I recall how, as a young girl visiting my relatives in Stamford, just north of Abilene, I was enthralled by my late grandmother’s collection of porcelain bud vases. These 1950s containers were formed as small bust sculptures of fashionable ladies, their updos crowned with fancy hats, the tops of which were open to allow for the placement of flowers. There, in that rose-colored and rarely used parlor, I would sit for long stretches, admiring shelves full of these beguiling figurines. Their faces were turned demurely away from mine, thickly-lashed eyes gazing downward or — more likely — closed altogether. They were to be seen and not heard, and certainly not touched: mute and immutable.

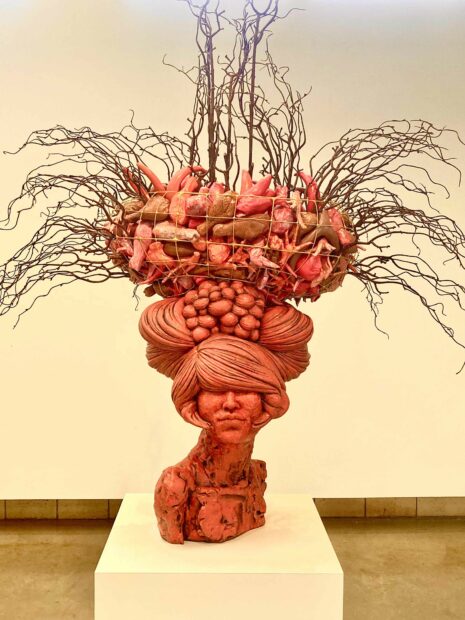

I could not help but think of those porcelain women-vessels as I moved through Misty Gamble’s Of Flesh and the Feminine,” currently on view (through October 28) in the Helen Devitt Jones Studio Gallery of Lubbock’s Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts. Gamble’s ceramic works are larger-than-life bust figures of women; their tresses are woven into elaborate coiffures, atop which sit great headdresses heaped — where flowers might otherwise have been — with ceramic chicken drumsticks, wings, feet, and also antlers.

Feeling like Alice in Wonderland after she consumed the contents of a “drink me” vial (or a piece of mushroom or teacake, depending on where we are in the story), it was as if I’d shrunk to find myself wandering among the cousins of my childhood bud vases. As with my grandma’s 1950s lady heads, Gamble’s women are decadent and likewise rendered sightless, blindfolded (and sometimes gagged) by their own tresses. The viewer is free to gaze at them without the discomfort of having them stare back (with the exception of one cheeky exposed eye in Russian Orloff, that is). The experience of treading among them is, nevertheless, eerie: despite their differences, these figures are unnerving in their similarities, their homogeneity. Whereas the 1950s versions would have been crowned by flowers/life, Gamble’s figures are capped with carcasses/death.

Gamble’s oeuvre, in general, encompasses themes of excess, consumerism, feminism/femininity, and indulgence. Of Flesh and the Feminine deals, specifically, with “the intersection of feminism and environmentalism and looks to the relationship between human animals and non-human animals.” Her theoretical framework is rooted in the ground-breaking but controversial 1990 book The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, by feminist-vegan activist Carol J. Adams. Central to Gamble’s series of works is Adam’s premise of the “absent referent.” Adams explains, “Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes… The function of the absent referent is to keep our ‘meat’ from being seen as having been someone.” She equates this unanchoring of meat from its animal source to the objectification of women, as they are reduced to disembodied, free-floating fragments, ready for consumption.

In Gamble’s exhibition, we are absorbed with abundance, easily connecting woman-meat-food examples from popular culture: Lady Gaga’s meat dress, Carmen Miranda’s 1940s cornucopia-headdresses filled with fruit, double-entendre food-based emojis, “cheesecake” calendar pinups, and even Margaret Atwood’s novel The Edible Woman. To remind us of what she sees as the parallels between violence against animals and against women, Gamble’s title for each work is a different breed of poultry. In keeping with her themes of consumerism and decadence, she represents, not surprisingly, rare and expensive varieties of chicken — those bred for their stunning physical features.

For example, the title of Ayam Cemani — which is given to a luxuriant jet-black figure whose head is loaded with faux hair braids, fake flowers, metal, and cast ceramic chicken parts — also references a rare variety of fowl hailing from Indonesia. This breed possesses a dominant gene that results in fibromelanosis, yielding a bird that is entirely black — feathers, beak, the inside of its mouth, comb, organs, and meat. According to Tasting Table, this chicken is a rare, much-prized one, the “Lamborghini of poultry.” It is a breed to which certain mystical properties are attached, including the restoration of male virility — it is simultaneously sexy and edible.

Many of the chicken varieties for which Gamble has named her works possess dramatic physical features related to their plumage, which may be likened to the figures’ elaborate hairdos. There is Partridge Plymouth Rock, known for its striking feather pattern; Mille Fleur (thousand flowers) Belgian d’Uccle, with its gorgeous plumage; and Polish Frizzle Bantam, whose fuzzy down overtakes and masks its eyes.

There is also Russian Orloff, a tall chicken named in honor of the Russian statesman Count Orlov, and which is possessive of a strong stamina for withstanding harsh winters. Gamble’s sculpture by this name is a frigid gray woman with pompadoured hair that’s topped with a bounty of poultry parts and antlers. All of these are encircled by a gold-tasseled hat-basket, recollecting a kokoshnik, a traditional Russian headdress that designated social and marital status. It is no wonder, too, that this bonnet’s name comes from the old Slavic word kokosh, meaning “hen.”

Gamble’s installation immerses the viewer in consumption. By conflating her female figures with disembodied poultry parts, she parallels the steps of removal that one must undertake to kill and eat an animal with those that society or an individual must adopt to commit violence against or to objectify women. In this way, her work functions as a visual manifesto of eco-feminism, one that insists that the viewer attend to how, what, and who we consume.

Misty Gamble: Of Flesh and the Feminine is on view at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts in Lubbock through October 28, 2023.