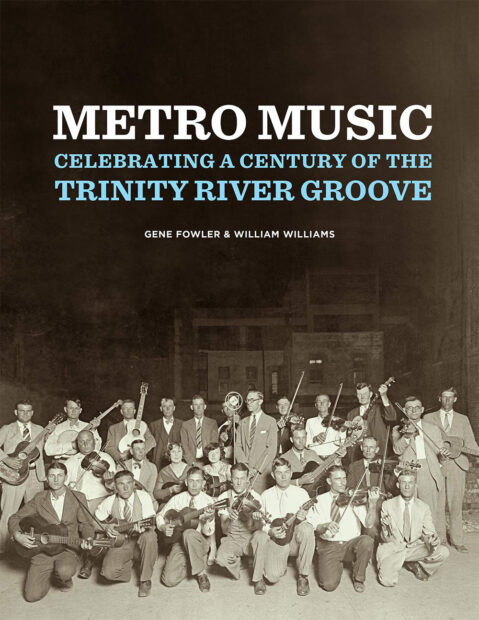

A new book published earlier this year, Metro Music – Celebrating a Century of the Trinity River Groove by Gene Fowler and William Williams, explores the visual record of the musical history of Dallas, Fort Worth, and the surrounding area from the nineteenth century to the 1960s, and also chronicles the continuing echoes of that transformative decade. With nearly five hundred images, many previously unpublished, the book moves through genres and eras that include old-time fiddlers and string bands, singing cowboys, the blues, western swing, gospel, country-western, jazz, ragtime, big bands, Tejano and Tex-Mex, rhythm and blues, rockabilly, and rock ’n’ roll.

The authors will sign copies of the book at the Barry Whistler Gallery (315 Cole Street #120) in Dallas on December 4th from 11 AM to 2 PM. The signing event will take place in conjunction with the opening of a group show, Seriality, from 12 to 3 PM.

The authors will sign copies of the book at Record Town (120 St. Louis Avenue #105) in Fort Worth on December 5th from 2 to 4 PM.

The following is a semi-random selection representing the nearly five hundred images in the book.

Fiddler W. B. Chenoweth and Joe Chenoweth, “world champion boy banjoist,” were two members of the Dallas string band, the Chenoweth Cornfield Symphony Orchestra. They were some of the first artists to record commercially in Texas when OKeh Records set up a temporary studio in Dallas in the fall of 1924. W. B. Chenoweth was also an inventor, claiming credit for the “invention of the first six-cylinder automobile in 1899, a flying machine in 1908, a farm tractor controlled from the plow like a mule, and a machine for extracting electricity from the air.” When he tried to sell his automobile idea in 1899, a Philadelphia engineering firm wrote back, “You must have been kicked in the head by a mule when a small boy which left you laboring under the delusion that a self-propelled vehicle could be driven over a public road at 25 miles per hour.” Image courtesy of Joseph Thomas Chenoweth.

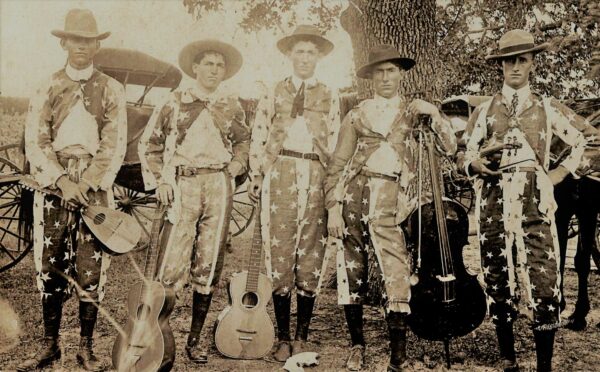

The student musicians in the Johnson School Fiddle Band, photographed in Stephenville in 1904, may not look terribly enthusiastic, but their outfits make up for it. Image courtesy of the Stephenville Historic House Museum.

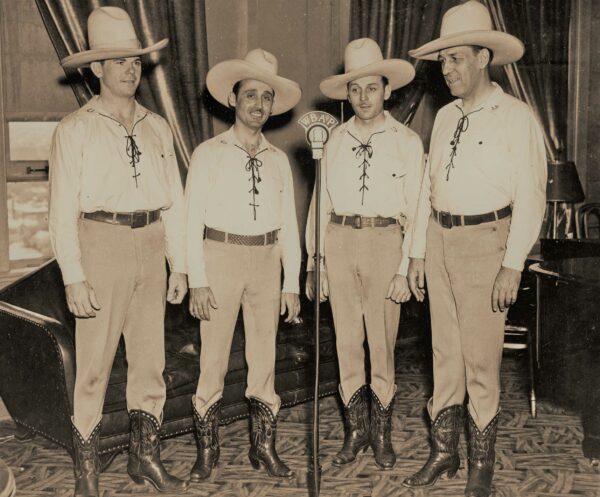

Above is the first iteration of the Chuck Wagon Gang on Fort Worth’s WBAP. “Big Joe” (at far right) was said to be “the only cowboy in captivity who wears his spats in wintertime and has never been astraddle a horse,” while “Little Joe” (second from left) was reputed to be “the meanest and toughest man for his size in the whole gang.” “Flapjack Jude” (second from right) lived in fear of “singing a high C and not being able to get down off it.” Image courtesy of the University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections.

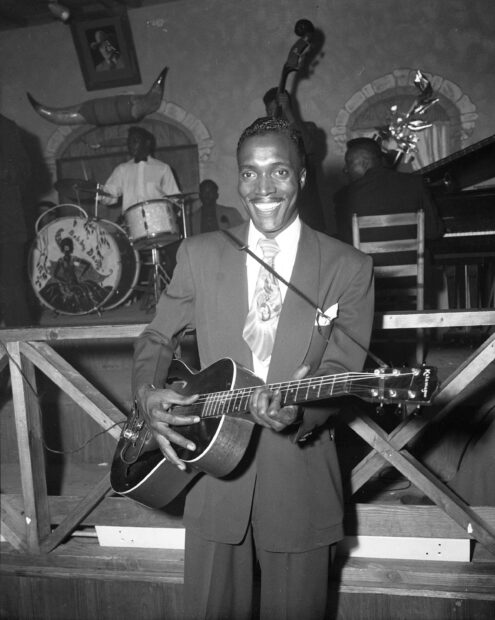

Dallas bluesman A. D. “Zuzu” Bollin, whose name references a popular ginger snap cookie, released his first recording, “Why Don’t You Eat Where You Slept Last Night?,” on Big D’s Torch label in 1951. Bollin maintained that Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby (yes, that guy) waged a campaign to keep it off local radio and jukeboxes when the artist raised his booking fees after the record’s initial splash.

Before it became the seminal blues mecca, Fort Worth’s Bluebird nightclub building served as a taxi stand. T-Bone Walker’s final public performance may have taken place at the Bluebird in 1974, when he sat in with Robert Ealey and his Five Careless Lovers. Image courtesy of Record Town, Fort Worth.

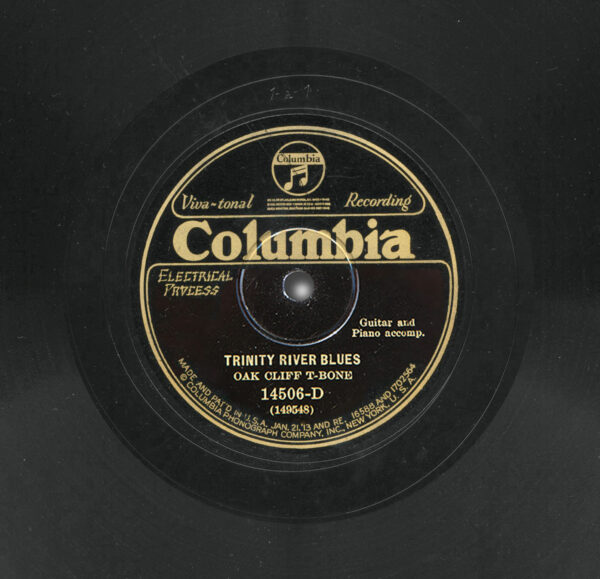

Above is T-Bone Walker’s first record, 1929. “That dirty Trinity River sure have done me wrong….” Image courtesy of George Gimarc.

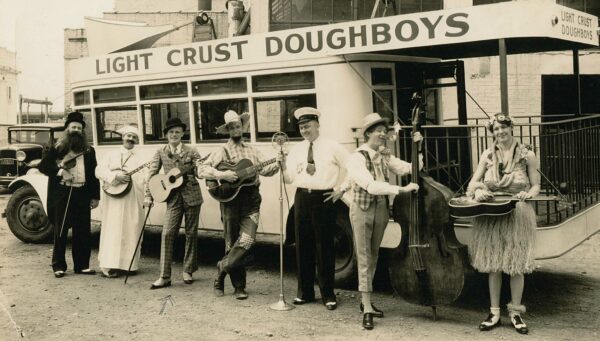

A 1933 image of the first western swing supergroup, the Light Crust Doughboys. We don’t know the occasion for the costuming, but they look pretty cool. The group’s announcer, W. Lee “Please Pass the Biscuits, Pappy” O’Daniel, at the microphone, used his radio-star-flour-power later in the decade to become governor of Texas and then a United States senator. Image courtesy of Kevin Coffey.

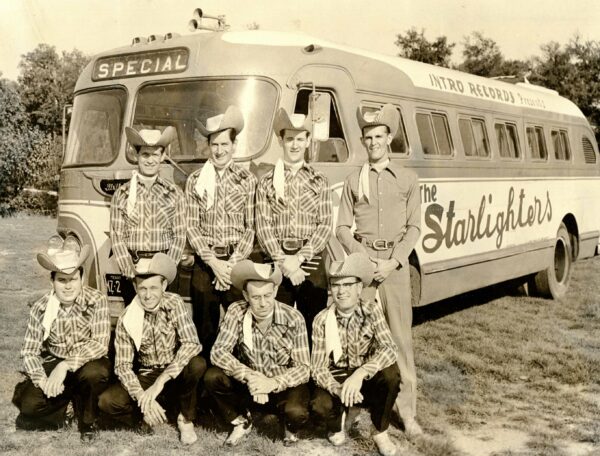

The Western Starlighters of Dallas kept western swing alive in the 1950s. Note the tiny UFOs on the band members’ heads. Image courtesy Debra Petton Bell.

Though it’s unlikely they participated in the drug culture, the dynamic Dallas gospel group The Relatives was described by Grammy-winning producer Leo Sacks as “Jesus on LSD.” Image courtesy of Matt Wright-Steel.

The experimental sounds produced by Dallas’ official Boneheads, a club founded on principles of civic surrealism, enchant or disrupt a 1951 meeting of the Dallas Ad League. Image courtesy of Dallas Public Library.

Margaret Wilson, on accordion, and Duenne Collins endure the spirited hijinx of apparently tipsy lawyers at Eagle Mountain Lake during the 1940s Texas Bar Association Convention held in Fort Worth. Image courtesy of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections.

Pulitzer Prize winning saxophonist Ornette Coleman first saw his instrument of choice when Sonny Strain and his Sultans of Swing came to play for his classmates at George Washington Carver Elementary School in Fort Worth. Entranced, he shined shoes and saved up for years to buy his first saxophone. One of many fine jazz sax players to emerge from Cowtown, he is seen here performing at the 1983 grand opening of the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth. Image courtesy of University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections.

Dallas trumpeter Hugh Fowler and his dance orchestra are seen here circa the early or mid 1960s costumed for some kind of smartypants send-up of contemporary art. Image courtesy of Gene Fowler.

Ernest Tubb spent two transformative years in Fort Worth, from 1940 to 1942, during which he morphed from a Jimmie Rodgers imitator to a founding father of the modern country-western sound. Image courtesy of Johnny Case and Tracy Pitcox.

Charley Pride first heard country-western sounds while growing up in Mississippi, when his sharecropper father would tune in the Grand Ole Opry from Nashville. Seen here performing at Fort Worth’s Panther Hall, Pride relocated to Dallas after patiently defying the genre’s racial barriers in the mid-1960s. Image courtesy of the Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

The earliest reference I could find to violinist Alfredo Casares is from 1929, when he directed the Mexican Serenaders on Dallas radio station WFAA. One program announcement described the Serenaders as “a group of talented native Mexicans, who were at one time the official orchestral entertainers for Pancho Villa….They feature folksongs of their country and play them as only real Mexicans can.” Seen here on the 1950s WFAA TV program Mexican Jamboree, Casares was multi-cultural before multiculturalism was cool, also performing with several mostly Anglo western swing groups. Image courtesy of the Dallas Mexican American Historical League.

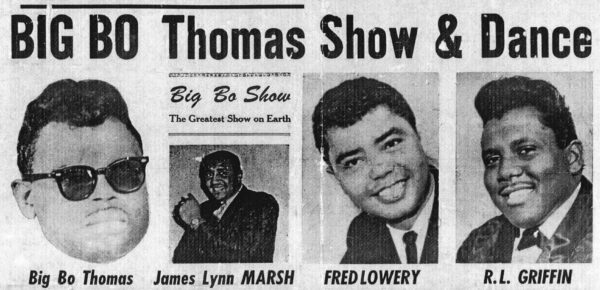

“Have no fear, Big Bo is here!” Tenor sax man and bandleader Big Bo Thomas owned Dallas clubs the Empire Room, the Peacock Bar, and Zanzibar (not to be confused with Fort Worth’s Zanzibar). He also owned his own label, Gay Shel Records, named for his daughter Gayle and son Sheldon. In 1962 he released “Big Bo’s Twist” on Dallas’ Duchess label. The “raucous disc” reportedly sold some 76,000 copies in two days. Image courtesy of Gayle Thomas.

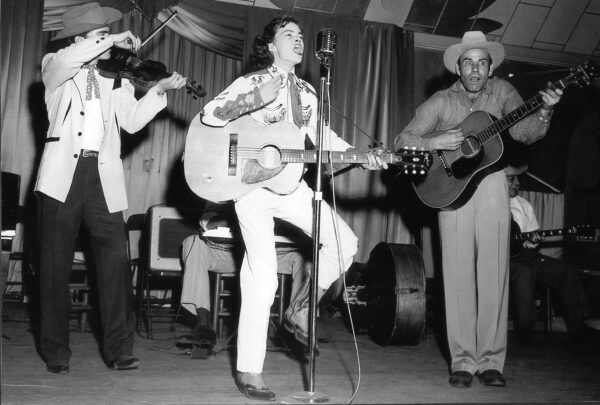

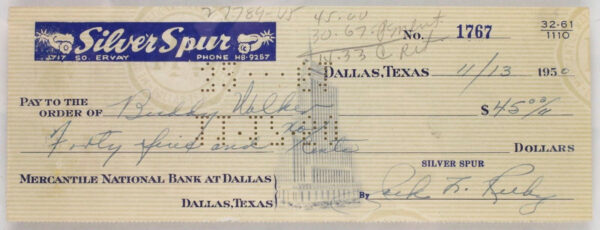

Born in a boxcar in Henrietta, Texas in 1929, Charline Arthur grew up in a family of Pentacostal gospel performers. A regular on the Big D Jamboree, she was often called “the female Elvis” for her high-energy performance style. Image courtesy of David Dennard and Dragon Street Records.

Jack Ruby owned several Dallas nightclubs before elbowing his way into history as Big D’s Greatest Enigma. It’s said that he once charged patrons extra admission to see a passed-out Hank Williams backstage at one of his clubs. On another occasion he reportedly helped walk the Hillbilly Shakespeare around a golf course in an effort to sober the star up before a performance. Image courtesy of Erv Karwelis and Idol Records.

In the 1960s unscrupulous promoters preyed on eager young DFW artists, sending them out on tour as the famous English group The Zombies. These faux Zombies, who nonetheless moved audiences with their music, are from left to right, Seab Meador, future ZZ Top rhythm section Dusty Hill and Frank Beard, and Mark Ramsey. Image courtesy of Mark Ramsey.

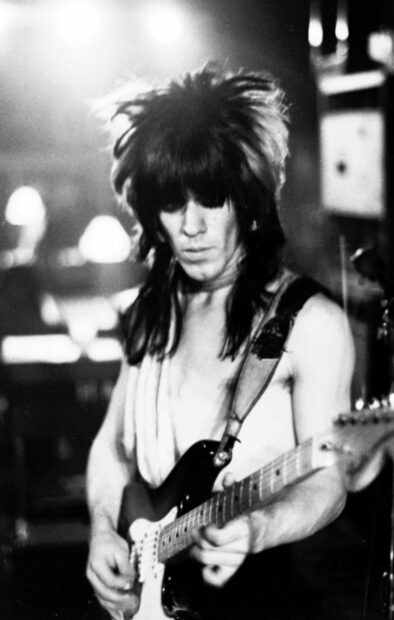

“All the girls fell in love with him that day,” wrote classmate Debbie Hedges of the time Seab Meador performed “Blue Suede Shoes” in the Mark Twain Elementary School Talent Show. Seen here as the lead guitarist of The Werewolves, a Dallas group transplanted to Manhattan, Seab lived with his wife Judy Jergins in the bohemian Chelsea Hotel, where he maintained a small shrine of books, photos, and colored candles that represented various wishes. “Seab had little rituals,” says Jergins, “things he would read out loud daily about wealth, power, peace of mind, and health.” Though he died of cancer in 1980, Meador’s guitar brilliance continues to influence Texas musicians today. Image by Dennis Recla, courtesy of Gloria Wilkes and BigD60s.

The band Felicity, seen here in Deep Ellum in the late 1960s, became regional stars in Denton and Dallas before moving to Los Angeles, where one of its members’ greatest hits compilation with a band called The Eagles became the best-selling U.S. album of all time. Left to right: Mike Bowden, Don Henley, Jerry Surratt, Richard Bowden. Image courtesy of Richard Bowden.

Metro Music – Celebrating a Century of the Trinity River Groove by Gene Fowler and William Williams is published by Texas A&M University Press. Learn more and purchase the book here.