The title of Joe Harjo’s focused and epic solo show at Sala Diaz in San Antonio, The Only Certain Way, comes from the 16th-century Spanish conquistador Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Cabeza de Vaca was a devout Christian and eventually became a faith healer to the indigenous people he encountered/conquered in what is now the American Southwest, and wrote that the conversion of people to Christianity (and by extension a colonial subjugation) “…must be won by kindness, the only certain way.”

This quote crystallizes a particularly pernicious element of colonialism, seen far and wide from Bartolomé de las Casas to the film The Mission — the idea that if the gospel is spread truthfully and with compassion, then the rapacious conquest of lands and people is muted, and made somehow okay. But what is this way exactly? It is a destruction, a branding, a forced transfer — of a person, a culture, a place.

Harjo, who is a member of Muscogee (Creek) Nation, forms an emotional and intellectual refutation to this way through a disparate series of forms and concepts. There are four types of works in the show: performance prints, photographs, a video piece, and two large crosses made up of memorial flag boxes filled with patterned Pendleton textiles.

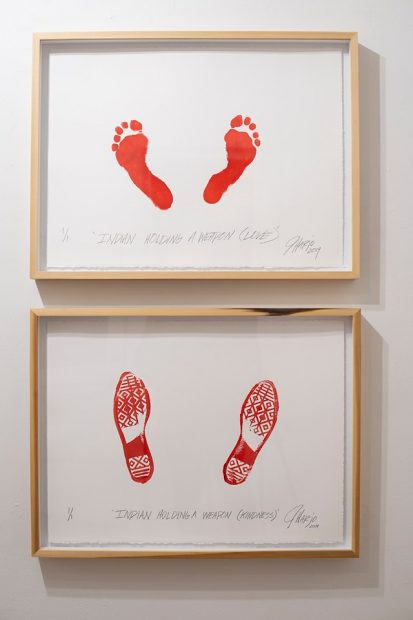

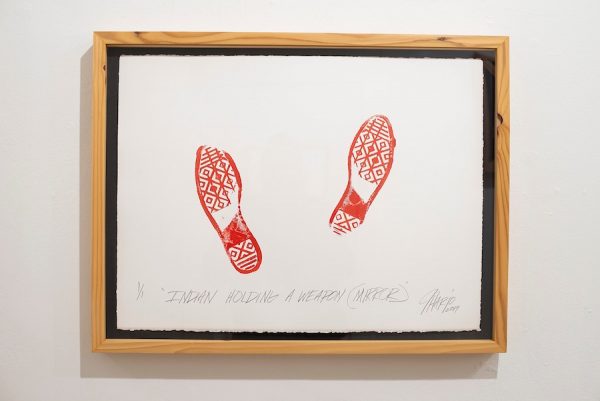

The performance prints make up the largest section of the works. They’re formally simple but conceptually dazzling. For each, Harjo dips his feet (or sometimes his Chuck Taylors) in clay-colored (red) paint and stands on paper. Each of the performance prints are titled Indian Holding a Weapon, followed by a concept or object in parentheses (e.g: Love, Kindness, Promise, Apology, Mirror, Breath, Medicine, Blood, DNA).

Harjo says of the the process:

“When I am ‘Holding’ intangible ‘Weapons’ I consider my presence, my breathing, the blood in my veins and my conscious and how that connects me to my ancestors in an immediate way. (Love, kindness, self-doubt, breath, mirror, etc…) If I am holding a tangible ‘Weapon’ then I consider my presence in relation to the object and how it is or has been used as a weapon and by whom and the lives that it has affected, both negatively and positively. (mirror, gun, drivers license, etc…)”

The performance prints are aesthetically beautiful. There is an embossed tactility to them — the loping lines of his footprints resemble the topography of the American Southwest; the pattern of the Chuck Taylors resemble the patterns in the Pendleton textiles. Harjo elegantly creates a lattice of associations and references.

The prints are in a dialogue with the cultural depictions of Native Americans. One thinks of the works of Frederic Remington: the Indian is usually alone, gazing out at the plains or the mountains, melancholically pondering the end of his way of life. This sad nobility is a perverse holograph of settler colonialism — seeking to romanticize what it destroys. These performance prints answer the illusions with the absence of form and the physical evidence of it. Those “Indians” painted by white men weren’t real. Harjo is, here is the record.

The titles of the performance prints create a complex conceptual visualization, replacing the myths of the “Noble Chief.” The titles are written in pencil by Harjo, just beneath the clay-colored footprints; the faintness of the graphite contrasts with the deep red clay tone. The structure of the titles (Indian Holding Weapon (Love)) works on multiple levels — they comment that in conquest (which Cabeza de Vaca, despite his dewy proclamations of kindness, certainly was engaged in), everything becomes a weapon, and everyone a threat. They also resist mental visualizations. What does an Indian Holding Weapon (Apology) look like? Even the ones that specify an object read almost as a riddle or a koan; what would one see in Indian Holding Weapon (Mirror)? Yourself? Throughout the show, Harjo grapples with erasure and what that means — physically, emotionally, intellectually, and historically. He uses the small space of Sala Diaz to great effect, and places the two (Mirror) pieces the greatest distance from each other, as if the imagined reflections were pushing themselves farther apart.

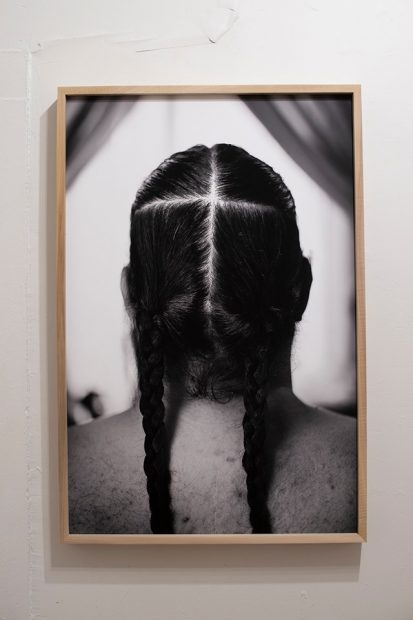

The large and exquisitely rendered and detailed photographs provide a direct emotional ballast to the performance print series. In Mark of The Beast, Harjo’s hair is tightly parted, revealing a white cross pattern on his scalp. The message is devastating: the cross of conquest and oppression to bear (the beast) may go on forever, tattooed on your skin; a hand grabbing the back of your head. In The Only Certain Way…EXIT, Harjo shoots the hallway and double doors of The Southwest School of Art in extreme contrast — the gaps between the doors and the floors create a cross, and the stark ambience of the work suggests a hospital or “the tunnel” at the end of life. Again, the message hits like a hammer. The only certain way out of this devilry is death.

The pièce de résistance of the show are the two large crosses. The Only Certain Way…FEAR is made of white patterned Pendleton towels in memorial flag pine cases assembled into a cross, while The Only Certain Way….FAITH uses vibrant, multicolored towels. Part of Harjo’s genius is his use of space and placement for highly rigorous and conceptual ends. The crosses parallel each other (like so much of this show), and uncoil multiple meanings. The white cross of fear shadows the cross of faith — stalking it, leaching it of color. The multicolored cross of faith can also be seen as the cross of fear — cloaked in the aesthetic of the natives, but underneath, the ground is the same white fear. The crosses form a reflecting whole of colonialism, and its ability to shift between supposedly friendly postures — like Cabeza de Vaca — and the apparatus of violence behind them to achieve domination.

This is an understandably sad and unsettling show. It grapples with these legacies with great sophistication, and is bracingly unsparing and unsentimental. However, Harjo “ends” the show (with its placement at the end of the Sala Diaz hallway) with an ecstatic video piece titled A Heretical Act of Resistance. In it, Harjo methodically braids his hair, and upon finishing, he stares resolutely, confidently, and openly into the camera. There is another way. His own.

At Sala Diaz, San Antonio through March 13.

1 comment

Great read on an amazing show! Harjo’s fantastic feat might be to equalize the artist & viewer in their consciousness as they gaze not only on his work, but at their own reflection in it.