In 2022, Arts Fort Worth announced its new Emerging Artist Residency Program. The program provides one artist with a non-residential studio space at the arts center for 12 months, a monthly stipend for materials, and arranged studio visits with established local artists and arts professionals. The program culminates in a solo exhibition. North Texas-based artist Sarita Westrup was selected as the inaugural participant in the program. The work she created during the residency is now on view in her solo exhibition, The Tension of Connection, at Arts Fort Worth through April 1, 2023.

Installation of “The Tension of Connection,” featuring in the foreground, “Presence,” 2023, reed, mortar, metal, paint, 36 x 10 x 30 inches

When planning for the exhibit, Westrup wanted to include a variety of sculptues and works on paper to show her different processes. She primarily works as a fibers artist and works sculpturally with basketry, and is known for her graphic handwoven wall sculptures that suggest tunnel-like forms of movement with moments of concealment. During this past year in the residency program, Sarita started to paint as well, creating life-sized sketches of her sculptural work.

Each piece in the show is, predominantly, a meditation on movement, migration, contact, and boundaries. Westrup grew up in the border town of McAllen, Texas and identifies as mixed Mexican descent. With some family members still living in Mexico, she used to cross the U.S.-Mexico border regularly. Now living in Dallas, Westrup thinks about people who have to cross the border daily and how that’s a repetitive process in their life. She also acknowledges the treacherous migration routes that can be cyclical for many people: living in the U.S. for a little while, then returning to their country of origin, to only later come back to the States. These cycles inspire and inform the many looped forms in her show. Having dealt with the idea of a border line in her past work, Westrup likes to imagine the ways that line can be manipulated: it can be twisted, bent, molded, erased, etc.

Many of her sculptural basketry forms are made from reed and coated in mortar. The mortar not only stiffens the material, but gives her pieces a cement-like appearance. For Westrup, that surface texture references the built environments along border checkpoints (where people passing from one country to the other are inspected and allowed or denied passage). She then coats the sculptures with paint and graphite, which is a surface treatment often used with metals, and adds a visceral texture similar to that of the border wall and fencing. Overall, the works in this show translate Westrup’s memories of the natural and built environments she encountered growing up by the Rio Grande Valley of the South Texas-Mexico borderlands. After seeing the show, I had a chance to catch up with Westrup and talk to her about the work.

Leslie Thompson (LT): Is this YOUR first time to participate in a residency program?

Sarita Westrup (SW): It is my first residency.

LT: In what ways was this residency important for you and your work? Did you have any expectations or goals going into the program?

SW: This was the first year (because of the residency) that I could quit my part-time job, and I could just teach workshops and then focus on making the work. [Having more] time was a huge thing for me. I was expected to work 16 hours a week, have 2 public engagement events, and then complete it with the solo show.

I was pretty nervous about the solo show part, but I thought this would be a good experience for me. I had been racking my brain: how can I use this to help propel me forward so that my life can have a big shift? Because I didn’t want [my art-making practice] to just be this thing that I’m balancing with my life. I want it to be my life. How do I make my art the generating force for my purpose and my income? So the residency has really helped me realize that.

It was a perfect fit. Systemically, residencies don’t really take into account whether or not an artist has a family or a long-term partner, because a lot of them don’t come with a stipend or housing that can cover those needs. And I do have a life partner and a dog — I have a small family. And this is the perfect first residency to accommodate my life. And that will hopefully propel me to other residencies that are either shorter term or fit into my life.

LT: You mentioned that this residency includes a workshop component, engaging the public, and I know you have taught a lot of basket weaving workshops over the years. What do you enjoy about introducing people to the craft?

SW: I really enjoy being a teaching artist. It’s an important part of how I identify as an artist. I really enjoy seeing if it’s something that can be part of the participant’s creative life. I enjoy watching sparks happen. Or even when they’re really frustrated, I give them space and let them bounce back and move past the short-term struggle — that’s a really nice moment to acknowledge.

And it’s a time to create community. I try to make every class be a place for dialogue and conversation. It’s easy to be anonymous in your everyday life. Or not speak to a stranger or share something with a stranger. If I can create a short time and space for you to engage with someone else, meet a new friend, share your opinion, and then also work on your hand skills and walk away with a functional object that you problem solved — that’s a really good afternoon! For me, it’s about generating that type of positive learning environment.

LT: I know that to be true because I’ve taken one of your workshops. I first met you in 2013, and ever since I’ve always thought of you as a weaver of sorts. And particularly, when I think of your work, I think of basketry. My only direct relationship to baskets is having taken a 6-hour basket weaving class at Oil & Cotton (and I proudly display my star basket in my house), but you obviously have a much deeper connection with basketry. Tell me, when you look at a basket, what do you notice? What is it about basketry that speaks to you?

SW: At the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, during their show [Speaking with Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography], there was a piece woven out of transparent paper and x-rays of Indigenous children’s remains buried at the Carlisle Indian Boarding School [Remaining a Child by Shan Goshorn]. It was woven into paper that had written and identified all of the people’s names. It was in the pattern of a traditional Cherokee basket. I was like, “wow!” I love how all of this can coexist to create this greater meaning. And within a structure that has a lot of cultural origin and meaning. I found it very exciting. How things are held together with tension is very exciting to me. I feel like the basket in my show [Presence] speaks to the idea of a basket embracing and holding, it’s something I’m always attracted to and respond to. And that you can make them out of anything!

LT: Let’s talk about materials. You were trained as a weaver, having earned your MFA in Fibers from the University of North Texas in 2012 (a shout out to your mentor Ann Coddington Rast). You’ve learned other skills, like net making from Pat Hickman, the fiber artist. And from Pat you also learned an origin story of the craft (from Hawaiian mythology): the net symbolizes the sky, while the knots are the stars. I think that’s a beautiful metaphor, and I notice that the materials you use also speak to different metaphors or relationships within the work, like how nets are made from tension, and your work speaks to the tension found along the US-Mexico Border. Your work also features materials like wire and ixtle (or Tampico plant fibers). Can you talk more about the materials in the show and what meanings they have for you?

SW: The reed is a go-to. It has the tradition of being part of American craft basket weaving, geared towards hobbyists. It’s very flexible and easy to work with. I like to push it out of its hobbyist realm by coating it with mortar, that for me references the domestic sphere and repair of the home. But it also emulates cement, which for me is referencing the built environment along border checkpoints that separate people from the Rio Grande River.

Any kind of wire, for me, is an extension of fencing. I enjoy using it to make nets or to wrap with. The spray paint and graphite [on the surface of the baskets] is referencing metal working, and emulating metal surfaces.

The ixtle I learned from taking a brush-making class. In English, it’s called Tampico fibers. When I first touched it, I thought, “this feels familiar.” Its name in Nahuatl is ixtle. It’s from an agave plant. A lot of purses and woven elements are created out of agave in Mexico, so I was like, “oh, I’ve touched this before.” For me, it’s something I’m still playing with, but I enjoy the relationship the material has with brush and broom making — brooms being a symbol for clearing or cleansing the space, or rituals like sweeping. In some of the works in the show, like Border Brush, I think about if the border is a line in the sand, I can erase it with this brush. I can sweep it away. Or Border Brush II, the shape for me is referencing the idea of when you hear people are crossing in the most dangerous places in the desert and they need to conceal their footprints — this is something you can use to conceal the footprints and sweep them away.

[Another material is] cochineal ink on watercolor paper. It’s pink. It’s adding some vivacious color to the show. It’s a natural material. Cochineal is the bug that eats the prickly pear cactus. It’s native to Indigenous processes of dying cloth and yarn. It has a lot of meaning about place in the paintings.

Sarita Westrup, “Border Brush,” 2022, reed, ixtel, thinset, cement, metal, wood, milk paint, paint, graphite, 17 x 13 x 5 inches.

Sarita Westrup, “Border Brush II,” 2022, reed, ixtle, mortar, metal, paint, graphite, 23 x 21 x 5 inches.

Sarita Westrup, “Movement III,” 2023, Cochineal ink, citric acid, gesso, watercolor paper, 11.25 x 13.5 inches.

LT: Right, so you have some paintings in the show, which creates a really interesting dialogue with the baskets. Can you share a little more about your painting practice? Is it separate from your sculptural pieces, or does one inform the other?

SW: There’s two different ways I approach the paintings. A lot of the black and white paintings are logistic drawings of the pieces that I intend to make. Or they are me thinking through ideas or desires of things to make. When I’m painting them, I’m thinking about how I’m going to weave this, weave wedges to create curves. They’re very functional for me.

The cochineal paintings are the opposite. They were done after many of the sculptures were finished. So they’re little contemplations of the finished sculptures.

LT: Walking around the gallery, I think of the physical space some of your sculptural work inhabits, and how it shares the same space as the viewer. It feels charged in a different way than a painting or drawing. What does craft like basket weaving allow you to do or to communicate that couldn’t be achieved through a flat, two-dimensional medium?

SW: What I’m attracted to about basketry is that you can use objects from your reality to create something that’s inspired by your reality. But it transcends, and you create something new that does not exist in your current reality. Originally, it came from my desire to bring in more found objects that relate to my Mexican-American culture. Now it’s evolved and I see something that is related to contact, border, boundaries, and security. How can I build it and extend off of it? So I have a huge interest in building in a way that transcends the domestic basket.

Working in 2D is a challenge for me. With baskets, I enjoy creating something that doesn’t necessarily need to look classically beautiful or balanced. With painting, that part of me comes out and I don’t know how to not make it a pretty picture. How can I control this so that it communicates more than a beautifully harmonious, balanced surface? I don’t think my work on paper does that now, but I’m curious to investigate in the coming years.

That’s why I’ve not shown paintings before — this is my first time. I think that painting and drawing is a unique sphere of creating something that’s complete within its confines of flatness. I like that sculpture shares the space with you, relates to your body in a specific way. You want to imagine how it feels. It’s tangible.

LT: I really love the piece Transport. I read that having to drive past Six Flags everyday to get to your studio may have embossed the image of a roller coaster in your subconscious. But you also relate this piece to the feeling you get when crossing a border, like the U.S.-Mexico border, which you crossed frequently as a child. Can you talk about how pieces like Transport materialize? Do you start with an idea or do you let the material lead you into its shapes?

SW: I’m remembering things from my past and taking things in from my present. Transport was a response to the previous two pieces that I had made that were infinity forms, and I wanted to take it further. I sketched it, and I was satisfied with the form. It was a hybrid between an infinity shape or Venn diagram, and an ampersand. And all of those things relate to identity and ideas of the border. As I continued, I knew I wanted to weave back into some of the areas to create opaque zones to communicate areas that feel secretive. It relates back to this mythology that the border is full of violence and secret violence — people are traveling through tunnels to get here. And I wanted to add a thinner line, so these tunnels I weave with wire come into play. For me they act as little exits or ways to get from one side of the tunnel-like form faster, like signifiers of agency. You can take them if you so wish.

But then I finished making it and I realized I’m driving by a roller coaster every single day [laughs]. So you’re balancing the memory and what you’re trying to create while following your intuition and then you notice these other things creep in. So now I more openly admire roller coasters. I was thinking about it — roller coasters are all based on movement, adrenaline, excitement, and anxiety. I think those are all feelings you can identify with when you’re trying to move from one country to another or one space into another.

Sarita Westrup, “Transport,” 2022, reed, thinset, cement, wood, milk paint, paint, graphite, 19 x 26 x 5 inches.

LT: That leads me to inquire about how you’re making these sculptural forms. You pointed out to me earlier that the big basket in the center of the show, Presence, was made by weaving for six hours off a huge rock that sits outside the art center. Some of the objects over which you form your sculptures are interesting: plastic Easter eggs, water bottles, rocks. What are some of the (seemingly) strangest objects you’ve used to help form your baskets?

SW: Pool noodles! [The artist has several sitting around her studio.] I have a range of sizes. I use them as a gauge, so that while I’m weaving I can stay consistent in my diameter. So that’s a funny one.

In the past, I’ve used actual molcajetes (a mortar and pestle), or tortilla warmers as my molds.

LT: What other materials or skills are you interested in exploring in the future?

SW: I want netting to be a more prominent part of the work in some way. I want to bring that skill back in. I have a very rich natural dye skill base that I’ve kept in the shadows, and I haven’t figured out how to use it in the work. I think it could come into play on the surface of works in the future, to add more color and meaning.

I also want to keep investing in drawing. I actually applied to a workshop at Penland School of Craft so I could study drawing and painting for two weeks. I’m excited!

Form-wise, I’m really inspired by… the Uline catalog. It has a whole segment for security and barricades. I find the forms very interesting. They’re trying to “keep you safe.” They’re thick and bossy. There’s so much authority inside these shapes. I’m interested in exploring these forms later and also want to investigate more work on the floor.

LT: What do you hope people take from your show? Is there a certain experience or response you’re wanting to cultivate for those interacting with your work?

SW: I feel like I understand, as a person who makes art and experiences art, it can be such an aesthetic and textural experience first and foremost. That’s what I want it to be first — I want people to feel a sense of curiosity. To see that there’s a lot of care in the work, and then to look deeper and appreciate the forms, the textures — to have that desire to touch. And if that can lead them to thinking about how this can relate to movement or identity, or even if they’re so curious as to read the exhibition statement, that’s a really great plus for me. If I can get them to that place, it’s about them seeing the beauty of the borderlands and appreciating it as a place of inspiration.

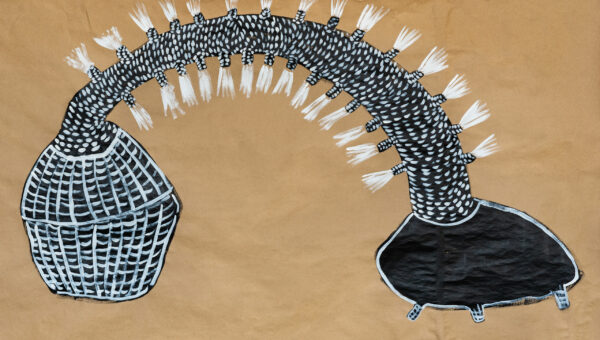

Installation of exhibition featuring “The Non-Linear Route,” 2023, Reed, mortar, metal, twine, hardware, paint, graphite, 48 x 77 x 12 inches.

The Tension of Connection is on view at Arts Fort Worth through April 1, 2023. Learn more about Sarita Westrup and her work during an Artist Talk on April 1 at 1pm at Arts Fort Worth, or learn how to make your own basket at her Twined Basket Workshop on March 25 from 10 am-2 pm.