We need to get a few things straight about Afro-Futurism.

Afro-Futurism is an attempt to link the future to the past/present. It considers what “blackness” and “liberation” might look like in the future, real or imagined. Deeply rooted in history and African cosmologies, its culls pieces of the past/present, technological or analog, to build on the future. Not thwarted by historical limitations, the Afro-Futurists are deeply invested in the power of a positive future for blackness.

The seminal figure, the alter destiny, the presence of the living myth was, of course, Sun Ra—musician, composer, pianist, philosopher and teacher—whose interest in science fiction was rooted in the notion that African-Americans, since they had been written out of history, should be prepared to write themselves into the future.

It’s after the end of the world, don’t you know that yet?

Stressing the importance of becoming proficient in a range of new technologies, he wanted Africans everywhere to play a part in engineering their own futures rather than letting “others” construct them. He saw a people living on the edge of a dime, in the confines of a segregated cultural mythology adjacent to the modern world. Not sure if he read Joseph Campbell or Sir James Frazer but he definitely understood the need for cultural myth. He was trying to engage a people in recognizing their power in shaping what “the future” meant.

“Myth speaks of the impossible, of immortality. [Black people] need to try the impossible.”

Everybody straight on that?

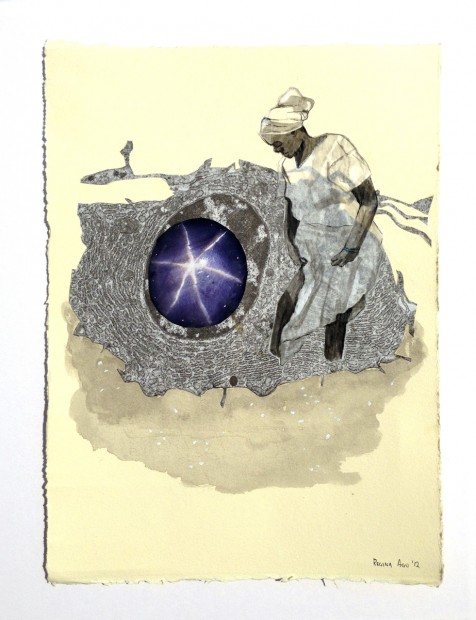

Regina Agu, “A Rare Specimen (Mami Wata Suite No. 3)” (2012) Collage, gouache, parchment on paper 10 x 13 inches framed

Regina Agu’s exhibition at Fresh Arts Gallery, Visible Unseen, is really about time and the future. Using the late Akilah Oliver’s essay of the same name as her point of entry, Agu aims new drawings and collages in the direction of underserved mythologies, ignored collective memories and moribund histories. The Virgil she employs is none other than Black Beauty herself, the black female body, as it tours her toward issues of multiple identities, a shifting sense of home and ignored scientific accountability.

With roots in Nigeria and Louisiana and having lived on several continents, negotiations have been a part of Agu’s being for quite some time. Home and identity have been brokered exercises since she was 11, leaving Houston to live in Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo and South Africa. Displacement calls into question notions of authenticity and hybridization of the familiar.

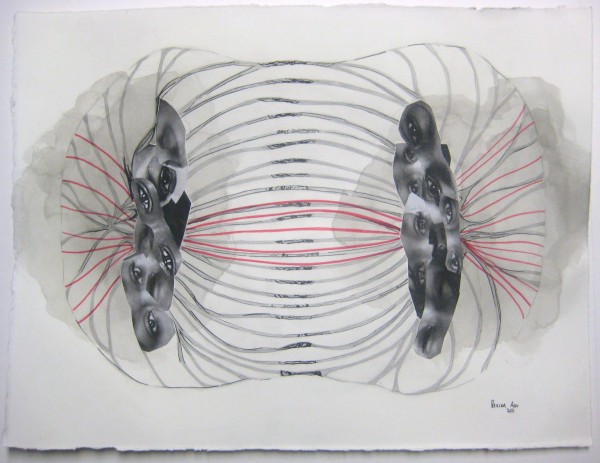

In Shrine, Agu homages an oft overlooked part of her being, the first American component that is usually muted by her visible African beauty, calling into question myopic and outdated boxes of identity. Utilizing the African mythos concerning twins, Changeling speaks of the necessity to morph and transform, many times forced, hardly ever comfortable and usually at a great price. For her, this in turn circumvents the whole notion of authenticity. Her tongue-in-cheek response in Guaranteed Wax Block Prints brings to light the history of imitation and mimicry that follows an original. The history of African wax print fabrics began with the Dutch in of all places, Java.

Looking to expand their foreign markets, they began flooding West Africa around the end of the 19th century with mass-produced batik imitations. “Authentic African fabric” is turned on its head, for the production and design are by Europeans, with little or no African input of design or motifs. Pipes or rolls of fabric, somewhere Magritte is laughing his ass off.

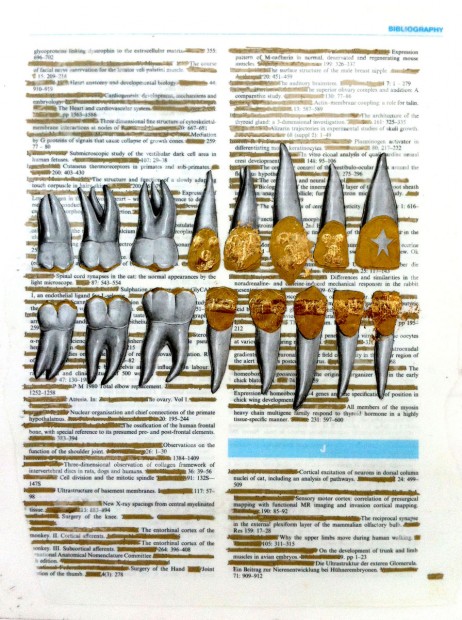

“Dental Records (Heirlooms)” (2012) Gold leaf, gold paint, collage on vinyl film, gold paint on vintage textbook paper 11 x 14 inches framed

Beauty and the binary system of value placed on the black female body are of course hot button items. Agu subverts this discussion concerning worth by employing an ally historically linked to Africa—gold. In Dental Records (Heirlooms) Black beauty’s adornment and the conflicts that ensue regarding her “ladylike” or “hootch” perceptions are played out against gold’s dazzling yet exploitive past. The toll inflicted by this constant barrage of negative perceptions are not so readily absorbed by ventricles taxed over time, leaving self worth and value in traumatic states as witnessed in Adorned.

Agu’s most ambitious discussion points its finger at scientific accountability. There is a longstanding distrust and aversion to medical care within the African-American community. The primary source of cadavers for medical schools from the late 18th century through the end of the Civil War came from slave and free black cemeteries. Many of the Southern teaching hospitals performed new surgical techniques and demonstrations on African-Americans exclusively. During the Great Migration, one of the rumors used by Southern employers to intimidate their workforce into staying in the South concerned the feared Night Doctors. These ectoplasmic practitioners roamed the streets of the North at night, hunting down and killing African-Americans for dissections. And of course, the Tuskegee Experiment still festers.

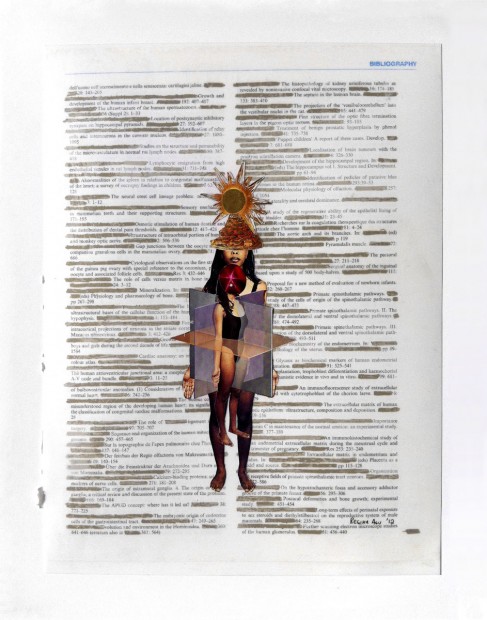

Regina Agu, “Oracle” (2012) Collage and gold paint on vinyl film, gold paint on vintage textbook paper 11 x 14 inches framed

Introduction to… brings into question those tally sheets reticent of the erasure of individual histories, albeit in the quest for knowledge. She presents a celebrated who’s who list of of scientific research, including Dr. Gray in his anatomy class, those noble, dedicated pioneers of science who day-in and day-out turned down the volume on their humanity meters to advance science. Eyes saturated on the rarified air of scientific privilege develop nearsightedness (myopia) and cross eyes (strabismus) to the common humanity of their test subjects.

Cooking the books withstanding, the real issue deals with the discounted value long attributed to the black body. Enter Night Doctor.

Employing the backdrop of a cell in mitosis, Agu revisits the story of Henrietta Lacks. She is, if you remember, the African-American woman whose treatment for cervical cancer at John Hopkins unwittingly became the source of an immortal cell line for medical research. Her cells were the first human cells grown in a laboratory that did not die after a few cell divisions. Since their discovery, the famed HeLa cells (named after the initial letters of her name) have been cultured into over 20 tons, shipped worldwide and involved directly in over 11,000 patents. By now, the more erudite of you have probably guessed where this is going. Her family was never formally contacted by John Hopkins of their findings (they learned about them in a Rolling Stone article some 25 years after the fact) and have received nary a dime in compensation.

For Agu, the promise of the future deals with unflinching embrace of the past/present. It is a gathering of the tribes (don’t get this twisted now) of the “Black Atlantic” in particular, in loud celebration of our ethnicities, voices and histories. It is about revisiting how kinfolk view kinfolk. It is about the empowerment housed in the black body. It involves the broadcasting and coding of a new system. It is the candid acknowledgement that envisioning the future in such terms is an act of artistic revolution. She seems to be in pursuit of a transformation that redefines blackness, particularly feminine blackness, on a futuristic trajectory.

Maybe the future will hold more exposure for black female artists in this city. One thing is for sure, no two moments are identical. One is certain to contain the memory left by the other. The future, we hope, is about healing.

Him: “It’s time to go…”

Her: “Where we going?”

Him: “Wherever we want…”

From Shabazz Palaces’ “Belhaven Meridian”

Is everyone cool with that?

Regina Agu: Visible Unseen

Fresh Arts Gallery

September 22 – October 26, 2012

Coverage of Houston artists has been made possible in part by the William A. Graham Fund.

________

Garry Reece is a fiction writer who lives in Houston. His work has appeared over the years in Muleteeth, ArtLies, The Texas Observer, Arts Houston, Extensions and American Short Fiction.

3 comments

“Visible Unseen” is on view through October 26th at Fresh Arts (in Winter Street Studios building) – 2101 Winter Street, Suite B11, Houston, Texas, 77007.

Great article. I agree, there is a lack of exposure for Black and Latino female artists in Houston.

However, I can’t see why this article warrants a hip-hop video at the end and other reviews do not. Just because Shabazz Palaces is a “indie” hip hop artist it does not mean he provides any insight into anything you touched on in your article.

He’s talented, yes, relevant, no.

i love the review by mr. reese

can you provide me with an email contact or pass my on

thank you

e.l.foney