The first day of the 2022 fall semester marked my one-year anniversary as Curator of Art at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum (PPHM) in Canyon, Texas. Throughout the last year many would ask how things were going. Oftentimes, my response was “it’s a bit like drinking from a firehose.” Usually meant to be a joke, this was actually appropriate, considering I stepped into a role at the largest history museum in the state of Texas, and as the successor to an expert in the field with a 30+ year tenure.

The volume of information within the museum, and required to do my job, is immense. The learning curve is steep, and deadlines are prolific and immediate. I have been hard at work to meet all the demands, but I have ended up with water up my nose on more than one occasion. Recently, while discussing the job with a colleague, he suggested that I look for a handful of things within the museum that inspire me, then examine them more fully in order to better understand both my position and the collection. Asking me to choose my favorite artist or artwork is like asking which of my children I love best. However, using Glasstire’s own Top Five as my inspiration, that is exactly what I tried to do, with full knowledge this list will continually change and evolve.

Years ago, before I was on staff, I visited PPHM with several of my cousins from the Midwest. We were trying to fill a summer afternoon and someone suggested we go to the museum, knowing it would be an air-conditioned respite from the heat. I hadn’t been in the building in years and I remember I wasn’t particularly interested in visiting because I thought it would be dull and predictable. To my surprise, I was immediately struck by the beauty of the space.

The relatively small Windmill Gallery is off an enormous two-story room walled in glass, which emphasizes a low ceiling and angled walls. The room is filled with enormous windmills installed low to the ground, amplifying their size. As they’re usually seen from a distance, the close proximity of the windmills forces us to encounter them from an entirely new perspective, close-up and at eye level. The huge installations reach from floor to ceiling, swallowing the space, and are beautifully graphic in an abstract way, echoing modern art. They no longer read as functional windmills, their blades turning to pump life-giving water to the early pioneers of the region, but as lines radiating from a central point that dwarf everything else in the room and transcend their expected, iconic westernness.

I discovered this nude in the art storage vault shortly after I came on staff, and immediately fell in love with it. Something in the work speaks to me; the dark moodiness of the greens and blues in the background, the way the figure languidly gazes out at the viewer, the light falling from the right side of the image, and her hands loose and relaxed as they drape over the pillows on which she reclines all make for a scene both familiar and exotic.

Naturally, I did some research on the painting and discovered that the Hungarian-born artist, Geza Kende (1889-1952), was a well-known landscape and portrait painter who spent most of his life in Los Angeles. His commissions included those of famous actors of the time such as Lucile Ball, Clara Bow, and fellow Hungarian Bela Lugosi. The artist’s history makes this piece an unexpected addition to the museum’s traditionally western collection.

By its very nature, a collection of early Texas and southwestern art is somewhat predictable, but this painting’s association with the stylized aesthetic of post-war Los Angeles gives the work an air of celebrity, connecting it to a larger world. While the Panhandle is well known for being remote and out of the way, I regularly find connections, in both the museum and the larger community, that reach outside of our defined ideas of westerness and engage in broader conversations. This painting is emblematic of a thread that repeats itself often in the collection: a recontextualizing of artworks as outliers of the expected.

Among the many things I inherited when I moved into my office were three cabinets full of artist files. I realized early on that these were essential to understanding the museum’s collection, and I created a plan for reading them all and also devising a finding aid as I went along. Working in alphabetical order, it wasn’t long before I opened Lloyd Albright’s (1886-1950) file and discovered he was an artist from Dalhart, Texas who spent time each year in Taos, New Mexico with artists such as Emil Bisttram and W.H. Dunton.

Dalhart is a small community in the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle and, coincidentally, it is also my hometown. As I read through Albright’s file, I came across newspaper clippings and correspondences with names that I remembered from my childhood, including people I hadn’t thought of in years. There were also stories referenced that I vaguely remembered, but was too young to pay much attention to or to fully understand. My mother is also an artist, and eventually I came across her name in a clipping and sent her a text, which then led to a conversation in which she revealed things about herself I had never known.

It was such a comforting feeling to be surrounded by familiarity while sitting, overwhelmed, in a strange new office. I am extraordinarily proud of where I am from, and I had no idea how personal this job would be for me. Being responsible for this collection has provided opportunities to learn more about myself and the art of this region, and has also helped me realize that I have been closely connected to these places and artworks for most of my life. When I see this painting, I remember that moment in my office, reading a file about people long gone, through an artist far removed from a place I hold so very dear.

I am the daughter of a farmer, and the product of generations of farmers. I was born in Indiana and moved to the Texas Panhandle in 1981, and have spent my entire life surrounded by agriculture. As a kid, I rode along with my dad as he checked irrigation wells. I drove a tractor during the summers, and often came home from college to work harvest. Early Washburn by Ignatz Sahula-Dycke (1900-1982) represents everything romantic and familiar about this part of my life. Through the piece I can reminisce about the light that filters through the fine dust of a wheat harvest as the sun — which hangs heavy in the air — begins to set, adding a shimmer to the golden light of the long Texas days.

The canvas takes up an entire wall at the end of the PPHM’s gallery, and is almost like a window into the huge skies and wide horizons the Panhandle is known for. It invites viewers to step inside the frame, to nod at the passing cowboy and walk down the street alongside the farm trucks. I can hear the hum of machinery and the sounds of the grain elevator. I smell the sweet, heavy fragrance of grain as the day begins to get long and the air begins to cool.

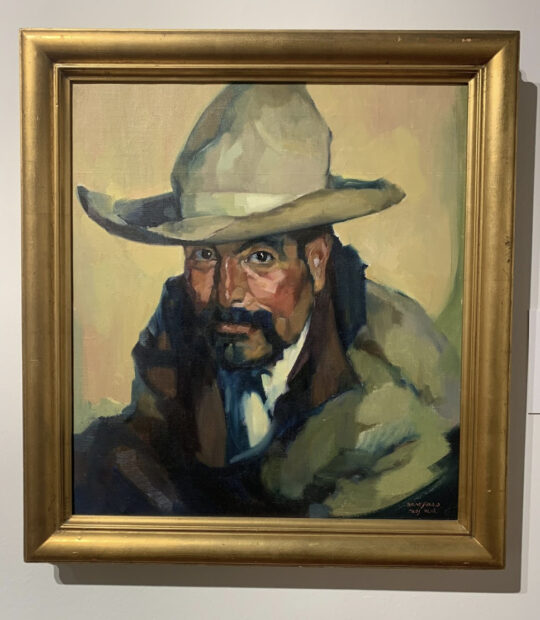

I have always loved a good portrait. My camera roll is full of them, and I am especially enraptured by John Singer Sargent’s portraits. What draws me to most portrait works is the expression on the sitter’s face. This is certainly true for Westerner, a painting of an anonymous man in the PPHM’s Southwestern Art Gallery. The figure is dressed in a work coat and hat; he has dark hair and a mustache, and his expression is ambiguously playful and engaging.

It is not only the expression that I’m drawn to — I have also fallen in love with the color palette artist Hans Paap (1890-1967) uses in the piece. The wind-chapped cheeks of the figure are rosy, the acidic green of his jacket contrasts with the deep brown of his lapel, and all are set against the warm yellows and pinks of the background. Much like Sargent’s, Paap’s brushstrokes are quick and loose; a small dab of paint creates the twinkle in the figure’s eye, and a hasty white line highlights the bridge of his weathered cheek.

In some ways I often think I share the same sentiment as the Westerner, weather beaten after my first, very long year into this new role. It has been overwhelming, but tremendously rewarding. I’ve learned so much about the museum, about the place I call home, and about myself. Taking the time to recount a handful of those small moments has helped me refocus my energy anew for a second year and, hopefully, many more to come.

Deana Craighead is the Curator of Art at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas. She joined the museum in August 2021.

4 comments

Love this commentary. Makes me want to take a road trip

Great read! I enjoyed experiencing PPHM through your eyes and personal connections. Thank you for sharing!

What about all those magnificent Frank Reaughs? Not 1 in your top5?

You are absolutely correct that the work of Frank Reaugh is magnificent and he would certainly make a top 5 list of the most significant objects in our collection. For this project however, I wanted to write about the ways in which I personally connected with the collection as I found my way in a new museum.