It’s not much to look at, but Ludwig Schwarz’s work never is. Oliver Francis Gallery’s two small rooms house a parade of deliciously underdone objects scooped from Schwarz’s prolific, thoughtful, funny world and lined up for morning roll call.

Though he appears from behind the scenes only once, in Old Medicine, as a pathetic peddler of outdated remedies, Schwarz’s character is omnipresent. Though they vary in size, shape, material, and subject, each new work is another instance of Schwarz applying Schwarz, like barbecue sauce, to new situation. Schwarz’s peddler’s pack contains an assortment of recurring autobiographical themes: junk food, professional sports, barbecue, pawnshops, and painting.

It’s a real retrospective in the narrowest sense; even the arrangement is chronological. Beautifully succinct, twenty-five years are compressed into twenty-five feet. Just as man evolved from apes, Schwarz’s timeline illustrates his progress from the elegant formal hi-jinks of Kick (1990) through rock-bottom abjection of Great Moments in Painting Number 4, into gags exploiting the surreal possibilities of commerce like The Fastest Pawn Shop Transaction in the History of the World (2002), in which Schwarz pawns valueless videotapes, then immediately redeems them. Thus ends Act I, in the Gallery’s front space, around 2005.

Act II continues, after a brief partition, in the gallery’s back room. Old Medicine (2008), the first piece after the hiatus, is the most explicit evocation of Schwarz’s fictionalized self. Props and a photograph cast Schwarz as an absurd peddler, shown walking away across a field in a sport coat, shouldering a ridiculous kitchen cabinet for a backpack. In the gallery, the cabinet acts as a pedestal displaying an unappealing selection of half-squeezed tubes of ointment and broken packs of pills. Recalling Steve Martin’s character in the 1979 film The Jerk, Schwarz’s character makes a pathetic stab at self-sufficiency, a lonely wayfarer taking his place in the long line of comic hobos.

Next up is a diamond-and-gold-encrusted toilet plunger, a one-liner’s one-liner. I first encountered this piece at the Dallas Art Fair, where it was busy deflating the precarious presumptions of value that buoy art sales. It’s a bit of wordplay, too: on Wall Street, a “plunger” is a foolishly enthusiastic investor. In the shabby Oliver Francis Gallery, the piece is more optimistic, proclaiming the chance of finding diamonds in the dustbin. The gems are small, noticing them forces a double-clutch: a sideways shift in mid-thought that is the quintessence of what’s great about Schwarz’s works, whether slow and subtle, or pie-in-the-face, as in this piece.

The folding snack table didn’t do much for me; let’s skip it. But I was suckered by the dramatic nail-tree sculpture that was next in line. Two splintery 2x4s propped on wobbly lumber legs sprout a forest of nails like St. Sebastian or a Nkonde fetish. Images of torment, overkill, and brutality are both undercut and amplified by its workaday backstory: the piece is a found object from one of the pawnshops Schwarz haunts, where it was used to test pre-owned nail guns. Men testing pawnshop nail guns are a frighteningly enthusiastic lot.

The violence of this piece is unusual for Schwarz whose work is typically anti-drama, but it serves well adjacent to a big oil-stained cardboard box titled Great Moments in Painting Number Five (2014), allowing it to assume a Juddish purity by contrast.

The retrospective ends with a capsule-shaped barbecue smoker standing like a bald midget in a blue spotlight. A round of canned applause from hidden speakers offers the smoker some schmaltzy congratulation: it stars in the show’s final video, a one-minute loop showing an aerial view of a Texas backyard. The smoker is at stage right, playing opposite a whirring air conditioner. As in many art videos, nothing happens, but the tableau has a Rube Goldberg twist: a gentle breeze wafts smoke from the barbecue over the air conditioner, where the fan pushes it suddenly upwards in an unexpected right-angled turn. It’s a latter-day romantic landscape, with Niagara Falls‘ cascades and thunder replaced by lazy mesquite smoke and air conditioner drone. Ordinary life is full of undersung marvels.

I’ve called Schwarz a comedian twice now, and it’s a role he’s certainly comfortable with, but Schwarz’s comedy is an inevitable corollary of a serious practice: the abrupt shifts in perception Schwarz triggers are inevitably punch lines.

It’s worth noting that, since 1995, Schwarz has been a prolific producer of paintings, or rather, of flat, painted canvases that struggle mightily and unsuccessfully against painting as a way of consuming artistic ideas. He’s made paintings that face the wall, paintings which can only be seen only on the Internet; paintings packed away in unopened crates; and paintings notable for their intentional unappealing vacancy. But in this show, in a most sincere gesture of respect for his ongoing project, which now seems prescient when one surveys the works of new grads from the upper-crust art schools, there are no paintings. Two pieces, Great Moments in Painting Number Four (1999) and Great Moments in Painting Number Five (2014) bookend the lacuna with accessories: Number Four is a spattered plastic drop cloth, as if from a studio floor, folded and ceremoniously adorned with empty beer cans; Number Five is the big cardboard box, open and emphatically empty.

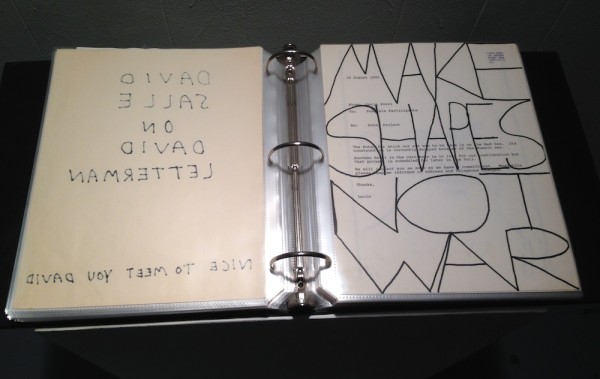

A fat binder of drawings near the door condenses the powers and pitfalls of Schwarz’s hit-and-run approach to art. The first thirty were superhumanly good: piquant, offbeat, fresh. About halfway through, they flattened out into one-liners with an occasional zinger. I thought Schwarz had hit a bad patch, but going through the binder a second time proved it was me: fatigue had burned out my capacity to appreciate Schwarz’s subtleties. Putting so many drawings together was the rare misstep that made me appreciate Schwarz’s sense of timing, and why his retrospective is, of necessity, so short and so sweet.

4 comments

Fantastic article Bill – my only request is keep the snide commentary out like “But in this show, in a most sincere gesture of respect for his ongoing project, which now seems prescient when one surveys the works of new grads from the upper-crust art schools, there are no paintings.”

Need we not forget that he was also once a recent grad from SVA…Obvious unprofessional dig.

Nothing snide about it- I meant it literally. Schwarz pioneered using video and the internet to negate paintings (while still producing them) decades ago, something younger artists are desperately pursuing today. Eli Walker being a perfect example.

Two things:

1. “desperately”?

2. Whether or not painting is present in this or any other exhibition is wholly irrelevant.

Yes, desperately, as in going to extraordinary lengths, with no hope of success. Painting, as we all know, is immortal and invincible, both satirical jabs and serious assaults are equally futile. Making them anyway is desperate.

It’s not irrelevant that a major swath of Schwarz’s output is missing from a show called “retrospective.” It’s a retrospective with an enormous, I think intentional, blind spot!