The White Shaman mural is on the east wall of the southwest-facing shelter, so the paintings face due west.

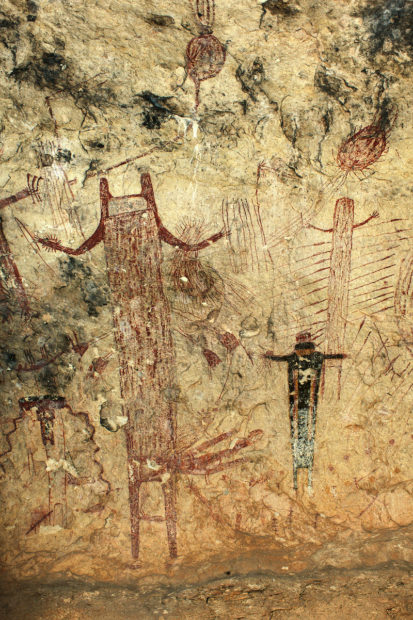

“I was overwhelmed by wonder,” recalls Carolyn E. Boyd of the first time she beheld the ancient pictographs on limestone walls in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands west of Del Rio. It was 1989, and Boyd was winning her daily bread at the time as a working muralist. Encountering the prehistoric open-air galleries with their stone canvases filled with mysterious anthropomorphs, animals, and other figures was an experience that changed her life. She wanted to know more about the seemingly abstract expressions rendered in earthen tones of red, brown, black, yellow, orange, and white.

Knowing that a serious attempt to enter the world of the artists who created these images would require a solid foundation, she acquired a PhD in anthropology. Then in 1998 she founded the Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center in Comstock, between the Devils River and the Pecos, a nonprofit devoted to “studying the human use of materials, land, and art.”

The polychromatic Pecos River style mural at the White Shaman site is approximately 26 feet long and 13 feet high.

Today, even though she has answered many of the questions that swirled in her mind that day, her sense of wonder has only deepened. Boyd shares much of her quarter-century of research in a new book, The White Shaman Mural, published by the University of Texas Press. One of hundreds of rock art sites in the region, the 26-foot-long, 13-foot-high mural is in a rockshelter on a bluff high above the Pecos River near its confluence with the Rio Grande.

As the name indicates, at least one of the anthropomorphic figures in the mural is believed to represent a shaman. In her effort to understand the narratives of the White Shaman and other Lower Pecos art, Boyd documented patterns in the artworks and drilled down into the mythologies and artistic production of Mesoamerican and Southwestern Native American cultures. She especially perceived a kinship between the ancient Texans and the Huichol Indian culture of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental range.

The White Shaman site was named in the 1980s for this striking 3-foot-tall, white anthropomorphic figure.

The White Shaman Mural, she writes, “functioned as a prescription for ritual,” sometimes involving the ceremonial use of peyote, the psychoactive cactus that grows along parts of the border in Texas and Mexico. As she argues in the new book, the artwork is also a compelling creation story:

“It shows the process of a peyote ceremony, including the transformation of the mortal to the immortal, the cleansing and binding together (the uniting) of the pilgrims, the slaying of the peyote/deer, and the offering of fire to the ascending sun. This analysis introduced other possible functions for Pecos River style anthropomorphs beyond the stereotype of their being merely representations of shamans. Shamanism was certainly an integral component of hunter-gatherer religion; however, it was expressed in the rock art alongside and interwoven with a constellation of myths, histories, and ritual practices involving a myriad of spirit beings and mythological characters.”

Some Lower Pecos artwork was created as long as 4,200 years ago, and other work is believed to be only 1,500 years old. Archaeologists and artists began studying the art in the late 1920s. Boyd notes that, for decades, three main assumptions about the art were generally agreed upon: “The rock art represents hunting and medicine cults… anthropomorphs and accompanying imagery represent shamanistic documentation of visions and glimpses of the supernatural otherworld… and attempts to decipher the art are nothing more than exercises in speculation.”

Boyd, however, sees the paintings as “perhaps the oldest known texts in the New World. Incredibly complex and compositionally intricate, these ancient murals, like codices, are pictographic writing. Far from being the idle doodling of ancient peoples, the rock art of the Lower Pecos was part of a living landscape that provided food, shelter, and a connection with the spirit world.”

Curiously, Boyd indicates that there appears to exist a fair amount of uncertainty in both archaeology and art circles about whether or not rock art can genuinely be regarded as “Art.” Though she declines to enter the debate in the new book, in an earlier volume, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos (Texas A&M University Press, 2003), she stated that imagery such as that created by the ancient artists of the Lower Pecos is not “Art” according to “the modern Western definition.”

But she also argues that the real problem is in “Western insecurities about what art does,” suggesting that we need to “broaden our understanding and appreciation” for art as “utilitarian, a part of a system of tools and techniques by means of which people relate to their physical and social environment.”

This 1933 newspaper report on an archaeological expedition to the Lower Pecos was “excavated” by Gene Fowler from a Depression-era scrapbook.

Fortunate as we are that these artworks still exist in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, it’s unknown how much longer they will survive. Many were submerged beneath the waters of Lake Amistad, created in the 1960s for flood control by the damming of the Rio Grande. Boyd and other archaeologists say that we are basically in a race against time to document the works before most if not all of them disappear.

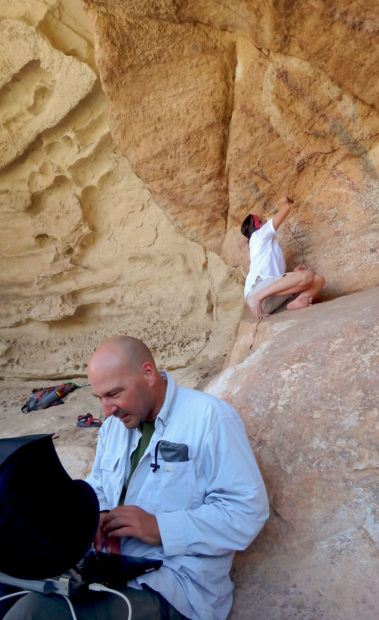

To that end, her examinations of the art include the use of such state-of-the-art tools as “3D laser mapping, drone mapping, structure from motion (SfM) photogrammetry, portable X-ray fluorescence, handheld digital microscopes, total data stations, and Wacom Cintiq Interactive Pen Displays.”

Archaeologists working with a digital field microscope. With the microscope placed at the analysis location, the microscope is connected via USB to a laptop where the microscopic imagery is viewed and photographs are captured.

Texas A&M professor emeritus Harry J. Shafer explains how the art and associated material culture have managed to survive this long in a volume he edited, Painters in Prehistory (Trinity University Press, 2013). He writes that humans first arrived in present Texas over 11,000 years ago. In the Lower Pecos region, they sought protection from the elements under the “protected canopies of the many rockshelters and caves,” where the usually dry atmosphere provided an “extraordinarily good state of preservation of normally perishable materials.”

Thus, the Witte Museum in San Antonio, which first sent artists and archaeologists to document Lower Pecos prehistoric culture in the 1920s and ’30s, today preserves a rich collection of artifacts, including such things as remnants of baskets woven from plant materials, sandals, mats, nets, projectile points, and tools of stone, wood, and bone. The museum also holds 5,200 year-old peyote effigy specimens believed to represent the earliest extant evidence of peyote usage. The museum’s permanent exhibit about ancient Texas lifeways, People of the Pecos, has been closed for refurbishing and is expected to reopen in 2017. The Witte has also taken possession of the White Shaman site through an agreement with its previous owner, the Rock Art Foundation, and the two institutions will work together to continue providing access through public tours.

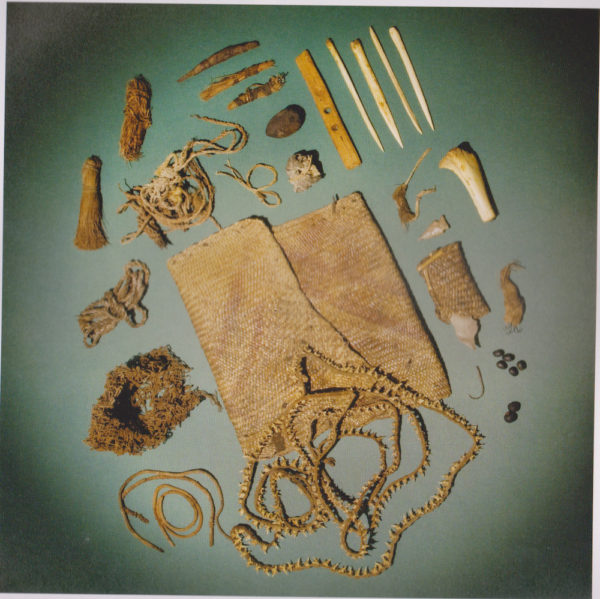

Archaeologists believe this to have been a shaman’s bag with ceremonial items, excavated in the Lower Pecos in 1933. Collection of the Witte Museum. From the book Painters in Prehistory.

An especially intriguing artifact in the Witte collection, believed by archaeologists to have been a shaman’s bag, was excavated from a burial site, likely that of a shaman, in 1933. As Roberta McGregor, former anthropology curator for the Witte Museum, writes in Painters in Prehistory, the twill-plaited bag “held 29 items that relate to ceremonial activities, including fiber bundles containing cactus thorns (possibly for tattooing); a manganese crayon inserted into the end of a deer bone (again, perhaps for tattooing); a sharp stone flake encased in its own twill plaited pouch (most certainly used for bloodletting); two woven strings of rattlesnake vertebrae; four sharply pointed bone awls; a small rawhide bag; buckeye seeds; and mountain laurel seeds. These are the belongings of an important man—a shaman—one who was highly valued in this society for his healing abilities, his relationship with the supernatural, and his leadership.”

A 10-foot-tall anthropomorph in Panther Cave with upraised arms, U-shaped head, and a feather hip-cluster-like adornment on its left side. An atlatl loaded with a dart is portrayed in the figure’s right hand, and in its left hand are additional darts as well as other paraphernalia.

In a prehistoric-art-supplies contribution to Painters in Prehistory, Boyd and J. Phil Dering report on an experimental attempt to replicate paint used by the Lower Pecos artists. It’s believed that the pigments (which in some Native languages means “power” or “supernatural spirit”) were drawn from minerals such as hematite, limonite, and manganese oxide. The experiment used deer bone marrow as a binder and yucca root as an emulsifier, ingredients that Boyd writes would have been “imbued with supernatural potency” in the eyes of Lower Pecos artists.

Over the last quarter-century, as Boyd has introduced her research to the archaeology and rock art communities, some have been reluctant to accept her findings. In a recent interview with David Martin Davies on Texas Public Radio’s “Texas Matters,” she relates an experience that would surely sway at least some hardened skeptics. “I took a Huichol shaman to see the White Shaman Mural,” she told Davies. “And he immediately began sobbing, pointing at the figures and saying, ‘They’re all here, all of my grandfathers, my grandfathers, my grandfathers… .’”

Additional resources: For information on tours of the Fate Bell Shelter and other rock art at Seminole Canyon State Park & Historical Site, go here. Listen to Carolyn Boyd talk with David Martin Davies about astronomical and other aspects of Lower Pecos rock art here. Learn more about the rock art of the Lower Pecos here. For information on the Rock Art Foundation, tours of the White Shaman Mural, other Lower Pecos sites, and Witte Museum programming, go here and here. For information on the Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center, go here, where you can also check out a very recent five-minute video. Go see some rock art.

2 comments

Awesome write-up! I think most contemporary artists are moving towards an understanding of art as “utilitarian, a part of a system of tools and techniques by means of which people relate to their physical and social environment.”

Another really fine work by Gene Fowler.