bunch of apparently healthy young men living not like rock stars, nor like neo-Beats, but with lives adjacent to those things though perhaps much stranger. Take the photo of a man with his eyes closed, standing alone in what appears to be the empty expanse of West Texas, lunging forward to closed-fist punch a beer bottle that just happens to be flying through the air in front of him. What?

It was put to me once by my therapist that skateboarding is an ideal activity for maladjusted, socially anxious youths. It makes sense when you think about it: It is a physically demanding athletic pursuit that often puts you in close proximity to like-minded folks, while at the same time allowing you to spend the majority of your day staring at your own feet. Vacation Pictures makes a case for the opposite, or at least suggests that skateboarding might create a path through social anxiety and into fraternity. Fit, shirtless men cheese for the camera while cleaning each other’s underarms with a mop. Someone backflips off a car while onlookers beam from a small, crowded stoop. There is even an action shot of a high-five.

“The Widelux is the coolest camera I’ve ever owned,” begins Price in the book’s short introduction, setting the tone for the whole project. I don’t care about cameras, but I’m glad Price likes his so much. My favorite thing about Vacation Pictures is how obviously the photographer made this stuff because he actually enjoys it. He loves these folks, this life. It’s a bewilderingly rare sentiment to find in print, and it is good.