How do you approach a work of art? Do you notice how it shifts and changes as you get closer to it? Are you aware of the space it is in and how that colors your experience? What about the artwork draws you in and what repels you? Do you consider how your body responds to the work?

Mona Hatoum does. I recently had the opportunity to talk with her at Ruby City in San Antonio and she explained, “We experience the world through our senses. We respond to everything visually first, and then through the body, and then we start rationalizing what it means… so I like to have [the viewer] be either attracted or repulsed or somehow have them experience the work through their body first… rather than it being just an intellectual stimulus. I want [my art] to be working on all those levels, the physical, the mental, the emotional, the spiritual as well. I want a rich experience… And the successful works are those who do that, who maybe go through a transformation when we look at them.”

Since I first encountered Hatoum’s work, in the early 2000s, I thought of it solely as installation or sculpture. But, for an artist whose practice is rooted in performance art, it isn’t surprising that beyond the objects she creates, Hatoum is always considering the viewer’s phenomenological experience. I’ve only recently begun to formally study phenomenology, and two decades ago when I came into contact with Hatoum’s work, while I didn’t have the vocabulary to speak about it, I did clock its inherent visceral effect. When I was younger, studying art, I saw very little of myself represented in the art curriculum and collections of museums, and though culturally Hatoum and I are quite different, in other ways I found a kinship with her art: partially as a woman working in a traditionally male-dominated art world, but also in her approach to materiality and her blending of “soft” materials, like sand, cotton, household objects, and “hard” materials, such as steel and wood.

The first piece I saw by Hatoum was her 1994 kinetic sculpture + and –, on view at the Rachofsky House in the early 2000s when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Dallas. A three-inch-tall nearly 1-foot-by-1-foot box, it is small, simple, and unassuming. The box contains a thin layer of sand that is constantly being simultaneously raked and flattened by a motorized metal arm that is stretched across the piece, spinning to create a circular pattern. Perhaps it is just my memory of the work, and the singular, out-of-body experience I had with it, but I recall it being silent as the metal arm toiled on, forever drawing lines in the sand and forever erasing them in the same motion. I was mesmerized by the sculpture — both by the surface-level simplicity of the materials being used, and its deeper poetic underpinnings.

Mona Hatoum, “+ and -” (edition 9 of 14), 1994, hardwood, steel blades, electric motor, and sand, 3 x 11 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches. The Rachofsky Collection.

As I’ve returned to + and – over the years, with new perspectives and experiences, the piece continuously changes. When I was a young adult and seeing the world through idealistic eyes, I thought it was about balance, equilibrium, and harmony. Through a more jaded, world-warn outlook, it reads as futility and the inescapability of work in our lives as time marches on, indifferent to the individual. Yet, even more recently, at the beginning of this year when I encountered the work at the Dallas Museum of Art as part of the Movement: The Legacy of Kineticism exhibition, when in conversation with Ricci Albenda’s video, Panning Annex (Albert), + and – brought about new considerations related to destabilization and restabilization. Regardless of the thoughts that the piece evokes, it has always come with a kind of calm and acceptance. I can stand in front of it and feel my heartbeat and breathing slow.

Of course, the work encompasses all of these things and more. Hatoum told me, “For me, it’s yin and yang, positive/negative, constructing/destroying, it’s cycles… cycles of any kind, cycles of nature, cycles of war and peace, cycles of life, all these things… but it came from getting exposed to readings of Eastern philosophy… [learning about] the forces of nature and how they always work with and against each other. You can’t have day without night, you can’t have light without darkness.”

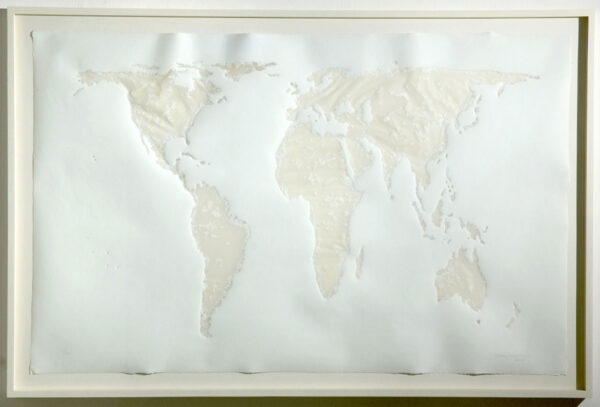

It was also at the Rachofsky House that I first encountered Hatoum’s Projection, a handmade paper piece depicting the Gall-Peters projection of the world, a map which seeks to correct issues of distortion in the commonly used Mercator projection. Made of white cotton and a thin layer of abaca, the work presents the continents as translucent debossed forms surrounded by a white ocean. The piece was created with handmade paper during a residency Hatoum participated in at Rutgers University, specifically working with their printmaking department. Much like + and –, there is a quiet beauty to Projection, along with the potential for a more powerful reading just below the surface.

The piece at once speaks to the political nature of maps and representation and hints at the potential fate of the world due to climate change. The Mercator projection, which dates back to 1569, is the map that many of us in the U.S. and beyond are familiar with, but it has been criticized for its inaccurate proportions, which seem to prioritize the United States, Europe, and Asia, effectively minimizing Africa and South America.

The Gall-Peters projection, though also flawed, because any flat representation of a three-dimensional object can never be completely accurate, seeks to correct some of the issues in the Mercator projection. Hatoum’s use of this map is a reminder that the world is not always what it seems, that what we know about places and objects is always tinged by our own perspectives, and that borders and dividing lines are rarely representative of reality. And ever so subtly, with the receding of the continents into the depth of the white space around them, Hatoum reminds us of the impermanence of our situations: that the oceans may rise and things may shift even for those of us who feel secure in the place we call home.

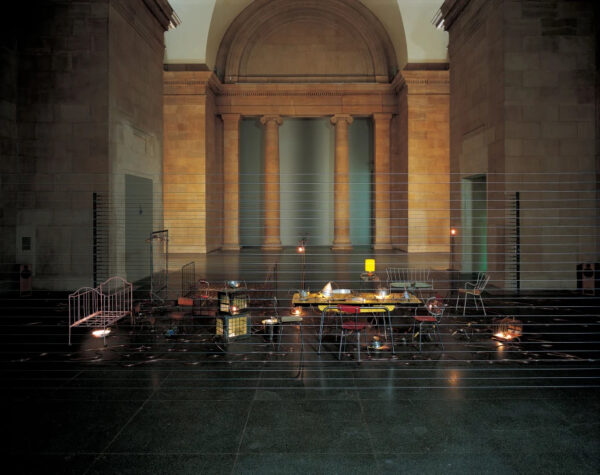

And home is a major theme in Hatoum’s work. Earlier this month I attended an opening reception at Ruby City for the organization’s new exhibition, Water Ways. Alongside works from the institution’s permanent collection, the show features two new acquisitions, including Hatoum’s 2006 piece Mobile Home II. The work features an array of household items, such as chairs, tables, handkerchiefs, toys, and luggage, set along wires between two steel barriers.

Mona Hatoum, “Mobile Home II,” 2006, furniture, household objects, suitcases, galvanised steel barriers, three electric motors and pulley system,

46 3/4 x 86 1/2 x 236 1/4 inches. © Mona Hatoum. Courtesy Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

From across the room, Mobile Home II is reminiscent of an oversized bed, with the steel barriers acting as a headboard and footboard and the wires between them creating an implied surface. I first narrowed in on the handkerchiefs hung on the wires with clothespins, and was immediately brought back to memories of my childhood — seeing my mother and grandmother hang clothes out to dry in the backyard on clotheslines stretched between two metal T-shaped posts. As I approached the work I realized that the furniture and objects on the ground were also connected to the barriers via wire and that all of the wires were in motion, moving the objects together and apart, like an ebbing ocean.

Mona Hatoum, “Mobile Home II” (detail), 2006, furniture, household objects, suitcases, galvanized steel barriers, three electric motors and pulley system, 46 7/8 x 86 5/8 x 236 1/4 inches. Linda Pace Foundation Collection, Ruby City, San Antonio, Texas, © Mona Hatoum.

As I investigate the various objects that make-up the work, my mind wanders — the pale yellow child’s chair is painted a similar color to one my daughter had a decade ago; the bunny toy hanging by its ear from a wire reminds me of feverishly washing my children’s toys and hoping they would dry before bedtime; the inflatable globe dancing precariously on the wires draws me back to Hatoum’s Projection; and on and on.

Somewhere in the midst of these personal reflections I’m pulled back to reality as I recognize the metal structures that contain the work are police barriers. These soft, sentimental moments swirling in my mind become tainted by the hint of state violence related to acts of migration. The barricades bring to mind detention centers, border walls, and other physical and legal barriers created to restrain and restrict people when they are at their most vulnerable. Being in San Antonio, a predominantly Latino city just two hours away from the U.S.-Mexico border, it’s hard not to consider the piece in the context of the ongoing violence against migrants and refugees seeking to cross into the U.S.

Hatoum and I speak about the title, Mobile Home, which is a play on words. The appearance of the piece does not directly reflect the object we know as a mobile home; instead, the title speaks to the idea of home as a place that is ever-changing. Hatoum explains, “For me it’s about a kind of flux of population… constantly in flux… moving across borders or between borders and this kind of feeling of precariousness or unsettled… whether [people] are being relocated because of war, conflict, or even natural disaster. It could be all of the above, and it’s interesting it could be placed in any place and it could be relevant. Like of course, I wasn’t thinking about the Mexican border here, but it’s very relevant as well. I like to keep [my work] very open to interpretation, so you bring your own reading to it depending on your own experience.”

Mona Hatoum, “Untitled (Baalbeck Birdcage),” 1999, wood and galvanized steel, 122 x 117 x 77 1/8 inches. Photo: Ansen Seale.

This is neither Hatoum’s first time in San Antonio nor her first time working with a space connected to Linda Pace, the artist and art patron who founded Artpace and Ruby City. Hatoum spent the summer of 1999 as an artist-in-residence at Artpace, where she completed three works, Home, Isolette, and Untitled (Baalbeck Birdcage). Each of these pieces speaks to Mobile Home II, creating a connection between Hatoum’s time at Artpace and the newly acquired work by Ruby City.

The physical form of Untitled (Baalbeck Birdcage) is reverberated in Mobile Home II, via the steel bars and the rectangular shape of the latter work’s base. The three wire spheres that comprise Isolette, are echoed in one of the objects, a small bird carrier that Hatoum refers to as a “bird taxi,” which hangs on one of the wires of Mobile Home II.

Mona Hatoum, “Isolette,” 1999, aluminum and galvanized wire, 25 x 31 inches diameter each. Photo: Ansen Seale.

Mona Hatoum, “Home,” 1999, wood, galvanized steel, stainless steel, electric wire, computerized dimmer controller, amplifier, and speakers. Photo: Ansen Seale.

And in Home, we see a fence of parallel wires, which in this case act as a protective barrier to the remainder of the installation, and are reminiscent of the wires moving the furniture and objects in Mobile Home II. Hatoum mentioned Home was the first in what could be seen as a three-part series related to the idea of domesticity. Here, household objects have been electrified, transforming the typically inviting, useful, and familiar into a dangerous assortment that cannot be approached.

Mona Hatoum, “Homebound,” 2000, mixed-media installation with kitchen utensils, furniture, electric wire, light bulbs, computerized dimmer unit, amplifier and speakers. Installation view at Duveen Galleries in Tate Britain, London, 2000. Photo: Edward Woodman. Courtesy of the artist and White Cube.

Home then led to the creation of Homebound, for an installation in the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain. The work was an expansion of the ideas in Home and included a larger assortment of objects such as bed frames, chairs, hanging racks, and more, all electrified and placed behind a tall wire fence. In 2005, Hatoum created Mobile Home, which uses the same visual language as Home and Homebound. The wires are still present, but rather than creating a barrier around electrified furniture and objects, they connect the objects and set them in motion. The following year, Hatoum made Mobile Home II for the 15th Biennale of Sydney.

The two works are incredibly similar, but are almost entirely made up of different objects. There is one object that is nearly identical — a small toy bunny. Hatoum mentioned that she and a friend found the pair of rabbits at a market and each purchased one. She used the one she bought in the first Mobile Home installation, and when she decided to make Mobile Home II, she felt it was necessary to include the bunny again. So, she reached out to her friend, who gladly offered it for the work. It’s telling that Hatoum put such significance on having this item in both pieces, and I think it goes back to the phenomenology of the work. Among the various objects that make up Mobile Home II, the bunny plays an important role. It is a small, cuddly creature that immediately conjures thoughts of childhood and the vulnerability of young children during the process of migration.

Mona Hatoum, “Mobile Home II” (detail), 2006, furniture, household objects, suitcases, galvanized steel barriers, three electric motors and pulley system, 46 7/8 x 86 5/8 x 236 1/4 inches. Linda Pace Foundation Collection, Ruby City, San Antonio, Texas, © Mona Hatoum.

It’s this attention to objects and their associations that permeates Hatoum’s work and makes it so incredibly powerful. Across her oeuvre, themes of movement, changing borders, comfort and disruption, and security and danger play out through a combination of mechanized and natural objects and soft and industrial items that dialogue with one another. Hatoum is able to tap into a wealth of emotions and memories by referencing familiar objects and placing them into surreal scenarios. This type of juxtaposition at once captivates and disorients viewers, turning what might otherwise be deemed sculpture into a performative act with the audience.

Mona Hatoum’s work is on view inWater Ways at Ruby City in San Antonio through July 28, 2024.