Across the 1970s, the filmmaker Hollis Frampton wrote a series of black-hole-dense essays on photography for Artforum. These pieces led him on quite the journey of the mind, a path that traversed ideas from Eadweard Muybridge’s dalliance into homicide as potential inspiration for his photographic studies to a 1000-foot metal sphere that was dredged up from the ocean and breached by a team made of a photographer, a psychiatrist, a mountaineer, and a “small contingent of heavily armed Commandos.” Depending on who you ask, it’s either some of the best stuff ever written about the medium, or a lot of hot air. Most likely whoever you ask will simply respond, “wait who?” For me, it simply rocks; I wouldn’t be here without it. If you’ve known me long, you know I’ve already gone on about Frampton for way too long. But:

One image that keeps popping into Frampton’s consciousness throughout the essays is a semi-hypothetical, near-infinite archive of photographs. The aforementioned expeditionary force, which appears in Digressions on the Photographic Agony (1972), emerges from the oceanic sphere “[d]azed, grimy, their faces frozen in the hornswoggled look of men lost in a perfect ecstasy of boredom, they explain that they have found… nothing. Or, rather, less than nothing: they have found only photographs” (emphasis original). Turns out, they’ve happened into a version of the Lost City of Atlantis that was built exclusively to be photographed. Once the pictures were taken, the Atlantians dismantled the city and left behind only the photos and “a critical tradition to accompany the images: a puzzling collection of writings that is gathered into the so-called Atlantic Codex.” In the story, an entire field of academia is developed to decode this text.

Two years after Digressions, at the beginning of his most useful essay, Incisions In History/Segments of Eternity (1974), Frampton puts the idea of the pile into the mind of a “tall young woman at an imaginary party.” Midway into their conversation, Frampton presses her — a historian and figment of the author’s imagination — to expand upon her answer to his ridiculous question, something like “what is history?” Because she is actually Frampton, she goes on and on, at one point “confiding”:

Now I hope you won’t think me vulgar… but it seems to me that nowadays both the ash-heap and the file of photographs are constantly expanding. I suspect, even, that there is some secret principle of occult balance, of internal agreement, between the two masses of stuff. The photographs are all splendidly organized according to date, location, author and subject; the ash-heap is perfectly degenerate. Both are mute, and refuse to illuminate one another. Rather, pictures and rubbish seem to conspire toward mutual maintenance; they even increase, in spite of every human effort. Just between you and me, it won’t be long before they gobble up everything else.

Whenever Frampton’s mountain of pictures surfaces, it presents some sort of obstacle; a physical and intellectual entity that photographers, academics, and even time itself are forced to contend with. And yes, it’s always been a tricky medium. From Digressions: “The instantaneous mnemonic process works with perfect precision, no matter who presses the button. In every early discussion of photography as an art, it is that single fact that seems to cause the most trouble.” Hollis Frampton died young, sadly, from cancer, in 1984. How much has the file of photographs expanded since then? What about the ash-heap? What now?

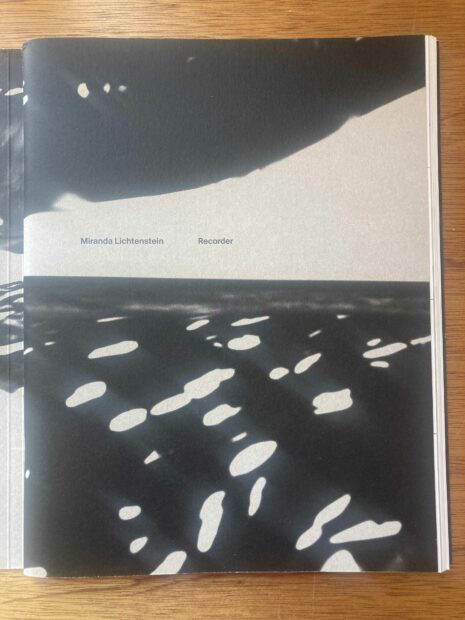

Recorder by Miranda Lichtenstein

Miranda Lichtenstein’s photographs are not, at first glance, the type of pictures one might expect to be published in book form. Actually, at first glance they aren’t even photographs. But Recorder is the photography book that once again got me thinking about Frampton and his ash-heap. Quoted in a Prudence Peiffer essay at the back of the book, Lichtenstein asks an ominous question: “Why take another picture?” At one point or another, a similar sentiment of existential dread has permeated the thoughts of most photographers I know. They ever increase, in spite of every human effort. Liechtenstein, however, took it to heart. Motivated by her own disillusionment with taking pictures — “I was no longer interested in what I could do or say with the medium out in the street” — she set about “cannibalizing” her personal archive. Old photos become source material for this collection of wildly muddled, non-representational pictures.

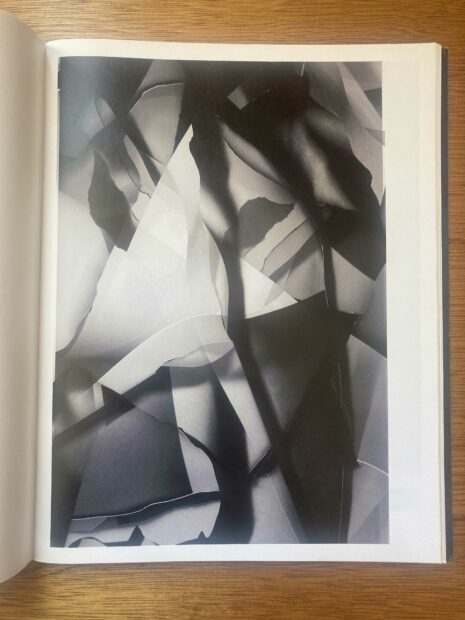

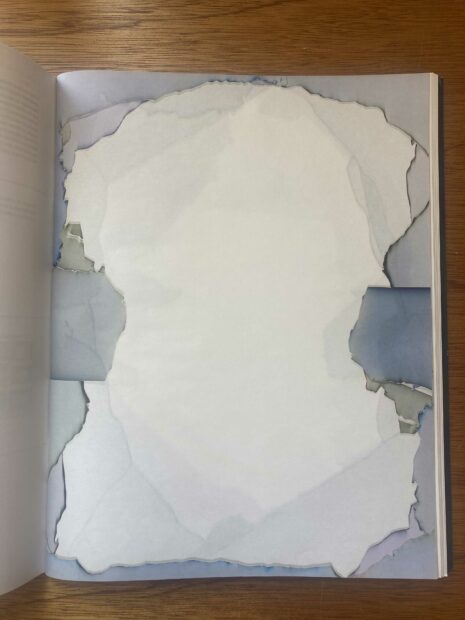

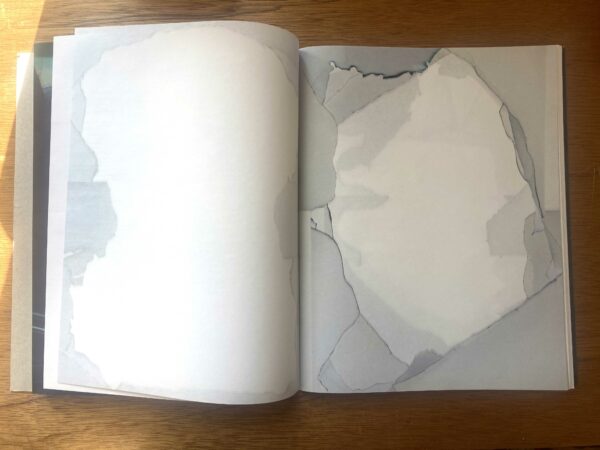

Except they aren’t entirely non-representational. While the original content of each photograph has been fervently banished to the ash-heap, what’s left still very much depicts the medium. The standout series of works in the book, all titled Ground, are made from the torn scraps of countless photographic prints. The printed areas have been excised (in some ways an inverse of Frampton’s description of photographs as “incisions in history”), and the borders remain as jagged, island-like frames around big, vacant, solidly white expanses. They are in equal parts anxious and haunted. In the book these pieces were printed on much lighter weight paper than the other plates, and on single-sided pages. The ghost image of each Ground, white void fading even further toward total white, shows up on the verso.

The presence of white in photographs does not indicate nothing. That honor belongs to black. If no light touches a piece of film, that negative developed and printed will yield an entirely black print. The same thing happens if you leave your lens cap on your mirrorless Sony. A completely white photograph is the result of the opposite: too much light has passed through the lens. It’s fundamental. So the old scraps of photographs, the frames around the what-used-to-be-theres that were obliterated in order to make these Grounds, now surround everything.

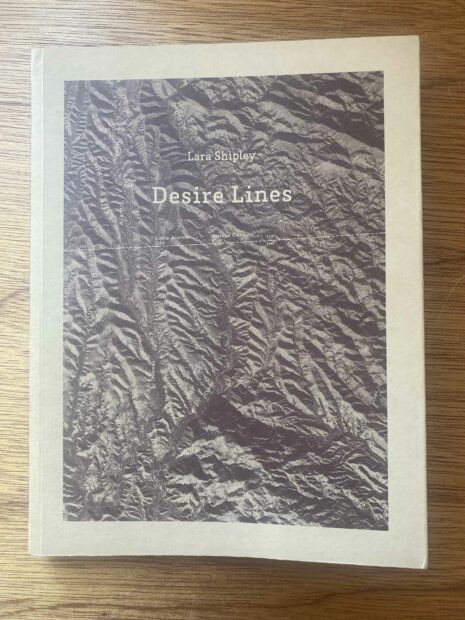

Desire Lines by Lara Shipley

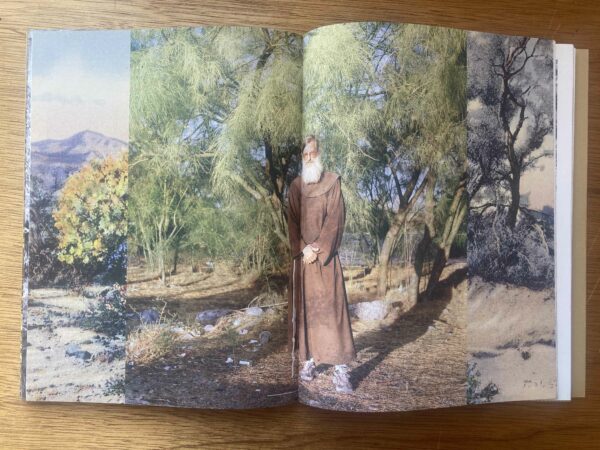

To avoid burying the lede, let me first say that the novel-shaped Desire Lines provides the most human, nuanced, and accurately complex depiction of life in the U.S.-Mexico border region of the Sonoran Desert that I’ve ever encountered in a group of pictures. Somehow, the photographs also manage to acknowledge the overwhelming beauty of this harsh terrain. This writer, who was born in that desert, is happy about it.

But now a disclosure: There’s a jpeg in some long-dormant Facebook file of photographs that depicts younger versions of Lara Shipley and myself sitting next to our mutual professor, Bill Jenkins, as he prepares to discuss Hollis Frampton with us and the rest of our class. It was around that time, as a graduate student at Arizona State University, that she started making the work that would end up in Desire Lines.

Shipley and I haven’t been in touch much since those days, because of life, but I’ve continued to follow her work. When she contacted me to say she had a new book out, I was already thinking about Lichtenstein’s Recorder in terms of Frampton’s writings. I did not expect to be able to fold Desire Lines in alongside it, but it wound up being a perfect foil: Shipley’s own relationship to the infinite-photo-producing-machine is clearly felt within the pages of her most recent publication.

Interspersed with her own photographs are a collection of historical images. These are mostly of “Wild West”-type stuff: hard white men with wide hats and big guns; indigenous people digging a ditch. There is also a full-bleed reproduction of a postcard image I saw regularly as a kid in Arizona: a dweeb, a white male photographer in 1950s garb, stands in the archway created by a mighty, many-limbed saguaro cactus that has grown too large so that some of its appendages drape back down to the earth. The eager little tourist, unconcerned with the otherworldly majesty of the whole plant, is right up in there snapping an up-close picture, and maybe has a dozen cactus spines visible through his rangefinder. Taking pictures about taking pictures has been a thing for a while. It’s a charming, enduring image of the region. Over the bottom right corner, Shipley has superimposed a horrific photograph of a desiccated human corpse that looks like it had been abandoned somewhere out in the desert. The source of this second photograph is unclear.

Shipley makes the archive an asset. She brings frontier mythology into the present through sequencing; suddenly the cowboy fantasies are full of brutality and are no longer only myth. As she writes in an insightful essay near the back of the book, “things haven’t changed that much.” But the juxtaposition wouldn’t work if it wasn’t for the variety and coherence of her own photographs, which far outnumber the archival documents in the book.

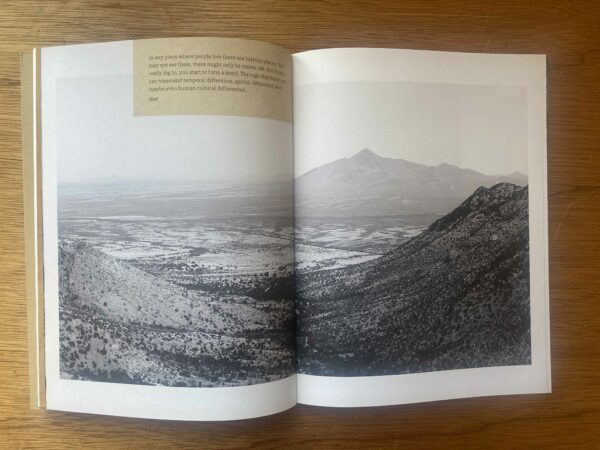

Everything out there is defined by the desert sun. We zoom out from portraits of folks shielding their eyes — made with a real collaborative quality that can be achingly rare in photo world documentation of American small-towners — and are all of a sudden looking across an endless expanse of creosote as an unseen vehicle kicks up clouds of dust from a dirt road. A man stands in the shadows of the border fence, which dwarf him as he seems to contemplate it. Caches of bottled water, left by some humanitarian for passing migrants, cluster around the bases of scrubby trees. It’s easy to miss the swooping chopper concealed behind the tips of an ocotillo.

Even pictures made at night seem informed by the sun; activity increases after it sets. In some pictures, Border Patrol aircraft, via long exposure, become light shows in the evening sky. Elsewhere, their spotlit checkpoints are the only things that escape the all-consuming black. There are double exposures, fragments, and pictures set inside others. Shipley, no tourist, leaves nothing on the table in her investigation of lives in the endless Sonoran. Anything less than that would have come up short.

Jonathan Williams’ copy of Two Blue Buckets by Peter Fraser

I’m headed somewhere else now.

In September in Sylva, a small mountain town in western North Carolina, I happened upon a bookstore that confoundingly shares its name with San Francisco’s famed City Lights Books. Tracking the origins of that parallelism would be its own investigation, and I doubt I’ll be back in the region too soon, so I will leave it aside as a curiosity. What matters now is that, as a bookstore, the southern City Lights holds its own.

One shelf in the back of the shop contained a well-labeled but picked-over selection of used books from the estate of Appalachian poet-publisher-photographer-polymath Jonathan Williams (1929-2008). The Black Mountain College-affiliated Williams was the founder of The Jargon Society, which published works by the likes of Buckminster Fuller, Mina Loy, and Kenneth Patchen. That imprint was also the first to reveal The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s singularly weird portfolio of hideously masked kin, to the general public. Williams was also a contributing editor for Aperture.

A lot of what was left on his shelf at Sylva’s City Lights was either too obscure for me or a book about cheese, although I do have evidence that Mr. Williams read David Ignatow’s New and Collected Poems while eating ketchup. Tucked in one corner I was delighted to find Two Blue Buckets, the Welsh Peter Fraser’s 1988 photo monograph, a book I’ve wanted for years. It cost me $25, more than it would have online and more than I wanted to spend, but the novelty of its former owner pulled me in. It’s got a smell.

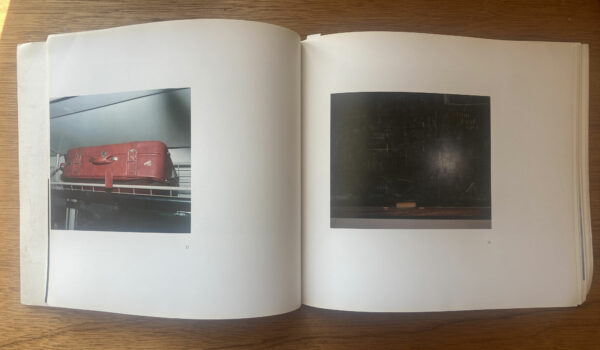

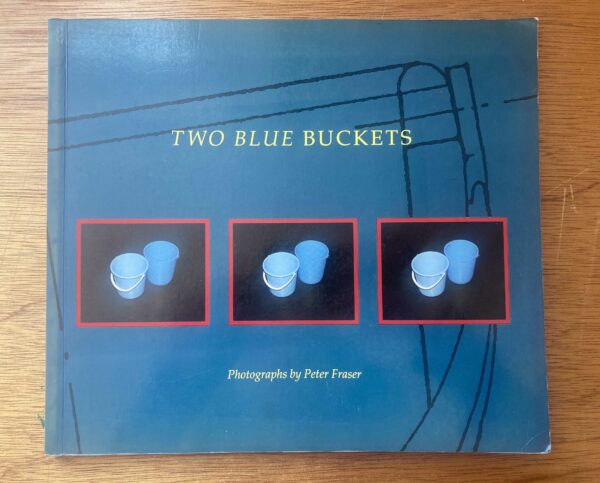

Peter Fraser’s (b. 1953) color compositions are intensely direct to the point where it’s nearly confusing. His work is not as encompassing as his predecessor and one-time co-conspirator William Eggleston’s, nor as ironic as that of his Gen-X analogues, like Jason Fulford. Two Blue Buckets is named for a photograph of two blue buckets, which appears in triplicate on the book’s cover and once inside the pages. The buckets sit side by side and… that’s pretty much it, aside from some out of focus tables and chairs that are suggested around the edges of the frame. Somehow, though, these are the most captivating two blue buckets anyone has ever seen fit to show anyone.

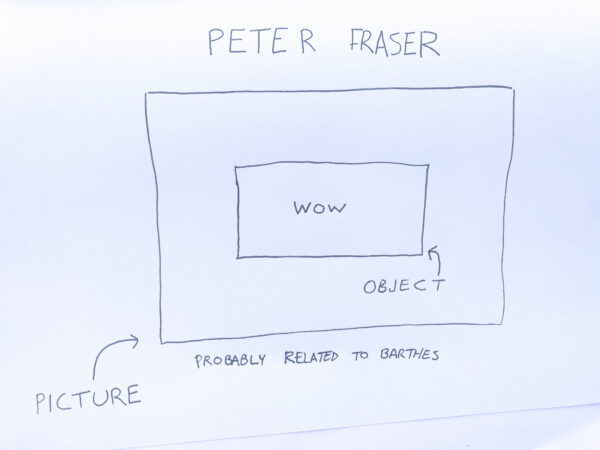

The same thing happens over and over throughout the book. A red briefcase on a luggage rack, a folded-up wheelchair, a board spanning the six-foot gap between two more (white, upturned) buckets. Fraser’s deadpan turns all these objects into sculptures. I have another one of his books, a self-titled thing from 2004, and I’ve long struggled to find the words for why any of his pictures work as well as they do. Here’s a recent diagram that I showed in a lecture while trying to figure it out:

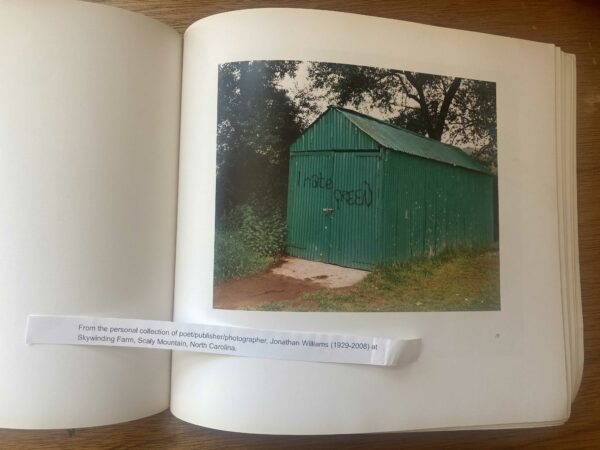

With my critical thinking skills failing as if Fraser’s pictures spring up from the page and smack me right in the face whenever I look at them, let me instead say something about this copy of the book. The only proof I have that it once belonged to Jonathan Williams is a small slip of paper that City Lights stuck into all his books that reads, “From the personal collection of poet/publisher/photographer, Jonathan Williams (1929-2008) at Skywinding Farm, Scaly Mountain, North Carolina.” So they could have faked it. But Williams is a relatively niche figure, and everyone at the shop was friendly. I think I’m safe there. Still, there is no real record of provenance; no signature, no bookplate. I gain nothing tangible from owning this copy over the $19 one on AbeBooks.

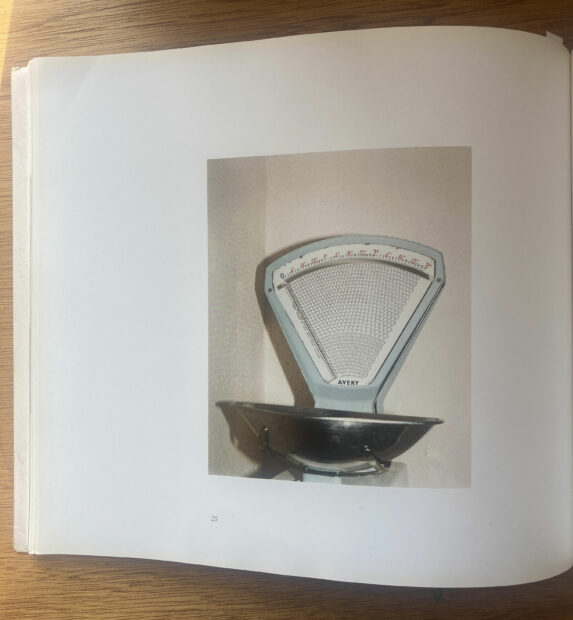

What I do receive for my $6 surcharge is a flimsy, but palpable, conduit to the past. A book has a history. It is fun to imagine the guy who wrote this poem flipping through Fraser’s book and meditating on his picture of an Avery scale. The scale seems to contain and weigh what describes it: a blast of light from Fraser’s flash. I can visualize the poet silently chuckling, a smirk of recognition for a man who once saw how dahlias can set fire to the sun.

Poems and photographs are buddies. They swirl around each other in mesmerizing ways, passing ideas back and forth, the limitations of their forms keeping them from touching. For a measly twenty five bucks I have plugged myself like a thumb drive into the dangling end of this particular continuum of thought. A book is a tool. Now that this one is with me, how will I use it? We’ll see. Of course, I can’t talk to Williams to find out how he actually felt. From my distance I have to do a lot of guesswork.

Bill Jenkins always liked to point out how in Incisions, Hollis Frampton suggests that photography lives between the complimentary vanishing points of memory and conjecture. Frampton says, “the confused plane of the Absolute Present, where we live, or have just seemed to live, brings to irreconcilable focus these two divergent images of our experience of time.” Yeah, there are lots of pictures; they twist in different ways in different hands. The important thing is that time persists, so it stands to reason the pictures’ll never stop twisting.