Many documentaries open with a montage: extreme close-ups and Philip Glass piano riffs cue the drama of fixed-gear bike culture or the rise of Helvetica. But when you start a Werner Herzog documentary, Herzog’s voice, speaking with fervor and sincerity is all you “see,” but so oddly dramatic you can’t turn away from the screen. Margaret Meehan’s work is like Werner Herzog’s voice.

Meehan’s solo exhibition, we were them, at David Shelton Gallery in Houston is like a documentary montage. A gallery handout explains the research behind the work. Its text, a collaboration with Meehan’s husband Noah Simblist, explains influences ranging from Mexican Cofradias to Alexander McQueen. Each reference coalesces into a message of hope through fear of the other:

“. . . at some point in our own histories, or in our current reality, we were the member of a majority that looked suspiciously at difference. But we were and are looking toward a horizon, climbing the trees, and trying to fly. We search for a way to see the bigger picture and a way out of the troubled times we live today.”

Most of Meehan’s works are made from humble materials like cloth, paint, feathers, and twigs. The matte black of the objects creates a link between them. Yet, each piece still has an independent presence that makes their solidarity unnerving. Her sculptures evoke mourning dress, political costume, dioramas, and set design. The exhibit has a suspenseful, Romantic quality as if Caspar David Friedrich had built sets for a Japanese horror movie.

One of the most compelling sculptures is where history is stored. Sitting atop a low floor pedestal, a black dunce cap leans sharply to the right. The cap simultaneously connotes shame and authority by allowing the viewer to oscillate between identification with the cap’s wearer and its bestower.

One of the most compelling sculptures is where history is stored. Sitting atop a low floor pedestal, a black dunce cap leans sharply to the right. The cap simultaneously connotes shame and authority by allowing the viewer to oscillate between identification with the cap’s wearer and its bestower.

For Meehan, themes of nature reference the sublime. In the leaflet, she says, “Nature [edges] away from the forces of political and social violence.” In many of the small sculptures wood twigs are wrapped in silk bondage rope and painted black. The limbs of these small trees reach over their pedestals and into space. They are stuck rather than dead―a purgatory until their next existence. The twigs are reaching for something greater and are only bound by human constraints.

Another work inspired by nature is Meehan’s erasure, a print of a seascape horizon. The piece encapsulates both a hope for new worlds and the anxiety of exploration. Unlike the objects, which can easily be personified, the seascape is a mental landscape for the viewer. Instantly, we are either lost at sea or heading, steadfast, to land. Like the dunce cap, the perception of power is left for us to define.

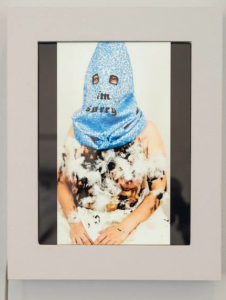

A found image of a woman from the 1950s repeated in a shape similar to wings called patterns of flight

Along with her motifs of nature and bondage Meehan constructs anonymity through repetition. Anonymity is often necessary in acts of public humiliation and public exaltation. From the KKK to Pussy Riot, donning a hood or mask allows for a special type of unification and freedom that individualism cannot achieve. In Meehan’s installation, patterns of flight, the found image of a woman is delicately and ceaselessly repeated across an entire wall. The wall reads like a shrine that simultaneously exalts and dehumanizes the person in the photo. Meehan’s conscious choice to use repetition reinforces the historical impact of societal labeling in order to differentiate, abuse, or revere.

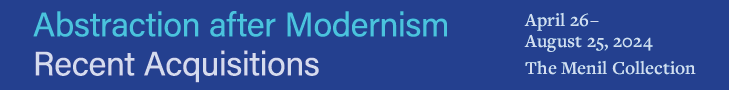

The most striking work in the show is Meehan’s video, bluebird, where a tarred and feathered woman wearing a hood that reads, “I’m sorry” nervously sings Irving Berlin’s Blue Skies. The song, written in 1926, originally referenced immigrant optimism when adapting to a new country. This video is the Herzog narration for Meehan’s exhibit―distinct, commanding, and yet elusive. Unlike the other works in the exhibit, an actual person exists beneath the feathers and mask. The awareness of the human figure is key―she directly signifies us.

The song’s lyrics are written on multiple panels of paper on wall across from the video. The paper is covered in thick black paint and each piece is pinned up by one black feather. Co-existing shame and hope in this piece conjures up a familiar darkness: independent spirit squandered by a culture of fear. Like actress Joan Crawford, shown defiantly donning a black feather shawl on the back of the leaflet, the woman in the video “is evoking the power of the natural [and] while there is a formal echo of tarring and feathering in these images…the fundamental issue is agency,” according to Meehan, explaining how sometimes the tools once used for oppression can be reclaimed to set one free.

we were them is a show rich in concept and psychological play. The only question is how the artist herself has faced the subject matter she discusses. Like a documentary, we are focused on the other. Meehan delivers a wonderfully poignant tale of our past truths, and ironically, by focusing on human history Meehan hints at her own identity. Like the woman in the photograph, slightly smiling, Meehan becomes both anonymous and all of us.

Margaret Meehan’s we were them is on view at David Shelton Gallery, Houston, through October 26.