Ashley Perez is a multitalented San Antonio-based artist who explores the complexities of memory, identity, and mental health in her paintings and drawings. I wanted to talk to her about her recent show, Common Ground, at Ruiz-Healy Art because of the unique social practice that informed her new body of work. Perez conducted field research in a number of public parks around San Antonio by talking to people about their experiences and feelings surrounding time spent in nature. Perez’s practice is unique to me because her work fosters a critical dialogue with the public well before the artworks are created, and presumably well after. Along with pursuing her artistic practice, Perez leads visual arts middle and high school programs at SAY Sí, where she engages the minds of the next generation of creatives.

Ashley Allen (AA): How did you first become interested in the nature and wildlife in San Antonio, and when did you decide that these were things that you wanted to bring into your work?

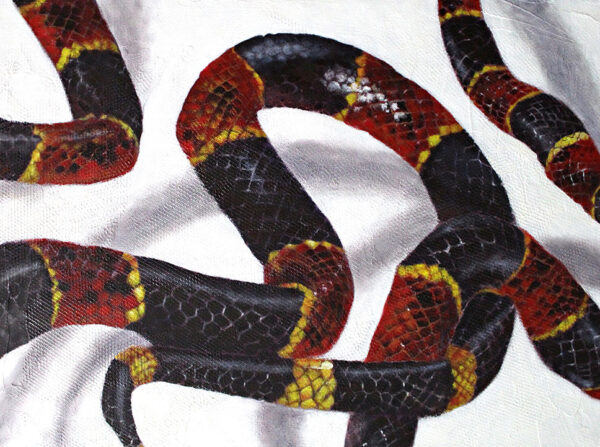

Ashley Perez (AP): I started getting into natural and local flora and fauna within the last five or six years, but honestly, I’ve been incorporating nature in my work since I was a teenager. I went to the after school program SAY Sí when I was a young person and they have a senior thesis exhibit, and in preparing for that I actually created a collection of work that incorporated African elephants and then merged them with ideas and portraits about the people I’m close with. I immediately gravitated towards the challenge of drawing and painting those animals because of their texture. But I also really appreciated the fact that they have this incredible capacity to grieve and to mourn for their loved ones who have died, and they return to grave sites over and over. That level of memory felt really human to me, incredibly relatable. And so I ended up gravitating to that cause and using it in my work, and I kind of used that recipe for the next 21 years in my work. I’ll find something in nature that I can connect with and then just springboard off of that. I think slowly I started to incorporate the things that are around me, just gaining gratitude and feeling very familiar with these animals and more connected with the place that I live. And so that started to coalesce more and more over the years.

AA: That’s really interesting, I had no idea that elephants knew to go back to their family members’ graves.

AP: Yeah, it’s unusual and they have an incredible capacity for presence and knowing their body, so another thing that they do is they’ll be aware of their weight and size, so they’ll try not to walk on anything they might crush. Obviously they’re so large that it’s such an elegant and careful way to maneuver through the world; I also appreciate that as well.

AA: Was that time in your life at SAY Sí also when you started making art?

AP: Yeah, when I was at Brackenridge High School I started to draw and paint. Or to draw a lot. And honestly you know, I don’t know how I got started with it specifically, like, no one told me to do it. But it was a great escape. The area I lived in wasn’t very safe. And there was a lot of anger and poverty around. And then a teacher saw me drawing at Brakenridge (her name is Donna Simon), she was on the board of SAY Sí at the time I believe, and she suggested that I apply. And the story kind of writes itself from there.

AA: Can you tell me a little about the new body of work that was in your recent show, Common Ground, at Ruiz-Healy Art?

AP: Yes, that work is a project based on a grant I wrote for the City of San Antonio individual artist grant. I had a lot of time to prepare and think about this work — more than a year and a half, almost two years out. I definitely wanted to do something that was connected to nature. I was thinking about wanting to do something where I talked to other people about their connection to nature. Near my house, they finished part of the Mission Reach, so having that so nearby kind of inspired the project. I decided to create a body of work that was inspired by trails within the city limits. I thought about how these are things that our city makes in order to curate natural experience. It’s not fake, but it is kind of fake. But another reason I thought it would be a good idea is that I have some health issues and I can’t get around like I used to. So I decided to focus on areas that were very accessible, meaning mostly flat places that are accessible and had a lot of areas where it wasn’t super secluded.

In contrast, I first started thinking about going for walks seriously during the pandemic. And so I tried doing that in my neighborhood and it really just didn’t work, as much as I really tried. If I walked with my dog, there’d be these loose dogs around, and it’s not nice to be chased around like that. And then if I don’t take my dog, then I am walking alone, and I want to be aware of my surroundings and where I am as a woman. You have to be aware of that to keep yourself safe. There’s a lot of men, also, on their porches, just kind of making me feel incredibly uncomfortable, a little bit leery. So I considered some of these more populated areas more friendly and more accessible to women as well. And with that in mind, I also really like seeing other families happy. It fills my cup; it gives me hope. And so with this work, I did want it to have a very positive spin and be filled with more gratitude than some of my previous work.

AA: It makes a lot of sense why you gravitated to more of those curated outdoor spaces to facilitate the type of information sharing you were hoping to find. Can you tell me about your experiences in these settings talking to people about their connection to nature?

AP: Yes, I’ll tell you that it’s difficult to do. It’s not easy for me to meet strangers, though that might be different for other people. It’s not something I feel like I’m naturally good at. Especially when people are out and about. They do not want to talk to you. It’s like when you want to be around people, but you don’t want to talk to them just because of the amount of interaction it would take to connect with your fellow man. And when I would get someone who I could talk to, or was open to talking, I think they misunderstood what I wanted from them. I think they thought that I was going to build a piece of art right where they stood. And so that miscommunication wasn’t working, and I also didn’t want to interrupt people because the whole point is that I want to know how they feel on the trail and I’m kind of interrupting their moment.

So instead, what I decided to do was set up a table at different trailheads and as people would exit, they could approach me. I had a little sign that said “free art,” and the evening before I would create a bunch of small drawings of local birds. And then when I was at the table, I drew more because I wasn’t sure how many people would come up to me. But if they were brave enough, they would be rewarded with free art. But the catch was they would have to talk to me about their experience on the trail, and this created really positive results and I was able to meet with a lot of younger people, families, and friend groups. And then it kind of evolved and there was an opportunity for them to sit and talk with me for a long time, or just casually mention some things and then run off. So it was like everybody had what they wanted.

AA: Interesting, it was like a mutual kind of interaction. I know for me, I go out into nature sometimes to get away from people, but if art was involved, I would be sold. What were those conversations like with strangers from all walks of life?

AP: It really depended on the interaction. For the most part, I would ask them to, “talk to me about your experience on the trail. What brings you here today?” I wanted to ask questions that were more open-ended because I wasn’t sure the answer I would get and I didn’t want to pose questions that were limiting. I wanted to figure out the unknown. I did the same thing on a previous project called the Forgiveness Project which was exhibited at Presa House Gallery in 2020. For that work, I interviewed women about their relationship to trust and how they dealt with forgiveness and other interpersonal situations. And leaving the questions open like that produced a variety of answers and created unexpected artwork, so I was hoping to reproduce that magic a little bit with this project, not knowing what people would say and how these interactions would inspire my work.

AA: I noticed that you use a lot of circles and curvilinear lines in this body of work. Can you talk about these decisions?

AP: Yes, the circles are new lines that I’m working with. I think here they became stronger in my work. I thought about them as time pieces, and when I don’t draw the entire circle, it creates an implied circle. They extend outside of the boundaries that I think enlarge or imply a larger composition. And it becomes interactive for the viewer in that way. I use them to move the viewer’s eye around to literally circle what I have them look at. They also interrupt the image in a way that helps the composition.

The subject matter that I choose is pretty — it’s pleasant to look at nature. By design there is beauty in it and being surrounded by it helps regulate you, because you’re surrounded by such pleasantness. Ideally you’re not being stung by mosquitoes, and because the works are so attractive on their face, (interrupting it a little bit, especially with the images I’ve created with a lot of value and texture and color), they flatten out the image and remind you that its a painting. I think that the flattening effect creates a balance and harmony in the work, as well as tension.

AA: Can you tell me a little bit about the project you’re currently working on for the city that’s inspired by the history of San Antonio?

AP: I’m really excited about it. About two years ago, I was approached by the public art department, which wanted an artist from District 3 to produce a piece of public art to put near the missions. I worked with the Mission San José Neighborhood Association and they described what they were hoping to get out of this piece of public art. In general, the task was to create something that highlights the time before, during, and after colonization. And so I consulted the American Indians of Texas on a few things, and then after some back and forth with the public art committee, came up with a design that highlights the different crops that became more frequent during those times.

The piece uses the crops as a way to highlight how diets change and how culture changes. And the design also mentions and highlights the descendants of those missions, so part of it incorporates a radial ancestral chart (the kind of chart you can fill out with your grandparents or uncles and try and get as far out as possible). It radiates and circles come out and out and those designs are put onto two giant hands, so the piece is going to be about 12 feet tall, 20 feet across, and made of metal. The work also has an element of water. We couldn’t talk about the missions without talking about the importance of water throughout time. And so again, the process was working with the community, trying to stay open, and then also letting what they’re telling me inspire my own authentic creativity. So making this piece will be similar to how I normally work, but this will be my first public art piece.

AA: Wow, that sounds awesome! There’s something to be said about the difference between static public art that doesn’t really take the place or site into account, and then the kind of public art that you’re talking about with this project for the city, and even with the Common Ground project. I think it could also be considered a kind of public art or social practice that includes human interaction and exchange. Thinking about the effect that those have on building community and engaging people in conversation, and asking questions about art and place and environment are conversations happening outside of the typical art space. So it’s really interesting to me that you use these conversations with people to inform your work instead of only having your work inform conversations within a very specific art world space. It feels like it creates a wider conversational loop.

AP: Yeah, I would have to agree. I think that’s kind of ramped up in the years that I’ve had more practice in my own career. We’ve formed a workers union at SAY Sí, and part of the reason why we decided to unionize is because we were working in this space and felt that we should have a say in what’s going on. We’re capable. We want a voice in what happens around us, and you can kind of see that reflected in this project as well as the Forgiveness Project — I want to be in partnership with the space that I’m in, out of a respect for it. And out of a trust for the people who would talk to me. And with the union, out of a trust of the workers because they work there and know that work. [Here is more information about the SAY Sí Union.]

AA: I definitely hear what you’re saying there. Speaking of SAY Sí, how do your roles as an artist and as an arts administrator and educator inform each other, if at all?

AP: They definitely inform each other. The work at SAY Sí is really challenging. I’m often tasked to be innovative and deal with complicated situations every day, but they’re creative problems and they’re with people who care about the work that they’re doing. And the students are incredibly invested in the work that they’re doing too. It motivates me, because I’ve been pushing them all day and then that echoes in my mind when I leave and go home to my studio. As an educator, I’m always barking at them to be intentional with their work and encouraging them to be authentic. To challenge themselves, while also expressing that creative need that comes naturally.

I try to promote positive messages to drown out what we all know is this maybe toxic voice inside you that might be giving you a negative sense of what it means to be a creator. And, you know, we all have that in our head, and teaching kind of pushes those negative voices away. It’s definitely a lively place and a lot of the kids are funny and strange, and they enjoy being around that sort of energy. And while it is draining to give a lot of my energy to that work, it does also fill my cup at the same time because of that energy and that engagement the students produce.

AA: It sounds like both challenging and rewarding work in the best ways. I’m curious, what advice do you give young artists?

AP: My advice to a young artist would be like advice to my old teenager self. I would ask them to learn to write and to talk about their work. That is something I feel like I’m still learning. And to read and listen to what others write and how others talk about their work. I encourage young artists to respond to their emails and be known as a reliable person, because you can do your art and it will be great, but if you respond to your email, people will give you an opportunity to spread your artwork and you will get that good word of mouth. I also encourage them to find a mentor — it’s important not to silo yourself. And the mentor doesn’t even have to know that they are your mentor. There are so many unwritten rules in this field and I find that I’ve been able to go a lot further with the assistance of artists who are creative people and have been able to show me the ropes along the way. But you have to be aware that you don’t know something that they do. But gravitate towards that and lean on the community in that way. And, last but not least, is to keep a sketchbook! I was working in my sketchbook when that teacher encouraged me to go to SAY Sí.

Ashley Perez: Common Ground was on view at Ruiz-Healy Art in San Antonio from January 10 – February 3, 2024.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.