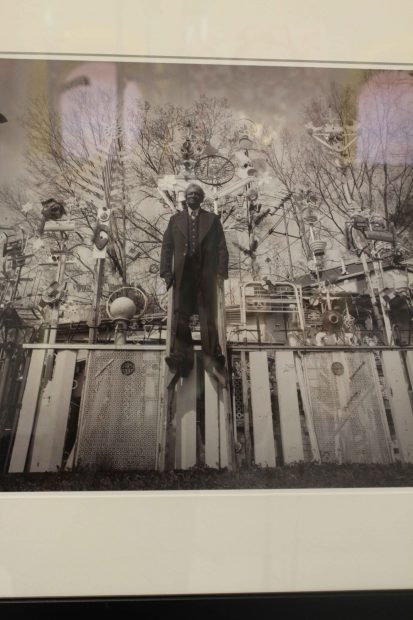

A photo of Keith Carter’s portrait of Felix “Fox” Harris installed at the Webb Gallery (with apologies to Keith Carter)

“What is art?” asked Felix “Fox” Harris (1905-1985) when a woman told him that the towering assemblage of mystery totems and strange antennae he’d erected in front of his hand-built Beaumont home was, in fact, art. The Fox wasn’t playing coy. Creating the overgrown sculpture garden that graced or obscured his domain was, for Harris, an act as organic as drawing a breath.

If you’re anywhere near Waxahachie this weekend, you can see some of Harris’ art in the Webb Gallery exhibition Lone Stars – A Celebration of Texas Culture in Art, along with work by 17 other variably obsessive-compulsive outsiders. Mounted in tandem with guest curator Jay Wehnert, the exhibition also serves as an off-the-page introduction to Wehnert’s excellent new book, Outsider Art in Texas.

Felix “Fox” Harris’ work in foreground

If we agree that artistic inspiration, in the formal art world context, springs from mysterious sources in the mind, emotions, and senses, then creative impulses that find an outlet outside that context are mystery ad infinitum. In the book’s introduction Wehnert tracks the origins of outsiderism as a discrete category of art making back to Jean Dubuffet’s pre-1950 theories of art brut, or raw art: uncooked expression that had no “need to acknowledge and respond to art history.” A most singular example whom Wehnert believes Dubuffet would have beheld is the visionary Swiss artist and mental patient Adolf Wölfli. Wölfli experienced “personal and magical transformation” through an art practice his psychiatrist described as obeying “the ineluctable.”

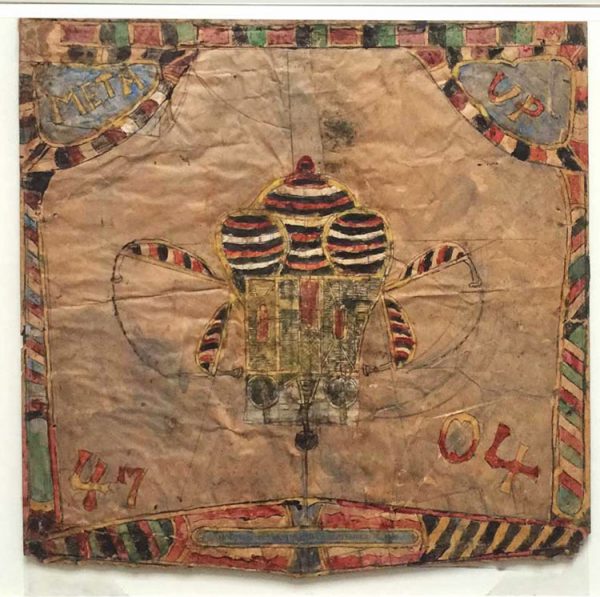

Charles A. A. Dellschau

Roger Cardinal’s 1972 book Outsider Art established the term in the larger art world, as Cardinal stated a “paramount factor” of this wild beast of cultural expression is that said beast indulges its impulses in an “unmonitored” manner that’s in defiance of “conventional art historical contextualization.” Wehnert stresses isolation as the characteristic perhaps most widely shared by the outsider. And many of the artists in the book and exhibition have indeed lived lives of relative solitude and aloneness, isolation both real and imagined that allowed for an intense focus on their art practice. Prussian native Charles A.A. Dellschau (1830-1923) spent his sunset years in Houston secretly producing twelve large handbound books of mixed media collages (watercolor, ink drawing, newsprint clips he called “press blooms,” and handwriting in English and Prussian) depicting fantastic “aeros” in which humans sailed aloft. Dellschau created his images about purported “aero” flight activity that took place years — perhaps decades — before a Baptist minister’s Ezekiel Airship briefly pierced the near heavens in Pittsburg, Texas circa 1902.

Some forty-odd years after Dellschau’s death, and after a fire in the home, the books were put out on the sidewalk as junk. Wehnert provides a succinct and peppy account of their journey to Fred Washington’s OK Trading Post and then to Dominique de Menil, who was “attracted by their eccentricity and obsessive nature.”

Richard Gordon Kendall

An obsessive drive and a “discovery” story like Dellschau’s are also common outsider attributes. One of Wehnert’s own discoveries, Richard Gordon Kendall (b. 1930) was homeless in Houston when the curator knew him from 1995 to 1998. He told Wehnert that he made drawings of the city’s architecture to keep himself “sharp.” Kendall’s repetition of content, creative use of found materials, and distinctive style, Wehnert found, “had all of the hallmarks of self-taught genius.”

Ike Morgan

Like Kendall, many outsiders found therapeutic benefits in art making. Felix Fox Harris said the practice kept “[his] mind off [his] troubles.” Former Austin State Hospital resident Ike Morgan (b. 1958) has transcended the terrors of schizophrenia with treatment, time, and a powerful, intense preoccupation with his art, which often includes Morgan repetitively painting America’s past presidents. “Part of the phenomenon of schizophrenia is the artist that is making the thing,” said the late art dealer Phyllis Kind, “doesn’t care about anything else and has a kind of primary obsession which means that he and the work are absolutely one.”

Henry Ray Clark

Incarceration, of course, is another life condition that imposes isolation on an outsider. After a walk on the wild side of gambling, drug dealing, and hustling — during which he became known as The Magnificient Pretty Boy — Henry Ray Clark (1936-2006) discovered the power of art in navigating the terrain between reality and fantasy through a prison workshop. Art allowed Clark to “travel in [his] spaceship.” The elaborate, asymmetrical patterns in his drawings generally framed a superhero-like figure in a kind of space court, beneath a glorious boast. “MY NAME IS THE RAINBOW MAN,” announced one work at Webb. “WE ARE FROM THE PLANET CALLED POT OF GOLD.” Another: “I AM THE MAGNIFICENT DIAMOND STAR FROM THE PLANET HART ROCK.” For a time after his release from prison, Clark operated a restaurant called Magnificent Burger that he decorated with his murals.

Felix “Fox” Harris

Spirits, visions, and supernatural phenomena inform many outsiders. Felix Fox Harris was born with a sixth finger on one hand; though the tiny digit withered away, African-American folk tradition credited such a child with heightened spirituality. The “cosmograms,” dolls, root sculptures, and dozens of other potent objects placed in his yard show, as Wehnert interpreted it, citing the work of historian Robert Farris Thompson, carried on “the African nkisi or protective charm tradition for the denial of hurt, for the redirecting of the spirit, and to greet provocateurs with laughter and generosity.”

Frank Jones

In the Red River County county seat of Clarksville, Frank Jones (1900-1969) was reportedly born with a veil or caul over his left eye, a condition that meant he would be blessed or plagued with “second sight.” Jones began seeing what he called “haints,” or devils, at about the age of nine. Troubled by these ominous apparitions, Jones was in and out of jail and prison, eventually receiving a life sentence. In his last decade of life, he began to draw haints and devil houses. The structures were laid out in grids in red and blue with pointed borders he said were devil horns, and they were populated with smiling haints. The devils “smile because they’re happy waiting for your soul,” Jones explained. Prison guards, who often threw the drawings away, entered one as a joke in a competition held during the first TDC art show in 1964. The work received first prize. Murray Smither then arranged an exhibition of Jones’ works at Atelier Chapman Kelley Gallery in Dallas, and Jones’ art won another prize at the University of North Carolina. Capturing his demons on paper — and the positive response of discerning aficionados — seems to perhaps have provided the tormented prisoner some peace in his final years.

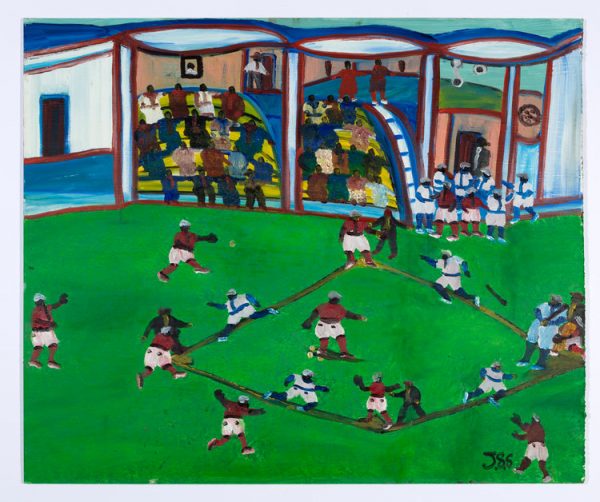

Johnnie Swearingen

“Dirt Dirt Dirt,” was the text of Johnnie Swearingen’s (1908-1993) first sermon as a boy. Leaving his Chappell Hill school after the eighth grade to work in the fields with his family, Swearingen later spent an extended hoorah out in California before returning to Brenham. Ordained a minister in 1965 through a correspondence course from Lone Star Bible School, Swearingen often set up a pop-up gallery on roadsides or on the Washington County Courthouse lawn to sell his memory paintings of the rural African-American experience. “You all talk and talk about what your art is and isn’t,” he once said to artist friends Andy Don Emmons and Bill Haveron. “I just want to paint pretty pictures.”

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua created this drawing for her McNay exhibition in 1968

Jay Wehnert’s chapter on one of my favorite outsiders, Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua (1903-1975), appeared here when the Webb Gallery exhibition opened. Chelo worked in the Kress store in downtown Del Rio, and I have often wandered down that border town’s streets and imagined its colorful past. Because of her warm family life, filled with music, poetry, performance, and her fine pen and ink work that she called “Texas Filigree Art,” one might conclude that González Amézcua’s cultural experience was broader. Yet when Jacinto Quirarte asked her, in an interview for his book Mexican American Artists, if she knew the work of a certain artist whose work he felt resembled hers, she replied, “No, I am not familiar with anything. I am not familiar with cultural things.”

Lone Stars – A Celebration of Texas Culture in Art continues at Webb Gallery through August 26. Felix Fox Harris’ work is on semi-permanent view at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas in Beaumont.

2 comments

Thanks for your thoughtful review of this exhibition and your kind words about my book. I appreciate it very much.

Let me say a few words about Gene Fowler. He’s my cousin. We share the same grand parents. Early on Gene was able to process things on a different level compared to the rest of us kids. While we were still pushing around dirt with a stick Gene was writing poetry and indulging in more cerebral activities. As we made the transition into young adults there was a realization that his talent was quite special. Not sure we ever told him, but he became our Walt Whitman.