1998 was a dawn of a new kind of Christian evangelism in the North Texas suburbs, one that fused with secular culture to appeal to headbangers, gang bangers, and goths. Wednesday nights at Hope Fellowship Christian Reformed Church in the middle of the Cedar Hill slums were a mashup of live metal music, skateboarding, and cigarette smoke. The youth pastor had a goatee and wore black t-shirts. It was mostly an audience of young boys (including me) in JNCO jeans doing ollies and slap-boxing outside. Then the metal music would spill out of storefront church and call us inside to bathe in its baptizing brutality.

Most of us left the neighborhood and the now-shuttered church long ago; we scattered. But on one night in the spring of 1998, I came across someone in this scene whose path I’d cross again 17 years later.

Onstage that night was a band called Infirmity, with a young Michael Morris on guitar. Back then, Morris was rebelling against an atheist father and clinging to something that, for him, was a line to meaning and empathy. A passionate and feverish version of Christianity played a crucial role in his evolution, as an artist and aspiring adult.

Present day, as a working artist in Dallas, Morris has turned to a kind of religious and artistic formalism, while cultivating a perhaps fanatical relationship with outdated technology, language and phenomenology.

“I exist in a kind of weird, in-between space,” he says. Locally, Morris’ work turns up in group shows in venues such as the Dallas Contemporary and DMA. “Outside of town I present in film festivals or experimental-film-related venues, and over the last several years I’ve primarily exhibited things that are performative and cinematic. I think they exist in a weird space where people don’t really know what to do with it.”

Morris is one of Dallas’ most tireless artists, and he works primarily with video and celluloid film. He’s participated in the Dallas VideoFest since 2013 and helped spearhead its offshoot the Dallas Medianale, an adventurous presentation of experimental video programming along with media performance and installation; Morris describes it as less film festival and more “hybrid exhibition.” It debuted this year at the Mckinney Avenue Contemporary. And he’s still experimenting with music, creating harsh noises and soundscapes in live settings.

“I think the space of cinema and the space of seeing a concert have a lot in common,” he says. “In both there’s a social contract and everyone acknowledges [that]… it will be both a singular and communal event.”

As a musician, Morris performs frequently around Dallas, on multi-performer rosters at venues like Crown and Harp, Pariah Studios, and Black Lodge. And as an artist he travels extensively, exhibiting in fringe film festivals. There’s been one solo exhibition of his work in DFW since he returned to Dallas from receiving his MFA at University of Illinois-Chicago. In 2012, Morris’ It’s Just Meant to Be at Oliver Francis Gallery (now OFG.XXX, founded by Kevin Rubén Jacobs) stands as the only time a gallery has taken a chance on Morris’ hard-to-commodify, hyper-personal hybrid of images and sounds.

“That was a special situation, that was part of Kevin’s vision at that point where he would turn the keys over to the artist and let you do whatever you want,” Morris says. “That was a license to do that… I thought [it] was exactly what I was looking for. Everyone stopped what they were doing and watched and took it in.”

Morris fell for film through a video class at Richland College 2004 where, he confesses, “I didn’t know what I was doing, I just knew I had to be in school.” But there he “caught a bug,” and transferred to UNT, where he decided to become a director of “strange, philosophical feature narratives; I wanted to be Fellini.” It was there he found the films of Barbara Hammer, Maya Deren, Sadie Benning, and most importantly, Kenneth Anger—artists who did radical things with the medium. “What I saw in them was the ability to make film on the same basis as you write poetry,” Morris said. “I had a real crises when I didn’t know whether I was going to pursue being a poet or being a filmmaker.”

For Morris, finding Anger was a way to deal with the creation myth’s place in his own work. “There’s a level of belief in Anger that I found very comforting,” Morris says.

“Even in his piece Lucifer Rising, there’s a direct interaction with the mystical… with something bigger than the self that really was comforting to me,” he says. “There’s a scene where there’s a woman dressed as an Egyptian priestess and another person dressed as a pharaoh where there’s a direct level of communication between them and a spiritual level of interaction with the environment, where he raises his staff and lightning strikes. And for someone who was losing his faith, that was comforting to still have this interaction with the divine, even if it was completely profane and evil.”

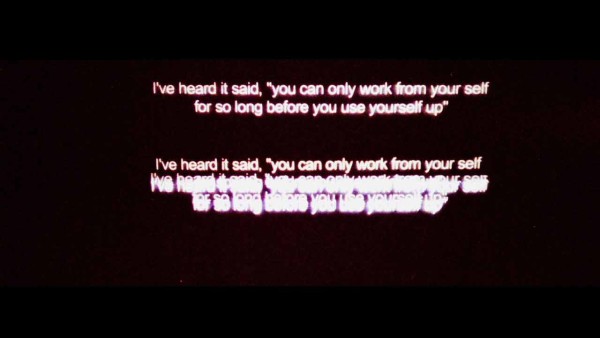

Still from “Fires” (2013), an experimental project Morris created that cross-references memory and language, and the failings of both. This is a common theme in Morris’ work.

As for poetry: language as “a linguistic system” plays an important part in Morris’ idiosyncratic narratives. He works alone on each film, building a framework similar to the way a poet builds in syntax. Language is his guide. The presentation of the work is equally loaded for Morris. “If I’m not exhibiting empathy I am at least asking for it,” he says. For him, creating an intense, all-inclusive environment evokes his experience of store-front worship centers. “There is a congregation element with performing that has a spiritual component,” he says. “And while I am critical of the power component [within religious congregations], I think it’s still a valid and important mode of experience.”

Still from “Invocations” (2008), a film on the study of spiritual belief within social structures and group-think. Morris explores these elements through re-staging first-hand accounts of baptisms and shared spiritual experiences.

In the darkness of a performance, where our minds and hearts are at their most vulnerable and malleable, Morris believes a transcendence takes place. Whether it’s for the sake of the sacred or the profane is in the hands of whoever is on stage. That power is something Morris is very conscious of when presenting his work. For him, empathy rules. “When someone says ‘What you are experiencing is God,’ it’s really convincing.”

Micheal Morris’ work is in the upcoming group show ‘Irrational City,’ opening July 3 at the Bath House Cultural Center. You can find more of his work on his website.

2 comments

Thanks, Lee, for this great article. It’s a real honor to have someone pay close attention to my work and my life. I really appreciate your treatment of our conversations, and it was a treat to realize our common paths.

Reading myself, I can’t help but want to amend certain things I’ve probably said to lots of people. I realize it may be me who doesn’t know how to categorize my own work at times, because many people in many areas have given me numerous opportunities, and it’s possible they get what I do better than I do. And for the record, only the christian version of me thought of Anger’s work as profane/evil. Clearly it was/is devotional in its own way, and at 22 the campiness of much of his work was totally lost on me.

It’s a great exercise to pick apart my own language this way. Thanks again.

I have always been intrigued by Michael Morris’ interpretations of the nature of film and film structures. The creative range in his work is without boundary, but does seem to focus on how we communicate and come to know the spiritual meanings we seek.