For the past 40 years, Deborah Butterfield has been creating large-scale sculptures of horses. She received her BA and MFA from UC Davis, and divides her time between her ranch in Bozeman, Montana and a studio in Hawaii. Her work is in many museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Currently her work Three Sorrows is on view at The Old Jail Art Center in Albany, Texas through January 30, 2020.

Colette Copeland: Let’s discuss the origin of the horse in your work. In a Widewalls article from 2014, writer Milja Ficpatrik stated that the horse has historically been a metaphor of male domination. I thought this was curious, since I equate the horse as an object/subject of male domination.

Deborah Butterfield: The horse was not a metaphor for male domination; it enabled male domination. It was like having a tank or a gun or a bomb. Whoever had a horse had an advantage over others who did not.

CC: When did the horse first show up in your work?

DB: From 1970-1973, I was at UC Davis for undergraduate and graduate work. It was during the Vietnam War. I felt guilty, because people I knew were getting drafted. And while I was grateful that I couldn’t be drafted, there was a lot of guilt living everyday life. I did experiment with some political art. I made porcelain ashtrays in the shape of Cambodia that said, “dump your ashes here” and sent them to Frank Church and George McGovern. I received some interesting letters in response, but ultimately, I wasn’t very successful making political work.

One of my teachers assigned the ancient Chinese text, I Ching and one of the tenets said to be like the sun at mid-day, which I interpreted as “to shine.” Since I wasn’t very good at much besides making art, I gave myself permission to accept being in the studio and made the first horses for my graduate show.

CC: When you create the horses, do you consider their gender?

DB: The first horses were self-portraits; they were mares. This countered the historic iconic statues commemorating war, featuring generals sitting atop big stallions. These statues have been the metaphor for male domination and power. Now we see them toppling down. I am a speciesist, and do not believe that man has dominion over all the earth. The horse has been just as subjugated as women. I am a serious rider; I ride dressage. I have a lot of discipline with my riding and my horses, but it is based on love and respect.

CC: After the graduate exhibition, did you continue making mares?

DB: For many years, I made mares. The next series of works were made with mud, sticks and straw on a steel armature. It looked like a flood had deposited a pile of debris on a riverbank. I had a review in Artforum and the reviewer’s first sentence said that Deborah Butterfield’s horses have no genitals. At first, I was devastated, but I also thought it was hysterical. To counter that, the next horses I made had sticks and antlers sticking out everywhere.

However, the horses were lying down. They were made of the ground and were laying on the ground. I thought of them as myself, referencing the reclining nude from art history, but also as the prey in the gallery, as the predator wolf-critics stalked outside. A horse can sleep standing up, because they are a prey animal. When a horse lies down, it is because they feel safe. For me, that was an indirect way of saying we have to make ourselves vulnerable. We can’t be shrill and defensive in a man’s world. We have to show our strength by our resiliency.

CC: How did you make the transition from sticks and mud over the steel armatures to the bronze casting?

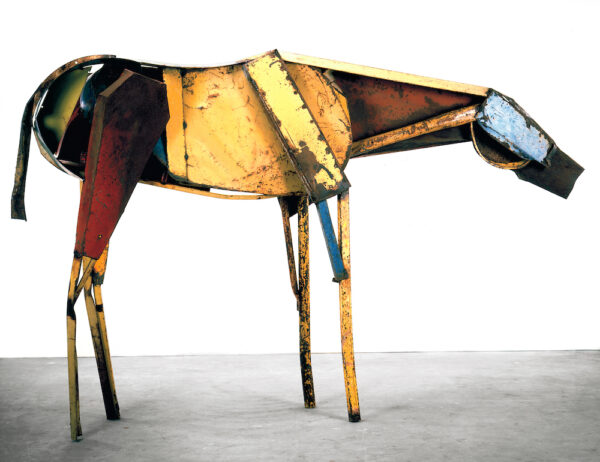

DB: In 1979, we bought a dilapidated farm in Montana and I had to remove three rows of old fencing. Rather than buying new steel, I decided to repurpose the metal fence posts. This also led me to expose the interior space of the horse, as an expression of an emotional state. Rather than a solid structure, the horses became a three-dimensional drawing.

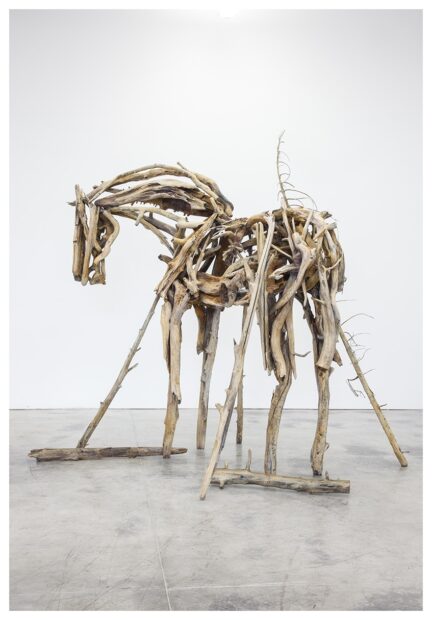

A few years later, I was invited to make a commission for the Walker Art Center’s sculpture garden in Minneapolis. They introduced me to the Walla Walla foundry in Washington, and in 1987, I made my first big bronze horse. I drove a truck to the foundry full of sticks that I thought I might use and they cast them in bronze for me and then we welded them together. It was the most fun I’ve ever had. It was uncanny how much they looked like the real wood after casting, and then we could patina them, using the torch, paints and different acids to give them a more realistic look. This process allowed the sculptures to live outside. Much of my previous work was so fragile that I spent too much time as a conservator, rather than a creator.

CC: Much has been written about your collaboration with Walla Walla and the meticulous process of collecting the twigs and branches, as well as found objects/debris, creating a model for the sculpture, documenting it extensively with photographs, then disassembling, and casting each branch, then reassembling through welding, followed by a unique patinated finish. The process is a life cycle — not only of your collaborative, creative practice, but one that gives life to the horse, rendering it immortal in bronze.

DB: I have to be very clear here that Walla Walla foundry does the photographing, deconstruction, and casting of the work, and it takes about nine months to make a work with twenty or more specialists working on the project. I keep an inventory of cast bronze “armature” sticks at the foundry and with an assistant, I weld an armature that remains at the foundry. I return after the casting and we make changes, grinding down mistakes, welding new appendages, etc. Then it is sand-blasted and I do the color/patina on it. It’s a very time-consuming and physical process. Each work is unique.

CC: One of the overall themes in your work is the connection to the earth — the place from which the horse is born. The works address the fragility of the environment and animal world.

DB: For over 35 years, I have used the horse as a metaphor for the Mother Earth. They represent what is/was wonderful about our earth — what we haven’t ruined yet. My animals keep me honest and keep me striving to be the best I can be. They are witnesses on the earth.

CC: In the 2017 Danese Corey Gallery catalog, I enjoyed seeing photographs of some of the sites where you collect the wood, such as the Millie Fire, near Bozman, Montana. How do the specific sites of collection imbue the sculpture with additional layers of context and meaning?

DB: The burned word is certainly a witness to manmade and natural destruction. I am fascinated by how matter changes. When wood has been cut or burned or flooded, the story of the experience is embedded in its molecules. That is also true of manmade materials. While I am interested in the narrative, I am also interested in keeping the work formal and abstract; having a dialogue with the materials as I create. It isn’t until the end, when I add the neck and head, that the work becomes personified and figurative.

CC: Your work Three Sorrows on exhibit at The Old Jail Art Center in Albany includes collected detritus from the 2011 earthquake in Japan. This powerful work evokes a lot of emotion for me. I think about the butterfly effect, how we collectively remain ignorant of how each person’s individual actions can cause a ripple effect across the world. Many writers have referred to your horses as ghosts or skeletons. I see this horse as the lone witness to the devastation and the long-reaching impact from the earthquake, to the tsunami, then triggering the Fukushima nuclear disaster. How did this work come about?

DB: I read an article that the Alaska Bay Keepers were bringing a boatload of debris to Seattle. The tsunami caused the debris to travel across the Pacific from Japan to the Alaskan Islands. The article stated that volunteers were going to sort through the debris and recycle it. There was a problem with permitting and the city was not going to allow sorting, so the pile was going to the dump. The Bay Keepers put me in touch with the waste management company and they agreed that it would be important for me to make work with those objects. It took several months, but I was finally able to access the materials.

I made two trips with U-Haul trucks, salvaging the material. I found a lot of things in the wreckage that were really sad, liked crushed helmets, children’s toys, toothbrushes and children’s shoes. I wanted to keep the work restrained and not play the heavy emotional card. I tried to listen to the material and let it speak to me. The large, blue plastic piece in the Three Sorrows horse represents the ocean to me. And the other pieces are like land masses.

CC: I read in Gretel Erlich’s catalog essay that you hosted some Japanese artists at your Walla Walla studio to view the work and asked the Japanese painter Keiko Hara if the two tsunami horses and scattered debris were respectful. Erlich stated that you wanted to ensure that the work was not an invasion on survivors’ privacy. When you asked if you should have an alter behind the horses, Hara replied that the horse is the alter. What a powerful testament and memorial to the horrific tragedies. Where did the title for the work come from?

DB: Are you familiar with Gretel Erlich’s book entitled The Solace of Open Spaces? She writes a lot about Greenland, the glaciers, and global warming issues. After the tsunami hit, she went to Japan, interviewed survivors and made a beautiful book called Facing the Wave—A Journey in the Wake of the Tsunami. She refers to the events as the three sorrows — earthquake, tsunami and meltdown. I asked her if I might use the title for my work and she graciously agreed.

CC: I look forward to reading it. You mentioned that you were at the Walla Walla foundry last week. What are you currently working on? What in life are you most excited about right now?

DB: I just finished work for an exhibit in Chicago for next fall, 2021. I used more of the burned wood from a different fire in the work. I also worked on two other pieces with different types of wood and am excited about the line quality in each work. I love working.

With life, I’m trying to focus on some positive aspects about the impact of the virus. My life is not a lot different whether I’m locked down or not. Having the permission to just be and be home without the pressure of having to travel all over is a great gift. I’m able to be with my horses on a more consistent basis, and garden. Hopefully there will be more equilibrium after this is over. I have to believe that something good will come out of something this terrible.

Butterfield’s work is on view at The Old Jail Art Center in Albany, TX through January 30, 2020.

14 comments

I always loved Deborah Butterfield’s work and enjoyed introducing it to my high school art students. I do wish I had had this article at the time to give more context to her work. What a wonderful story.

Thank you Dave for taking the time read and comment. It was an honor to interview Deborah.

A great artist and an old friend. Thank you for the wonderful interview!

I went to first grade with Deborah (Rolando Elementary, in San Diego, or La Mesa, more specifically, CA.) We were both horse crazy, and pretended to be wild horses running around on the playground. I just retired from 32 years of teaching art. I introduced my students to Deborah’s horse sculptures via a video I purchased of her and her work. The horse has always been a part of my own art, a great inspiration to me. My husband, an ex rodeo cowboy understood my passion and bought me my first and only horse…loved that beautiful blue roan.

Hi Kathleen,

Thank you for sharing your personal story about you and Deborah growing up. I love the vision of you both pretending to be wild horses. Congratulations on your retirement. May you continue your art and horse adventures.

Great interview! Thank you for bringing insight to her approach and practice as an artist. The Three Sorrows currently on exhibit at The Old Jail Art Center in Albany is incredible.

Thank you both very much for such a thoughtful exchange. As a staff member at the OJAC, I get to see Butterfield’s Three Sorrows every day (at least through Jan. 30) and it truly has offered inspiration and hope through these strange and difficult times. Erlich’s book shares the same. In it, she writes writes, “It’s said that if we can drop the bothersome appendages of egos and sugar lumps, we will begin to feel an immense caring for others, for otherness, for all kinds of suffering, and in doing so, we will be able to exchange ourselves for others. If we try, strange sympathies will fill us and the power of empathy will fuel us forward.”

Kodai no uma translates as ancient horses. This installation comes from the idea “Umarekawaru”, to be reborn. A buddhist philosophy related to reincarnation but also shinto and the concept of life transforming from animate to inanimate and back to animate. “Ume wa Nandomo Umarekawaru” is a popular Japanese song which translates: Dreams are reborn again and again. Thus my horses (uma) show strength (chikara) as they transform from rock to flesh, and interpreted into fired clay. These works have been seen by audiences at Mother dog Studios and also the gallery at the Silos in Houston. I hope to see Deborah Butterfield’s tribute, “Three Sorrows”.

Thanks Colette for the interview.

Thank you Amy for sharing Erlich’s quote. It is particularly salient at this moment in time.

Thank you Jo for providing the translation and cultural references for the work, allowing us deeper insight/context into the work.

So I went to Albany on Wednesday. I thought Three Sorrows was beautiful and sad and inspiring. Thank you for your insightful interview that explained so much.

Thank you fir writing this beautiful article and sharing the interview. They were both a joy to read. Happy holidays.

Thank you Penelope and Cindee for taking the time to read the article/interview and for your comments. I had the pleasure of seeing Deborah’s work outdoors at Crystal Bridges Museum last week and it was stunning. Best wishes to you all for a restful holiday.

So happy to see this article on Deborah. She is doing such powerful work. As a 64 yr old artist and a dressage rider I am also happy to read that she is still riding.

Thanks Susan for taking the time to read and comment. Glad to hear that you are still riding as well.