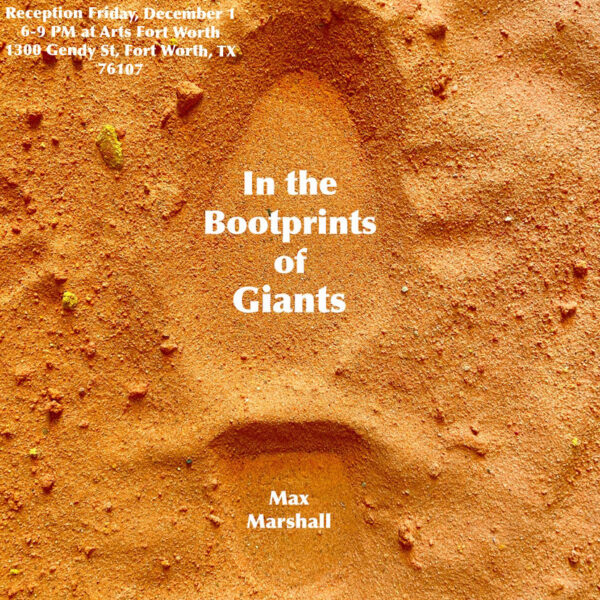

Recently, I had the pleasure of attending a wonderful opening at Arts Fort Worth. Of the many shows on view, I specifically went to see In the Bootprints of Giants by Fort Worth-based artist Max Marshall. Being a somewhat recent transplant to the DFW area, I had come across Marshall’s Instagram around a year ago through some friends and found her work (a mix of western pop and Americana artifacts) playful and enticing.

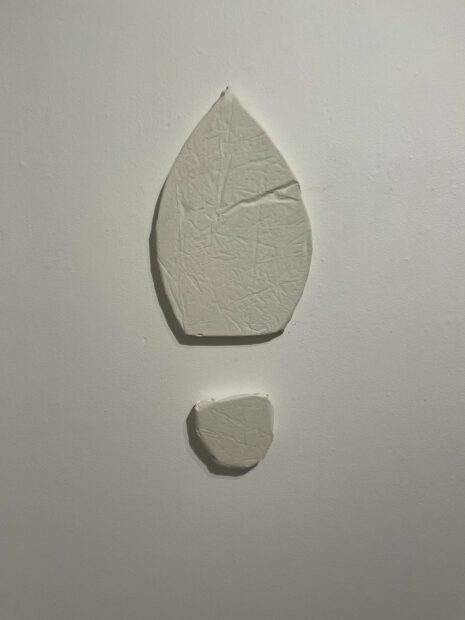

Perhaps due to the limitations of Instagram, I had thought of Marshall mainly as a sculptor, so as I entered the ample gallery space, I believed I was looking at a group of discrete sculptures instead of a sole composition. Standing in the middle of the gallery, you can see objects of unusual sizes, which are somewhat scarcely set near the walls and loosely connected by an encompassing old west theme.

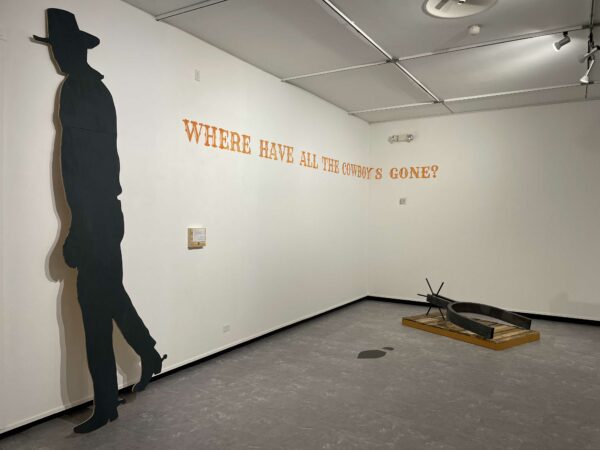

The first object to catch my eye was an enormous yellow hat made of a kind of foam, perched on a rustic wood panel, perhaps belonging to a giant baseball mascot or an inflatable cowboy from a Macy’s parade. On the right side of the room a small installation, or diorama, covers the wall and flows into the floor, depicting a colorful western landscape with cacti and a bull’s skull. On the left side stands an attractive figure, a larger-than-life silhouette of a cowboy that evokes the Marlboro billboards on Sunset Boulevard that you can now only see in the movies. The black, 11-foot-tall cut-out sits next to text painted on the wall in an orange, western typeface that reads: “Where have all the cowboys gone?”

I noticed a label affixed to a wooden box on the wall, which turned out to be a speaker with a voice recording that drawled the following text:

HOW TALL WERE COWBOYS?

In some folklore, the cowboy is said to be the height of two grown men, one standing on the shoulders of the other. Still, other legends suggest the cowboy was as tall as a mountain, blocking light with their wide-brimmed hats, creating both solar and lunar eclipses. Although the largest complete cowboy skeleton ever recovered was 40-feet-tall, experts have hypothesized that juvenile cowboys could have been as short as 11 feet, with some adult cowboys growing as tall as 60 feet.

Commissioned by Marion Morrison [1], this painted plywood silhouette stands at the height of a juvenile cowboy.

After reading the label, of course, it became clear that concept was the main dish, so to speak, and that the objects around the gallery were mostly props used to illustrate the conceptual. The image of a 40-foot cowboy skeleton being unearthed by scientists clearly evokes the idea of a natural history museum devoted to a mighty creature (now extinct?) of the American West. It certainly is a lovely juxtaposition, if anything, because dinosaurs and cowboys are endearing staples of our culture and inextricable parts of our childhoods.

As I looked down at the immense steel spur set on a platform on the floor, it occurred to me that the aim of the show was not that different from what surrealists like René Magritte or Méret Oppenheim had accomplished in some of their works. This is, the merging of two subjects, or registers, that would have never been imagined together, as the means to create an indelible impression, and more importantly, spark novel sensations about the nature of things. In the case of Marshall’s installation, we are not only talking about a combination of objects and scale, but about the combination of concepts themselves: on one hand, the institution of the natural history museum, and on the other, the aura of the American cowboy. The result, at least for me, was to consider the cowboy as a prehistoric giant, a mythical, yet real being, worthy of archeological study [2].

Cultural products or icons, such as saints, superheroes or cowboys, are equivalent to fossils of our civilization [3]. They synthesize a particular set of beliefs that belonged to a specific era and might be the only remnants of the values held by the people who created them. For example, what will humans 10,000 years from now think about Spiderman, Our Lady of Guadalupe, or an Elvis Presley song? (Imagine a team of future Texan Egyptologists conducting careful exhumations of Big Tex’s effigy and trying to interpret the religious banquets and mechanical rituals that took place in his honor every year at the State Fair.)

At the same time, as I walked around and read the other labels in the show, I could not ignore the banner that kept unapologetically asking: where have all the cowboys gone? Being from the generation that I am, I couldn’t help thinking about the 1997 hit song of the same name by Paula Cole. And then I started pondering: could this be a hint by Marshall that she sympathizes with the sentiments expressed in the famous song and perhaps secretly longs for a time long past when men were “real” men? What’s the cowboy if not a myth filled with patriarchal traditions and an idealization of masculinity? But maybe this is an erroneous interpretation, far from what the artist thinks or intended. Who knows? That’s all part of the fun of looking at new art: the joy of healthy speculation.

As you keep walking around contemplating the artworks in the show, you find more of the wooden boxes with labels and the voice-over recordings. Each one of the labels explains both what you are looking at and the origin of each artifact. For instance, one of them tells us about how cowboys might have looked back in prehistoric times (it turns out their wide-brimmed hats were made of a kind of wool crafted from the dried innards of cacti), while another informs us of the cowboy’s natural habitat (for example, how large rocky outcroppings frequently served him as furniture). All these texts are sprinkled with names of patrons who have commissioned or donated some of the artworks. Each of these names represents a real person that actively participated in the creation and perpetuation of contemporary cowboy mythology. For example, the steel spur is documented as being “Gifted by George W. Trendle and Fran Striker.” Fran Striker originally created the character of the Lone Ranger, while George W. Trendle produced the Lone Ranger radio and television programs.

All over the gallery floor there are scattered bootprints, which of course continue and support the analogy of cowboys being prehistoric creatures. I find the analogy endearing, but perhaps not enough to move me beyond intellectual pleasure. The objects are playful and a bit campy, but it is the label text which constitutes the poetic force and the heart of the installation.

As I left the gallery, the deeper nostalgic aspect of the show suddenly hits me. Where indeed have all the cowboys gone? Where does everything go? From the Titans to Gilgamesh and from Hercules to Paul Bunyan, every giant, no matter how grandiose its bootprint, must eventually disappear.

The truth is that armed with insight, sensibility, and a modicum of materials, Max Marshall achieves a revealing new take on an old theme, or at least a charming and elegant one. But don’t take my word for it, come experience In the Bootprints of Giants at Arts Fort Worth; the show is on display until January 20, 2024.

1. Birth name of a certain John Wayne.

2. However, cowboys and dinosaurs have been paired together before, at least once, in the campy 2015 film Cowboys vs Dinosaurs with Eric Rogers.

3. This idea is not mine — I recently heard it in a podcast from professor Gad Saad.