Ilya Kabakov, an ex-Soviet artist based in New York, known for his collaborative room-sized installations, died Saturday, May 27, 2023.

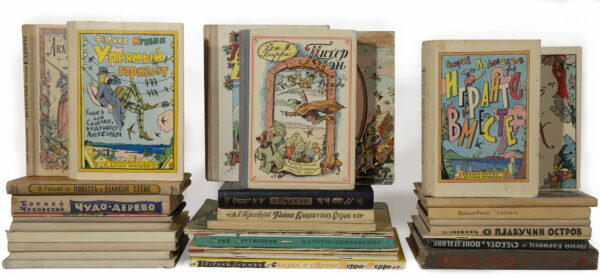

Mr. Kabakov was born in 1933 in Dnipro, Ukraine (formerly part of the Soviet Union). As a young adult, he studied graphic design and illustration at the V. I. Surikov Art Academy in Moscow. In 1959, Mr. Kabakov joined the official Union of Soviet Artists, a trade union comprised of people working in various visual arts fields. His membership in the union provided him with a studio, a salary, and work as a children’s book illustrator. Ultimately, he completed over 100 books in the style of Socialist Realism, the official style of the Soviet Union between the early 1930s and 1991.

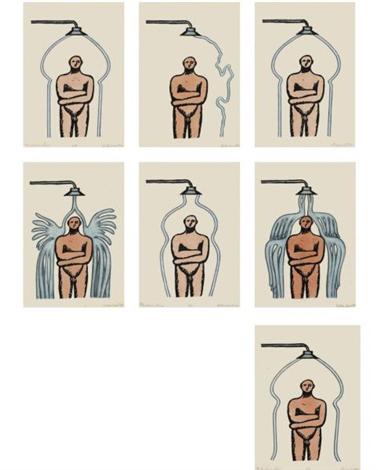

In 1965, Mr. Kabakov exhibited his work Shower Series in Italy, which marked the first time he showed abroad. The set of seven lithographs depicts a nude male figure standing beneath a showerhead, whose water inexplicably moves around him in various ways rather than washing his skin. Because the series was seen as a critique of Soviet culture, he was no longer allowed to practice and began working under a pseudonym.

Ilya Kabakov, “Untitled (7 works from the Shower series),” 1974, lithograph and colored pencil, 8.5 x 7.4 inches.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Mr. Kabakov was a leader among the Sretensky Boulevard Group, an informal association of creatives who were working outside of the Soviet art system. This group was the precursor to the Moscow Conceptualism movement, which as its name suggests, was more concerned with ideas than the physical form of an artwork, and was influenced by the conceptualism that arose two decades earlier in Western Europe. Other important members of the group included Eric Bulatov, Boris Groys, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, Andrei Monastyrsky, Viktor Pivovarov, Dmitry Prigov, and Lev Rubinshtein.

The artists would hold seminars, readings, and exhibitions, and would travel out of town to engage in “Collective Actions,” a type of group performance art. One such collective action took place in a snowy field, with instructions that read, “Upon reading this instruction turn and stand facing the forest in the direction where the rope runs. Then at command start yelling “Pull!” as loud as possible, until we start pulling the rope. Collective actions.”

Dina Vierny, Parisian gallerist and former model and muse to French sculptor Aristide Maillol, met Mr. Kabakov and other Russian artists when she visited Moscow in the early 1970s. She smuggled works by the artists out of Russia for the 1973 exhibition Russian Avant-Garde – Moscow 73, held at her namesake gallery. In 1985, Mr. Kabakov had his first solo exhibition at her gallery. In 1987, when Mr. Kabakov left Russia, Ms. Vierny provided a studio for the artist to use. In 1991, that studio is where he created The Red Wagon and the site-specific installation In Community Kitchen.

In 1988, Mr. Kabakov began working with his niece Emilia Kanevsky (née Lekach), whom he later married. Since the duo began working together, all of the work they created was collaborative.

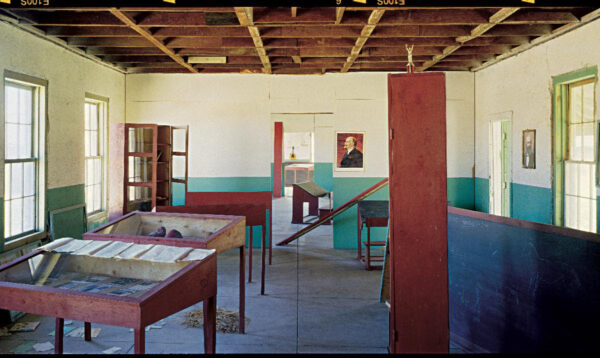

In 1991, Mr. Kabakov met Donald Judd in Vienna. The following year, Mr. Judd invited Mr. and Mrs. Kabakov to visit Marfa. In 1993, Mr. Kabakov gifted School No. 6, a multi-room installation that fills an entire building, to the Chinati Foundation. The installation is filled with remnants of a schoolhouse — posters, flags, chalkboards, chairs, and desks. Everything is in shambles, which gives an ominous feeling that something disastrous has happened in the space.

Ilya Kabakov, “School No. 6,” 1993. Photo by Florian Holzherr. © 2023 Ilya Kabakov / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In a 1994 interview with Robert Storr, then the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, Mr. Kabakov noted, “When I first came to Marfa, my biggest impression was the unbelievable combination of estrangement, similar to a holy place, and at the same time of unbelievable attention to the life of the works there. For me, it was like some sort of Tibetan monastery; there were no material things at all, none of the hubbub of our everyday lives. It was a world devoid of all trivial and banal existence — a world for art.”

In 2003, to mark the ten-year anniversary of School No. 6 and Mr. Kabakov’s 70th birthday, the Chinati Foundation published a selection of letters written to the artist in its annual newsletter.

Mr. Kabakov’s work has been in major exhibitions across the world, including Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Paintings About Paintings at the Dallas Contemporary (2021), Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and Tate, London (2017–18); Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Retrospective at Garage in Moscow (2008); Retrospective at Kunstmuseum in Bern (1999); The Palace of Projects (with Emilia Kabakov), organized by Artangel, London and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid (all 1998); the Whitney Biennial (1997); the Venice Biennale (1993); and the Sao Paulo Bienal (2010 and 1996).

Mr. Kabakov’s room-sized installations that illustrated the worlds of fictional characters echoed the realities he experienced while living in the Soviet Union. Throughout his artistic career, Mr. Kabakov’s work has been seen through the lens of anti-Soviet political work. Though, in a 2018 article in The Guardian, Mrs. Kabakov insists that the work is more universal. She explained, “It is about suffering, fear, the tragedy of man…”

According to Mr. and Mrs. Kabakov’s website, “A public memorial service will follow in several weeks. In lieu of flowers we ask that charitable donations be made to the Mattituck/Laurel Public Library or the Ship of Tolerance/Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Foundation.”