Ever since the election and the weeks following President Trump’s inauguration, many artists I know (myself included) have struggled to locate the same kind of meaning within their work as they did before, to question the value of its content amidst what I think most of us in the arts view as a new dystopian political landscape. How does an artist acknowledge and participate in the post-factual world swirling around her? And what does it mean if she chooses to negate it?

I think it’s important to remember that all work is fundamentally political in nature whether or not it is consciously so. It doesn’t have to be activist or didactic, although it could be; it could be subtle, introspective, even hermetic. But I wonder if, in these increasingly urgent times, the artist’s role has changed: perhaps political potential or relevance rests not so much with what the artist makes, but rather the fact that she persists in making it. If this is true, we might ask: are artists activists anymore? If not, where does the power lie?

So I also wonder: If an artist’s political role lies less in the product and more in the act of making, perhaps the new—or more potent—political activists are curators. That may be alarming to some: the idea of relinquishing even more power to these real or perceived gatekeepers. But we have seen in the past decade a rise in the sense of social responsibility among curators, and not just the Nicolas Bourriauds of the world. More so than the rise of social practitioners and the curators who champion them, we’ve seen an increasing reconstitution of modernist history with the inclusion of other, previously obscured historical narratives that extend beyond the trope of heroic white men making large-ass paintings.

Social responsibility is a wonderful thing, but I think there’s a different opportunity now as curators exercise and disseminate critical thought, which is to constantly reassemble relationships between artworks that may question and even interrogate the very agendas curators have or the histories they’re attempting to reify. What I appreciate about Friendly Fire, up now at the Station Museum in Houston—while perhaps not groundbreaking—is that it does just this via an intergenerational cacophony.

A problem I’ve had with a few previous exhibits at the Station Museum is that while aiming to be politically provocative and socially engaging, they tended to preach to an already largely liberal choir. Shows like those even arguably cause more harm than good: after all, while we were all busy agreeing with ourselves and applauding each other on our social awareness in the comfort of our own echo chamber, Donald Trump was busy getting elected president. But even though Friendly Fire opened three days before the election, it’s as if it anticipated the outcome—and instead of telling us didactically what went wrong or how to fix it, it groups different works together that instead quietly pose questions about how to exist or even how to be resourceful in this new paradigm.

Friendly Fire didn’t get it all right. The Station Museum played it too safe by organizing the show in a kind of curatorial sandwich: the folksy elders Forrest Prince, Jesse Lott, and Noah Edmundson parenthetically flanking their younger, more contemporary counterparts, when everyone could have benefitted from more commingling. The generational separation may not deliver full justice to the contemporary relevance of Prince’s, Lott’s, and Edmundson’s work, but the inclusion of their work alongside Alabama Song or Kaneem Smith (to name a couple) nevertheless injects a renewed social relevance beyond the verging-on-tired notion of the “folksy visionary” label these veterans keep getting tagged with as their legacies solidify in Houston’s art-historical canon.

In this context, Forrest Prince’s work feels especially introspective, strange, and plausible. In a dizzying world where facts no longer seem to matter, should we turn our backs on one institution (government) in favor of another (religion)? Walking through his work, we can almost feel him whispering to our world, divisive and unmoored: “Y’all need Jesus.”

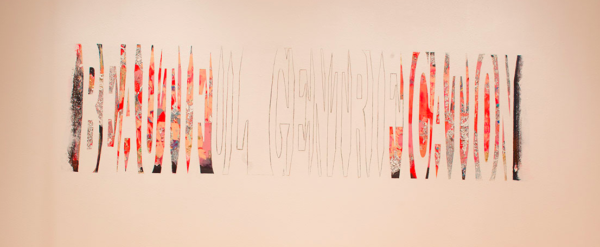

Jesse Lott’s figures feel mournful here; regardless of media or scale, their open arms feel scared, hopeful, and desperate. They read as subtle memorials of people choosing to carry on, made up of all and any materials available to Lott at the time. His figurines pair nicely with Lovie Olivia’s excavation of the gallery wall. Carving out the words “BEAUTIFUL GENTRIFICATION,” Olivia isn’t necessarily providing an indictment, nor support of, gentrification. Rather, she peels back the layers, the material history of a building to ask questions about what happens to the history of a culture or even to the texture of a place when it fundamentally changes over time. The layers she carves out and splay along the wall feel fungal and viral—simultaneously organic and obliterative. And this is why the pairing of her work with the multi-media work of Lott, Prince, and Edmundson is so important: Beautification (2016) doesn’t simply read as a statement on gentrification here, but rather as the first question toward thinking about how it can be dealt with with the resources at hand.

Robert Hodge’s installation Few of My Favorite Things (2016) similarly benefits from the ethos of resourcefulness at play in Friendly Fire. While he describes in the wall text this work as “a multi-sensory immersion in the aesthetics of black angst and rage,” it strangely feels weathered and loving, and—a little like Lott’s work—memorializing. And that kind of infusion of love here makes Few of My Favorite Things all the more complicated and interesting: as painful examples of exploitation and racism abound in this work, they also read as some of the building blocks that made Hodge who he is. The homey living-room atmosphere reads simultaneously as an open wound and a badge of honor.

To privilege curating over the potency of an individual artwork isn’t to say that works can’t stand on their own, and that certainly isn’t the case with the works in this show. But it’s important to remember how the content of a work can change—or previously unnoticed content within a work can emerge—simply by conversing with the other work (and even quite different work) it hangs beside. Asking each other to continuously rethink what we assume about an artwork feels perhaps more pertinent than ever.

‘Friendly Fire’ runs through March 5, 2017 at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston.