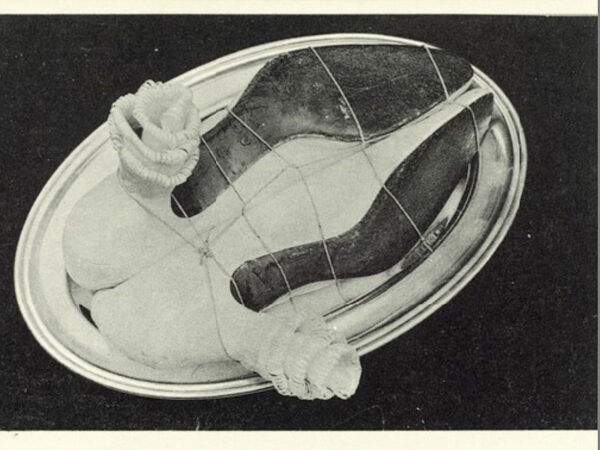

Person with Meret Oppenheim’s “Object” (1936), detail, photograph, 1936. Photograph: AP/John Lindsay.

Meret Oppenheim (1913-1985) created two of the most astonishing Surrealist objects (the fur-covered tea service and the bound high-heels on a platter), and I have always hoped to see a full retrospective of her work. Many of her key pieces are sequestered in private collections, and only one museum has a large collection of her art. Consequently, I was elated to experience her five-decade long career courtesy of the transnational retrospective, Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition at the Menil Collection in Houston.

Co-organized by Nina Zimmer, director of the Kunstmuseum Bern (the chief repository of Oppenheim’s work), associate curator Natalie Dupêcher at the Menil Collection, and Anne Umland, senior curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the exhibition, which premiered in Bern, is at MoMA from October 30 through March 4.

The exhibition’s title was inspired by My Exhibition, Oppenheim’s imaginary retrospective, comprised of twelve large drawings (24 x 28 inches) she made in 1983, in which 206 of her works are hand colored and drawn to scale. The Menil exhibited 112 of Oppenheim’s works, 56 of which were in Oppenheim’s twelve drawings.

Oppenheim was an extremely eclectic and wide-ranging artist, and I discuss many high points of the exhibition below, after an introduction to her life and work.

Biography and Overview of Career

Oppenheim was born in Berlin in 1913 to a Jewish German psychiatrist father and a Swiss mother. Her father knew Carl Gustav Jung and had attended his seminars. The artist recorded her dreams in notebooks, beginning at the age of 14, and they often served as source material for her artworks. She was herself analyzed by Jung.

Oppenheim lived with her grandparents in Switzerland during World War I. She studied art at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel in 1929-1930, before moving to Paris in 1932 to become an artist. Oppenheim’s maternal grandmother, Lisa Wenger-Ruutz, was a publisher and writer of children’s books. Oppenheim quit high school to become an artist. She very fortunately chose Paris over Munich because she had a Swiss artist friend (Irene Zurkinden, a Neo-Impressionist painter) who was familiar with the city. Zurkinden made introductions for her. Prior to her move to Paris, Oppenheim had never heard of Surrealism, though she had collected images of several modern art movements.

In Paris, Oppenheim studied for a time at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in 1932, though she preferred museums and café society to classes. Oppenheim came into contact with several Surrealists in 1933, after meeting Alberto Giacometti, whose work impressed her deeply. Giacometti and Hans Arp visited her studio and invited her to exhibit at the 1933 Salon des Surindépendants, a jury-less exhibition that included many Surrealists that year.

Oppenheim exhibited three works (no longer extant) in this show, which were probably paintings with objects added to them. Oppenheim noted in her interview with Roger J. Belton that she had a “Surreal or Surrealistic” nature, and that she was doing Surrealism before the letter (“Androgyny: Interview with Meret Oppenheim,” in Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, and Gwen Raaberg, eds., Surrealism and Women, MIT Press, 1991). (Most of the interview is accessible here.)

At the Salon’s opening, André Breton, who had written the movement’s first manifesto in 1924, invited Oppenheim to attend the nearly daily meetings of the Surrealists at the Café Place Blanche. Oppenheim also modeled for Man Ray and began a sexual relationship with him. In almost no time at all, she had gained entrée into the inner circle of the most important avant-garde movement of that exciting and tumultuous era.

Man Ray, “Erotique voilée” (Veiled Erotic), 1933, photograph (Meret Oppenheim with the press belonging to Louis Marcoussis), vintage print. Photo: Sotheby’s.

In Erotique voilée, the most famous of a series of photographs that Man Ray took of her, Oppenheim holds her palm against her forehead. This dramatic gesture is ambiguous: it could be read as exhaustion or relief. Her smile belies the performative nature of these modeling sessions, in which she enacted a number of scenarios.

Her left hand, shoulder, and forearm bear ink, potentially suggesting that her bare white body is akin to paper, the passive “ground” for the printing of an image. That scenario is explicit in another Ray photograph likely taken shortly before Erotique voilée, in which Oppenheim’s inked hand and forearm are placed over a sheet of paper.

The press’s phallic handle, since it is situated at Oppenheim’s groin, endows her with an iron phallus, which boldly contradicts a reading of her body as a passive agent. Her body collapses into the wheel, seemingly making her a part of the apparatus.

Oppenheim’s eyes are downcast, her haircut is androgynous, and significant portions of her body are obscured by the wheel and its shadows. It is a masquerade in which her mask consists of ink, shadow, and a bit of iron(y). This ambiguous image nonetheless carries an uncanny erotic charge.

In 1934, Breton printed this photograph (cropping out the lower section) in the fifth issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaur. It served to illustrate “érotique-voilée,” the first category in Breton’s short story entitled La beauté sera convulsive (“Beauty will be Convulsive”). That is how Ray’s photograph obtained its title. The most famous line in Breton’s story asserted: “La beauté convulsive sera érotique-voilée, explosante-fixe, magique-circonstancielle ou ne sera pas” (Convulsive beauty will be erotic-veiled, explosive-static, magic-circumstantial, or will not be at all). Ray had previously made a number of photographs of women wearing semi-transparent veil-like fabrics, or bearing cast shadows on their bodies. Here he uses shadows and iron to achieve a similar effect of veiling.

Oppenheim is sometimes credited as a co-creator of Erotique voilée and the other related photographs taken by Man Ray. But she made some very specific disavowals of co-authorship, noting, for instance that she had little knowledge of French at that time. When Belton asked Oppenheim what she thought of the photograph, she replied: “I don’t know. That was Man Ray’s work.” When Belton queried whether it was her work “in any way,” she responded: “Not at all. He was the boss.”

Oppenheim, of course, did come to the project with an androgynous hairstyle that was fashionably modern, and with an interest in androgyny. In 1936 Ed Schmid took a head shot of her in which a man’s suit, shirt, and tie are visible. Oppenheim maintained an interest in the androgyny exhibited in Erotique voilée, which is reflected in some of her artworks. In several instances (discussed below), her works are engaged in dialogues with works by Man Ray.

Garden party at the Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp residence. Oppenheim is in white at top left; Marie-Berthe Aurenche and Max Ernst (who were married) are to her right; Jean Arp is in the center foreground; James Joyce is in the left corner. Photograph: “Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition” website, Kunstmuseum, Bern.

Oppenheim began a yearlong sexual relationship with Max Ernst in the Fall of 1933, which she spontaneously terminated because she realized (unconsciously rather than consciously) that the affair would inhibit her artistic creativity. Having burst onto the Paris scene as a model catapulted to fame by Breton, Oppenheim quickly achieved even greater notoriety as a sculptor, primarily on the basis of a single object. Oppenheim was conflicted by this success. She regarded herself as a painter. As she told Belton: “I have become known as a maker of Surrealist objects, but they were the least of my endeavors. I thought of myself as a picture-maker.”

Oppenheim was a signatory to several Surrealist declarations penned by Breton. In June of 1934, her Head of a Drowned Man was reproduced in a special Surrealism issue of Documents. She was included in the exhibition Cubism = Surrealism in Copenhagen in 1935.

Oppenheim’s position in the Surrealist group was both privileged and subordinate. As Whitney Chadwick puts it:

Oppenheim quickly became known as the perfect embodiment of the femme – enfant, who through her youth, naivety and charm was believed to have more direct and spontaneous access to the realms of the dream and the unconscious. She was celebrated by the Surrealists as the “fairy woman whom all men desire” (“Meret Oppenheim,” Grove Dictionary of Art, online 2003).

Carolyn Lanchner is one of several writers who concurs:

Without the least complicity on Oppenheim’s part, she personified male Surrealism’s ideal of the “femme-enfant,” the uninhibited woman-child who could clear a path to the mind’s creative unconscious while simultaneously arousing sexual desire (Oppenheim Object, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2017).

In her interview with Belton, Oppenheim specifically denied that she was a femme – enfant (the phrase had been coined by Breton).

Oppenheim made extraordinary works (treated below) in 1936 that enabled her to break several glass ceilings and that brought her great acclaim. She garnered a solo exhibition at the Galerie Marguerite Schulthess (April 18-May 8) in Basel, where she was spending much of her time in 1936. Dupêcher identifies a number of works in the Schulthess exhibition in her essay in the exhibition catalog, which is titled “‘FINALLY FREEDOM!’ The Work of Meret Oppenheim, 1932-1954.” In 1936, Oppenheim was also featured in high profile Surrealist exhibitions in Paris (in May), in London (in June), and in New York (in December). Oppenheim’s potential and the opportunities afforded to her through her Paris contacts seemed to be unlimited. But this world of art suddenly came crashing down.

The rise of the Nazis threatened Oppenheim and her parents. The latter had resettled in an ancestral paternal home in rural Germany. For a short history of anti-Jewish laws in Germany, see “Anti-Semitic Legislation, 1933-1939,” Holocaust Encyclopedia. Oppenheim’s mother returned to Switzerland in 1935. Her father, who was a country doctor, lost his ability to practice his profession in Germany. He, too, moved to Basel in 1936, where he was unable to work.

Oppenheim was thus deprived of her economic support. Her permanent move to Basel in 1937 brought to a close the most exciting and artistically significant phase of her career. We can only imagine what Oppenheim might have achieved if her momentum in the artistic hothouse of pre-war Paris had not been so brutally interrupted. The outbreak of World War II closed one of the most exciting chapters in the history of the avant-garde. The Paris Oppenheim had known for a few precious years in the 1930s would be gone forever.

Oppenheim fell into a depression and creative malaise (during which she destroyed many of her works) that lasted until 1954, though she created several important extant artworks in that interim period. She studied painting, restoration, and anatomy at the Allgemeine Kunstgewerbeschule, a vocational trade school in Basel. Her ability to paint representationally improved substantially. The training in restoration was also useful when Oppenheim subsequently fabricated sculptures that included frames and other appropriated objects. She also became a member of Gruppe 33, a Swiss antifascist art collective. It utilized masks (some of which Oppenheim made) in politicized processions during Carnival. Oppenheim also joined the Künstlervereinigung Allianz, an association of Swiss artists founded in 1937. As Oppenheim told Belton, “I recovered my pleasure in making pictures very suddenly in late 1954. I just walked out the door and rented a studio” in Bern. Her artistic career was reinvigorated. She ultimately moved to Bern and remained there for the rest of her life.

Oppenheim designed masks, costumes, and sets for Picasso’s play Le Désir attrapé par la queue (Desire Caught by the Tail) in 1956. Her performance piece Frühlingsfest (Spring Feast, 1959), made for three couples, consisted of a banquet served on a nude woman that was meant to celebrate the earth’s fertility and springtime bounty. Breton urged her to restage it for his Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS), held at the Cordier Gallery in Paris (1959–60). Breton called it Cannibal Feast. It was presented in a voyeuristic manner (click here for a short video). The altered title and mode of presentation served to transform the meaning of Oppenheim’s performance. As Oppenheim told Belton: “the original intention was misunderstood. Instead of a simple spring festival, it was yet another woman taken as a source of male pleasure.” The Paris iteration was criticized for objectifying women. Thereafter Oppenheim never participated in another Surrealist exhibition. Breton died in 1966.

Meret Oppenheim, Radiograph of skull of M.O.,1964, collection of Dominique and Christoph Bürgi, Bern. Photograph: MoMA.

Oppenheim was given a retrospective at the Modern Museum in Stockholm in 1967. Though she wanted to use the x-ray image illustrated above in the exhibition catalog, Man Ray’s Erotique voilée was utilized instead. Oppenheim received the Basel Art Prize in 1975, and she was awarded the Grand Art Prize from Berlin in 1982.

Oppenheim did not utilize a single, recognizable style, nor did she — in any phase of her career — exhibit any kind of conventional artistic development. Moreover, just as she favored experimentation, she — in her later years — resisted categorization, either as a Surrealist or as a woman artist. This is why Oppenheim ultimately declined invitations to participate in Surrealist and women-only exhibitions.

Margrit Baumann’s photograph of Meret Oppenheim, 1982, with her sculpture “Six Clouds on a Bridge” (1975) at the Kunstmuseum, Bern. Photograph: Kunstmuseum, Bern.

Perhaps Oppenheim’s most famous quote is from the speech she gave upon receiving the 1975 Basel Art Prize:

If someone is speaking his own new language, which no one else understands yet, then sometimes he has to wait for a long time to hear an echo. It is even more difficult for a female artist … Artists are expected to lead the kind of life that suits them — and his fellow citizens turn a blind eye to that. But if a woman does the same thing, then the eye pops open. One has to accept this and many other things. Yes, I’d even go so far as to say that, as a woman, one is obliged to prove via one’s lifestyle that one no longer regards as valid the taboos that have been used to keep women in a state of subjugation for thousands of years. Freedom is not given; one has to take it.

Meret Oppenheim awarded the Basel Art Prize at the University of Basel, January 16, 1975. Photograph: Kunstmuseum, Bern.

In her interview with Belton, Oppenheim reiterated her views on androgyny that were influenced by Jungian rather than Freudian psychology:

… any great artist expresses the whole being. In a man, a feminine part helps in the creation of this expression. In a woman, there is a corresponding masculine component. … Jung placed more emphasis on the collective unconscious and on archetypal images. … But my father didn’t understand what Jung had to say about the feminine part of a man. None of the men understood women.

Oppenheim’s Works from the Early 1930s

Oppenheim had made drawings since she was a child, though she did not have a great deal of formal training in art. Several of her early works have a playfully macabre character that would have appealed to the Surrealists.

Meret Oppenheim, “Votive Picture” (Strangling Angel) (Votivbild [Würgengel]), 1931, India ink and watercolor on paper, 13 3/8 × 6 7/8 in. (34 × 17.5 cm), Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, long-term loan from private collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Meret Oppenheim, “Votive Picture” (Strangling Angel) (detail) 1931. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

But this angel also has very sinister qualities. She has slit the throat of a naked infant — presumably with her bloody fingers. The child’s arms are outstretched as it bleeds profusely onto the angel’s skirt and the ground below. The ground, meanwhile, is littered with the corpses of women the angel has slain. They are represented by legs terminating in heels that stick out of the ground like bizarre plants.

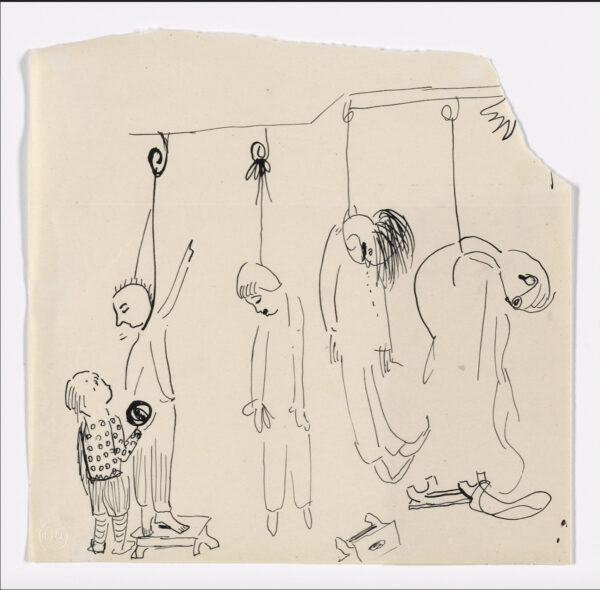

Meret Oppenheim, “Suicides’ Institute” (Selbstmörder-Institut) , 1931, also dated 1932, India ink on paper, 7 1/2 × 7 11/16 in. (19.1 × 19.5 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor and Committee on Drawings and Prints Fund. Photograph: Museum of Modern Art.

In the Suicide’s Institute, a man who is about to be hung offers instruction to a boy with a ball who is presumably to assist in his hanging.

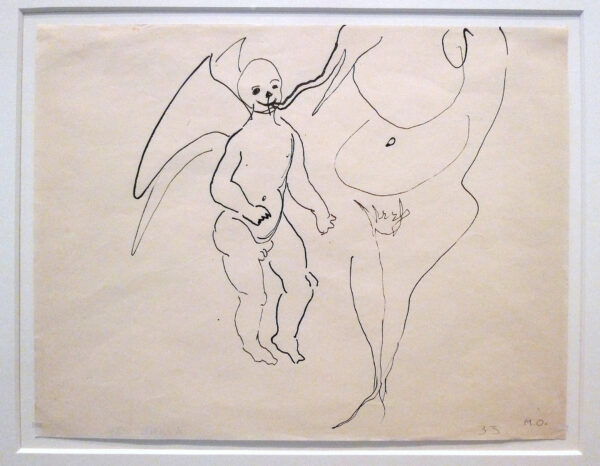

Meret Oppenheim, “A Boy with Wings Sucks on the Udder-Shaped Breast of a Woman” (Ein Knabe mit Flügeln saugt an der euterförmigen Brust einer Frau), 1933, india ink on paper, 8 1/4 × 10 5/8 in. (21 × 27 cm), Kunstmuseum Bern. Meret Oppenheim Bequest. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Works like A Boy with Wings, made with casual facility, presage Louise Bourgeois’ graphic works.

Meret Oppenheim, “Quick, Quick, the Most Beautiful Vowel is Voiding (Husch-husch, der schönste Vokal entleert sich)”, on recto M.E. par M.O./M.E. by M.O., 1934, oil on canvas, 17 15/16 x 25 5/8 in. (45.5 x 65 cm), Bürgi Collection, Bern.

Oppenheim depicts a ball and chain attached to a bar, above which six forms float freely. The ball, rather than a heavy solid, is an evanescent collection of painterly brushstrokes that seems to be in the process of disintegration. The inscription indicates that it is a portrait of Max Ernst by Meret Oppenheim.

Meret Oppenheim, “Little Ghost Eating Bread” (Kleines Gespenst, Brot Essend), 1934, oil on canvas, 20 × 17 in. (50.8 × 43.2 cm), private collection.

Here Oppenheim takes a biomorphic figure familiar from the work of Joan Miró and situates it within a comic narrative.

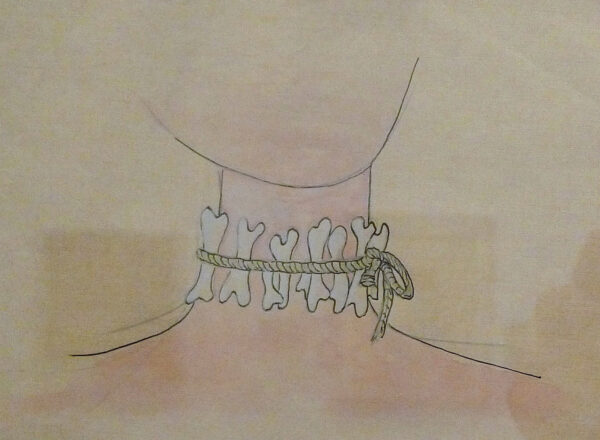

Meret Oppenheim, “Necklace” (Halsband) (cropped), 1934-1936, ink, gouache, and watercolor on paper, 7 1/2 × 7 7/8 in. (19.1 × 20 cm), Design Museum Den Bosch‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

This drawing imagines a necklace made of small bones fastened to a woman’s neck by a rope. It is about as elemental and primitivizing as the bone-in-the-hair worn by the cartoon character Pebbles Flintstone. Oppenheim ultimately developed it into a brass necklace of bones held by a double chain, with a mouth in the center.

Meret Oppenheim in 1936

1936 was Oppenheim’s annus mirabilis. If her artistic career had ended in 1937, she would still be regarded as an important artist because of the work she completed in 1936.

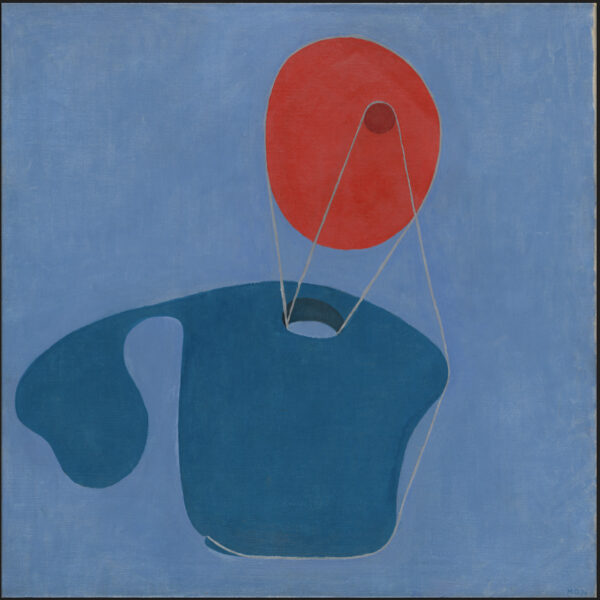

Meret Oppenheim, “Red Head, Blue Body” (Roter Kopf, blauer Körper), 1936, oil on canvas, 31 5/8 × 31 5/8 in. (80.3 × 80.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Meret Oppenheim Bequest.

Red Head, Blue Body is the only work that Oppenheim bequested to MoMA, so she must have regarded it as a very important painting, and one that fit in well with the museum’s collection of biomorphic art by artists such as Jean Arp, Joan Miró, etc.

The head and body are so abstracted in Red Head, Blue Body that, without the title, we would not be certain that she was referencing a body. The red head is floating into space, like a helium balloon, which is why it is tethered to the blue body with a gray cord (primarily through the neck hole).

At this point in her career, Oppenheim was not very experienced with oil paint. Moreover, this piece is rather large and ambitious compared to her earlier paintings. Judging from the pentimenti, it took Oppenheim considerable time to paint it. Given the factors noted above, it is likely that Red Head, Blue Body was painted well in advance of the Schulthess Gallery opening on April 18. Both Red Head, Blue Body and the assemblage discussed directly below feature binding with string.

A Georges Hugnet postcard using Dora Maar’s photograph of Meret Oppenheim’s “Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen.” Verso, upper left, imprinted in black ink: “LA CARTE SURREALISTE/ GARANTIE” [in a circle, in the style of a postage cancellation mark]; upper center, imprinted in black ink: “POST CARD”; center, imprinted in black ink: “PRINTED IN FRANCE” [printed vertically]; lower left, imprinted in black ink: “Premiere Serie No 14/ MERET OPPENHEIM:/ / /,” Getty Museum. Photograph: Getty Museum. This postcard records the original version of Oppenheim’s work, before it was destroyed under circumstances described below. I think the heels look thicker than those in the extant version, which was made in 1967 for Oppenheim’s retrospective in Stockholm.

Oppenheim’s assemblage was first shown at the Schulthess exhibition that opened in April in Basel. In this context, Dupêcher refers to it in her catalog essay as “the brand new work then known as “Shoes: Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen.” Thereafter Oppenheim dropped the “shoes” from her trilingual title.

Meret Oppenheim, “Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen,” 1936/1967, metal plate, shoes, string, and paper, 5 1/2 × 13 × 8 1/4 in. (14 × 33 × 21 cm), Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Photograph: Moderna Museet.

Anne Umland, co-curator of Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, told the Wall Street Journal (October 15, 2021) that Oppenheim’s construction evokes “images of women, images of domesticity, images of bondage and restraint, limits on freedom — all in this object that makes you laugh out loud.”

Subjugation, sadism, eroticism, labor, and cookery are preposterously — but inextricably — bound, lashed together on a silver platter and served up for all to see. Potential interpretations abound.

The title is mysterious and hard to fathom. In a June 8, 1982 letter to Jean-Christophe Ammann, Oppenheim provided crucial insights into her title and into the work’s symbolism. She said it evoked: “… the association of thighs squeezed together in pleasure. In fact, almost a ‘proposition.’” This statement confirms that Oppenheim associates the shoes with sexual pleasure. One wouldn’t have to be a Freudian to say that in this context, they are fetishistic substitutes for female thighs, evoked by the tan bottoms of the shoes.

In the letter to Ammann, Oppenheim adds:

When I was a little girl, four or five, we had a young nursemaid. She was dressed in white (Sunday Best?). Maybe she was in love, maybe that’s why she exuded a sensual atmosphere of which I was unconsciously aware.

The key to the title is the sensual aura radiated by the nursemaid who was employed in the Oppenheim home when the artist was a child. The artist’s age at that time and the assemblage’s trilingual title make it clear that the servant in question was a nanny rather than a wet nurse.

Someone employed to look after a young child would not — of course — wear such impractical shoes. But practical shoes, like the kind worn by actual nannies, would not have the desired effect of radiating sensuality. Heels symbolize eroticized motion, not the motions necessary to attend to another person’s child in another person’s domicile.

Renée Riese Hubert notes that the heels facilitate another association: Oppenheim “problematizes the feminine without referring directly to a body and even less to a face.” As prototypically “feminine apparel,” the heels “expose their full curvature.” The curves of the shoes are thus analogized to the curves of the female body. Through the act of binding the shoes, women are likewise analogized to game fowl. Hubert draws a further conclusion: “The frills and the strings contribute both to cannibalization and feminization” (“From Déjeuner en fourrure to Caroline: Meret Oppenhiem’s Chronicle of Surrealism,” in Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, and Gwen Raaberg, eds., Surrealism and Women, MIT Press, 1991). (Most of the chapter is accessible here.)

Hubert turns next to the paradox of the pair: they are bound into a “mutual and common imprisonment.” Thus, “hypothetical movement is transmuted into a single immobile package.”

Hubert also discusses another important Oppenheim assemblage from 1956 called the The Pair, which consists of an old pair of women’s high-top shoes, which are unlaced and fused at the toe (a version of this object from 1967 is in the MoMA iteration of the exhibition).

The pairs of shoes in both works have certainly traveled on human feet. They were agents of locomotion that have been arrested for the pleasure of visual consumption.

High heels, even in everyday use, impede “normal” locomotion, which is why they are sometimes compared to traditional Chinese foot-binding. At the same time that they inhibit motion, the heels function as miniature columns that “display” the wearer of these shoes. Thus, one can say that, by tying the high heels up on a platter, Oppenheim took some inherent and distinctive characteristics of high heels to their ultimate conclusion.

Oppenheim, in fact, told Belton of her imaginary scenario in which women rejected men, and men could only catch slow women. These slow women were then “effectively ‘bred’ by men so they would be subordinate. So that men could wield power….” This seems to add another potential layer of meaning to Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen.

Is it a sufficient basis to speculate that Aurenche (symbolized by her bound and captured heels) might have been associated by Oppenheim with a slow woman that Ernst caught (married), whereas Oppenheim herself eluded him?

Janine Catalano argues that Oppenheim’s work “takes its place in a complex social and art historical tradition surrounding the objectification and availability of women’s bodies” (“Distasteful: An Investigation of Food’s Subversive Function in René Magritte’s ‘The Portrait’ and Meret Oppenheim’s ‘Ma Gouvernante—My Nurse—Mein Kindermädchen,’” Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Studies, Issue 14, Winter 2010.)

The heels Oppenheim selected for her assemblage are dirty and worn. As Catalano observes: “Scuffed and worn, they reveal a tarnished, dirty underbelly that is generally hidden, but whose visibility here is highly significant.” She notes Freud’s observation in Civilization and its Discontents (1930) that “dirtiness of any kind seems to us incompatible with civilization.” She also points out that sin is frequently equated with stain in Christian symbolism.

Catalano concludes that Max Ernst, the dissident Surrealist writer Georges Bataille, and Oppenheim:

… have turned this concept on its head by citing enforced chastity and the rejection of natural corporeal lust and love as the true danger to humanity. Dirt thus becomes a powerful declaration, an embrace of sexuality and a defiance of its classification as taboo. If cleanliness is next to godliness, the surrealists preferred to worship in the church of mud puddles.

We should also note that no shoe fetishist wants unworn shoes. Freud, in fact, noted a link between smell and foot/shoe fetishism.

Meret Oppenheim, “Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen,” 1936/1967, metal plate, shoes, string, and paper, 5 1/2 × 13 × 8 1/4 in. (14 × 33 × 21 cm), Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova. From the rear, the frilled heels really do look like chicken drumsticks.

As Dupêcher stated in an email to the author:

Ma gouvernante—My Nurse—Mein Kindermädchen is one of Oppenheim’s most salient artworks. Oppenheim brings together her skill at transforming found objects, her fascination with codes of femininity, her ear for linguistic play, and her signature macabre sense of humor. Oppenheim herself held this work in high regard. This is revealed by the fact that she remade it in 1967, in conjunction with her first lifetime retrospective at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

Lisa Wenger, who is Oppenheim’s niece, provides some information about Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen in her conversation with Dupêcher at the Menil Collection. Wenger explains how the first version of the assemblage was destroyed. After the work had been delivered to the Ernst household via post, Marie-Berthe Aurenche removed the shoes (which, as noted above, had been hers to begin with) and “gave the shoes to a poor woman and that was it.” So the most crucial part of the artwork evidently walked away as an act of charity. By this account, the work was not destroyed — as is often alleged — by an angry female visitor at an exhibition. Aurenche herself freed the pumps from their artistic/fetishistic bondage and restored them to their proper function. Oppenheim’s multiple accounts of the work’s creation and destruction make it difficult to be certain about its basic history.

Somehow, despite Barr’s request, Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen never made it to the MoMA exhibition where Oppenheim’s fur-covered tea service became such a sensation that it is still regarded as the supreme Surrealist object. Nonetheless, it appears to have been included in the International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galeria de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City in 1940. Therefore, Dupêcher suspects that “it was probably destroyed sometime after, in the early 1940s.”

Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen would not be reborn until Oppenheim recreated it for her 1967 Stockholm retrospective — or perhaps it would be more famous than it is today.

Additionally, Wenger provides insight into a women-only exhibition to which Oppenheim uncharacteristically consented to participate, though she had said she would never do so again. It was Lea Vergine’s 1980 “landmark exhibition” in Milan called The Other Half of the Avant-Garde (Wenger mistakenly refers to it as The Other Half of Surrealism). When Wenger and Oppenheim came across Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen at the Milan opening, the two shoes had been untied and placed soles down on the platter. The art handlers must have thought that the string was part of the transportation packaging. Oppenheim had to scramble to find string, truss the shoes properly, and invert them on the platter.

To return to the Man Ray-Oppenheim dialogue, Ray’s Enigma of Isidore Ducasse of 1920 (a sewing machine wrapped in a blanket and bound by ropes) provided a precedent for the ropes utilized in Red Head, Blue Body and Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen.

Additionally, Ray’s Venus Restored, which was originally made in 1936, appears to be in dialogue with Oppenheim’s contemporary bondage-themed assemblage. Ray took a cast of a headless and limbless Medici Venus, which he then bound with rope in an elaborate, bondage-fetish manner.

But this is a senseless bondage, since there are no limbs to restrain. Moreover, the cast’s “flesh” doesn’t yield to the ropes like real flesh. Instead, its skin is as impervious as stone or armor. It is akin to trussing a hard plastic chicken with no head, legs, or wings — or, for that matter, a pair of women’s heels. In this work, Ray ironizes bondage. He utilizes a fragmented classical ideal of beauty, but, despite his title, he fails to restore any of its missing parts. Nor do his fetishistic ropes have any noticeable effect on his impervious object, which lacks even a head to survey or react to them.

Meret Oppenheim, Fur bracelet, 1936, brass bracelet covered by ocelot fur. Photo: Maison Schiaparelli.

Oppenheim designed jewelry for Elsa Schiaparelli to supplement her income after her family’s finances were imperiled by the Nazis. She was wearing an example of the above bracelet when she encountered Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at the Café de Flore in Paris. According to one version of the story recounted by Oppenheim, Picasso quipped that anything could be covered with fur. Oppenheim replied: “Even this cup and saucer.” This café council must have taken place after January 7 (when Picasso and Maar met) and before March 25, when Picasso left Paris on a long trip (dates specified by Dupêcher’s research).

After she was invited by Breton to participate in the first exhibition of Surrealist objects at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris, Oppenheim subsequently purchased a cheap cup, saucer, and spoon at a department store. She proceeded to cover the objects with fur that she had on hand, allegedly from a Chinese gazelle. (Though Oppenheim described it as such, MoMA determined years ago that it is not Chinese gazelle, though they could not determine precisely what kind of fur it is.) Oppenheim must have completed this task before mid-April, when she departed for her exhibition in Basel (Man Ray photographed the completed work, which was published in Cahiers d’art in May). In short order, Oppenheim’s hairy tea service became the quintessential Surrealist object.

Meret Oppenheim, “Object,” 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4 3/8″ (10.9 cm) in diameter; saucer 9 3/8″ (23.7 cm) in diameter; spoon 8″ (20.2 cm) long, overall height 2 7/8″ (7.3 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

It is jarring to see smooth and sanitary utensils transformed into hairy objects. One can only imagine wanting a sip of tea and getting a mouthful of shaggy bristles instead. Object is only seen at the MoMA leg of the exhibition, because the pelt is shedding, and absolutely no one wants to see a bald, leather-covered tea service.

Unlike Oppenheim’s fur-covered pieces of jewelry, which are functional objects enhanced by fur, the application of fur to the tea service renders it dysfunctional. Similarly, when Man Ray attached tacks to a flatiron to create The Gift (originally 1921), a common, utilitarian object was transformed into something that would shred the fabrics it had formerly smoothed out. Ray made an iron into an object of menace.

Meret Oppenheim, “Object,” 1936, fur-covered cup and saucer. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Oppenheim’s cup is so cheap that one can see air bubbles on the handle. And why has the entire handle not been covered in fur? It is a slipshod coating of fur. The fur that covers the cup is particularly rough and coarse — compare it to the finer fur on the saucer. In person, it looks more ragged than in MoMA’s photographs. (Perhaps the museum has a fur stylist/groomer to give it a quick perm prior to photography sessions.)

Oppenheim glued the fur haphazardly, such that it juts upward around the brim. This tea service is quite a contrast to Oppenheim’s bracelet, which was carefully crafted by Schiaparelli. Oppenheim has given us a shaggy tea service — especially the cup and spoon —specifically in the parts that one puts into their mouth. The deliberate coarseness of the cup and spoon endow them with a very aggressive character. The ritual objects of the “civilized” (smooth and refined) tea service have been rendered “savage” (wild and untamed) by the inexplicable growth of fur.

Installation shot of the Surrealist Objects exhibition at Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris, 1936. Photo: SmartHistory.

Oppenheim’s fur covered tea service is in the center of the lower shelf of the vitrine in the above photo, beneath Duchamp’s readymade bottle rack. Picasso’s Glass of Absinthe (1914) is on the extreme right of the middle shelf, and Salvador Dalí’s Aphrodisiac Jacket (1936) —with attached shot glasses — hangs on the right.

Charles Ratton was the leading Parisian dealer in African, Oceanic, and Native American objects. The exhibition featured natural objects, found objects, works created in the Dada and Surrealist orbits, as well as “Savage objects” (Oceanic and Native American works).

The catalog for the exhibition refers to Oppenheim’s piece as Object. Fur-covered Cup, Saucer, Spoon. In his Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism in 1938, Breton renamed it Le Déjeuner en fourrure (Luncheon in Fur), a clever synthesis of Édouard Manet’s painting Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass, 1863) and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novel Venus in Furs (1870). (Richard von Krafft-Ebing utilized the latter to define sexual masochism.)

Breton’s title implies psycho-sexual intentions and readings that were not part of the artist’s original conception. It is often stated that Oppenheim preferred the title Object, and in interviews she seems to disapprove of Breton’s title. But in a questionnaire for the Museum of Modern Art in 1975, Oppenheim declared: “both [titles] are correct.” So we will let that serve as her ultimate word on the subject.

The hairy tea service elicited strong responses from viewers, who found it startling, disturbing, and even offensive. One woman fainted in front of the piece in New York in 1936. It is likely that Object powerfully suggested oral sex to some of the most deeply affected viewers, but on a level that did not register consciously. Many commentators, like Nina Martyris, put it in a Freudian context: “This being the age of Freud, a gastro-sexual interpretation was inescapable: the spoon was phallic, the cup vaginal, the hair pubic” (“‘Luncheon In Fur’: The Surrealist Teacup That Stirred The Art World,” NPR, Feb. 9, 2016).

Oppenheim did not intend the readings that have become attached to Object. When an art dealer wanted to create a multiple edition of this work in 1970, Oppenheim refused, saying it was “more idea than object” (interview cited by Lanchner).

The full significance of a work of art, of course, is not limited to the artist’s original intentions or ambitions. Nor does the relative amount of thought, planning, or labor that is expended in the fabrication of a sculpture determine its importance. Apparently, the idea for Object came from off-hand remarks made by artists who admired Oppenheim’s fur-covered bracelet at a café. Similarly, Ray’s The Gift was made as a present on the day of an opening, and it was not intended to be part of his exhibition. Nonetheless, it is now regarded as one of his most important sculptures (or assisted readymade, if you prefer to use Dadaist terminology). Object has likewise greatly exceeded Oppenheim’s intentions and the expectations she had for it.

We can compare Oppenheim’s Object and Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen to Alberto Giacometti’s Suspended Ball (1930-31), which is visible in the far left of the Ratton exhibition installation photograph illustrated above. In Giacometti’s sculpture, a ball with a cleft is suspended just above a crescent moon-shaped object. As one swings the ball, it forever approaches, but never quite couples with the form beneath it. Sexuality — or perhaps its perpetual frustration — is suggested in these three sculptures in ways that are both more compelling and more disturbing than in, for instance, paintings by Salvador Dalí that feature explicit imagery.

The Museum of Modern Art’s founding director Alfred J. Barr Jr. was very taken by Object. He included it in his landmark exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism in 1936-1937 that featured 700 works (see MoMA’s description). Barr, in fact, had to insist on the continued inclusion of Object. It was one of nine objects (including three Duchamps and a model of a lichen) that A. Conger Goodyear, the president of the museum board, wanted removed from the exhibition when it traveled to other venues. See the letter from Thomas Mabry to Goodyear dated January 8, 1937.

As noted above, Barr had also requested to borrow Ma gouvernante – My Nurse – Mein Kindermädchen and another work by Oppenheim for the Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism exhibition, but they never arrived in New York.

Barr noted the strong response Object elicited from viewers of the exhibition:

Few works of art in recent years have so captured the popular imagination…. The “fur-lined tea set” makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability. The tension and excitement caused by this object in the minds of tens of thousands of Americans have been expressed in rage, laughter, disgust or delight (“Surrealism: What It Is in Literature and the Arts — Its Origin and Future,” World Today: Encyclopedia Britannica (April 1937).

Barr forged the modern art canon at MoMA, but it was not always smooth sailing. He purchased Object for $50. Though this has been described as half of Oppenheim’s asking price in 1936, Dupêcher pointed out to me Barr’s letter to Oppenheim in which he says his check amounts to “well over” the 1000 francs she requested.

Oppenheim is often erroneously credited as the first woman to be represented in MoMA’s permanent collection. For this reason, Martyris notes that she is “playfully called the First Lady of MoMA.”

But the full story is more complicated. As Lanchner points out, Barr — whose advanced tastes were sometimes reigned-in by more conservative MoMA trustees — had bought Object with his personal money. Goodyear and the other trustees rejected Oppenheim’s piece when Barr proposed it for acquisition in 1936. Goodyear regarded it as one of the “ridiculous” objects in the exhibition.

So, Barr bought Object with his own money and designated it an extended loan to the museum. Barr was again rebuffed by the board when he presented Object in 1940.

In 1943, MoMA’s board chair Steven Clark (who was particularly hostile to self-taught artists) actually forced Barr to resign as MoMA’s director. The traditional story that Barr refused to leave the museum and kept working in a small office isn’t quite true, either. Barr instead took a lesser position. See The Art Story.

In 1946, Object became part of the museum’s study collection. It was not exhibited in the galleries, but it could be seen by appointment. Despite its fame, Lanchner says the work was largely “unseen” for 27 years. One important exception was Peggy Guggenheim’s Exhibition by 31 Women, which was held in her gallery, Art of This Century, in 1943. Its next public showing was in MoMA’s 1961 exhibition, The Art of Assemblage. Lanchner points out that Object was not “fully integrated into the Museum’s collection” until 1963.

Oppenheim’s Object was the star of three exhibitions in 1936, in Paris, London, and New York. Lanchner began her book with a quote from Marcel Jean’s The History of Surrealist Painting (1960), which stated that many visitors to Barr’s exhibition at MoMA “seemed to take it [Object] as a symbol of the Exhibition and of the Museum itself.” She ends the book with a poster the museum made in 2004 after a four-year closure. It features a picture of a diner with the caption “Manhattan is Modern Again.” Oppenheim’s fur-covered tea service sits on the counter. For an object that is so emblematic of MoMA and of modernity itself, it is shocking to learn just how long and hard a battle it was to bring it into the museum’s permanent collection.

Oppenheim herself came to have an extremely ambivalent attitude towards Object. It was an offhand creation that took little thought or work, yet its fame greatly eclipsed everything else she created or achieved as an artist. I’ll let Mary Ann Caws have the last word on this subject: “Meret Oppenheim is, and remains, very in your face, more so than any other Surrealist or Dada creator I know. And her Fur Teacup takes the veritable cake” (Gastronomica).

Meret Oppenheim, Fur Gloves with Wooden Fingers (Pelzhandschuhe), 1936/1984. Fur, wood, and nail polish, 2 x 8 1/4 x 3 7/8 in. (5 x 21 x 10 cm), Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland.

Oppenheim also created this eerie pair of gloves that suggests a hybrid creature that exemplifies a “wild”/“civilized” dichotomy. The fur-covered hands are at odds with the wooden fingertips that have painstakingly manicured and polished fingernails.

The exhibition also includes a study for a woman’s shoe with an open ankle and a fur-covered lower section with wooden toes and painted nails. It’s a pity Oppenheim didn’t make three-dimensional versions of these shoes. But she was loath to be categorized as an artist who simply put fur on things.

Meret Oppenheim, “Three Murderers in the Woods” (Drei Mörder im Wald), 1936, gouache on paper, 8 1/2 × 8 11/16 in. (21.6 × 22.1 cm), Private collection, Switzerland. Courtesy Galerie Krinzinger Vienna. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Oppenheim made two gouaches in 1936 that channel German Expressionist painting, in both style and subject matter. These works must reflect the traumas and anxieties of the threats posed by the Nazis (see “Antisemitic Legislation 1933-1939” linked above).

In the very roughly executed Three Murderers in the Woods, two men carry a naked body. One of them holds a lantern, while the other one blends into the blackness of the forest. The third murderer, who is dressed in white, seems to smile as he holds a club or axe. Standing ominously over a pool of blood, he is likely a serial executioner.

Corpse in a Boat features a woman viewed from above in a rowboat that is adrift in a strong current. She has been tortured. Her hands are tied behind her back, and her genitals have been mutilated. The boat is depicted on a sharp diagonal. It has been cropped at the top, which serves to emphasize the cuts made into the woman’s body.

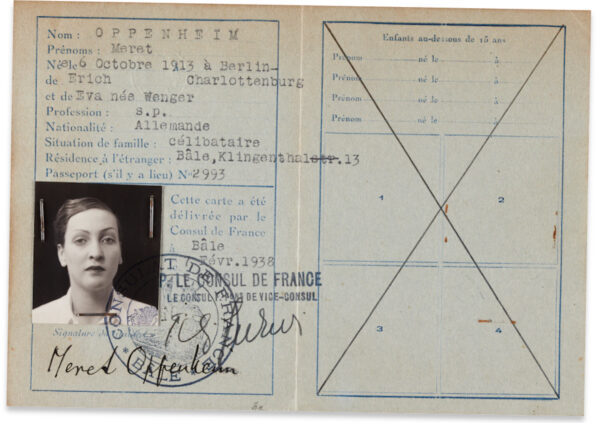

Meret Oppenheim’s Carte de Tourisme, dated February, 1938. Photograph: Kunstmuseum, Bern.

I regard the three paintings from 1936 discussed here as among the finest Oppenheim produced during her long career. The three objects from 1936 are her very best (along with The Pair, 1956). We can only imagine what might have transpired if her remarkable artistic momentum had not been interrupted by the Nazis and World War II.

Oppenheim in Switzerland

Meret Oppenheim, “Stone Woman” (Steinfrau), 1938, oil on cardboard, 23 1/4 × 19 5/16 in. (59.1 × 49.1 cm), private collection. Photograph: MoMA.

Stone Woman is largely rendered by colored stones that have been painted in an illusionistic manner. The depicted woman seems to be sleeping on a riverbank rather than a beach, because the water is flowing parallel to the waterline. Her head is resting on her right arm and hand. Yet, beneath the waters, we can see that she wears small black shoes and blue stockings. Above the stockings, flesh-colored legs have been painted over the stones that are underwater. It seems that water is transforming an anthropomorphic pile of stones into a flesh-and-blood woman. The painting is consistent with Surrealist concerns with instability and metamorphosis.

Oppenheim told Belton it was “a picture of contraries: sleeping stone and living waters.” She referred to the stone as “my inability to do any work.” The feet, she said, were “the only really positive thing” because they “represent a connection to the unconscious.” The unconscious is here posited as a connection to life and work.

Oppenheim’s point of departure for this painting was a Man Ray photograph of stones that she anthropomorphized in a more complete manner. The Menil Collection owns a more figurative drawing by Oppenheim that likely served as an intermediary between Ray’s photograph and the oil painting.

Meret Oppenheim, “The Suffering of Genevieve” (Das Leiden der Genoveva), 1939, oil on canvas, 19 1/2 × 28 1/8 in. (49.4 × 71.5 cm), Kunstmuseum Bern, Meret Oppenheim Bequest.

Medieval legend tells of Genevieve of Brabant, who was falsely accused of infidelity. After being spared by her executioner, she lived for six years in a forest. Oppenheim depicted Genevieve several times, and it is assumed that her forced exile from Paris (and her native Germany) led her to identify with the legendary figure.

In the above painting, Genevieve floats on a bed made of clouds and her own straw-like hair. She is naked, her arms are out of sight, and her expression seems to be one of dismay. An impish figure floats above her in a wooden cart strewn with roses.

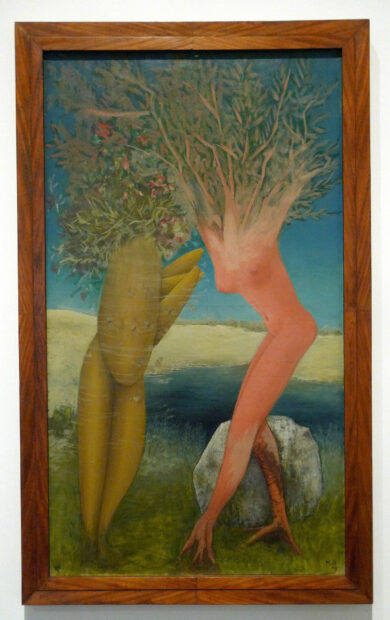

Meret Oppenheim, “Daphne and Apollo” (Daphne und Apollo), 1943, oil on canvas, 55 1/8 x 31 1/2 in. (140 x 80 cm), Lukas Moeschlin, Basel. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Daphne and Apollo is easily the best of Oppenheim’s large paintings, as well as a dramatic example of her proclivity for androgyny, which upends the traditional myth, as summarized below.

After Apollo’s insult, Cupid causes Apollo to become obsessed with Daphne, who, having pledged chastity to Diana and also subject to Cupid’s manipulations, finds him repulsive. Just as Apollo is about to catch Daphne, her father turns her into a laurel tree, to Apollo’s everlasting frustration. See my Glasstire article “Apollo and Daphne: A Tale of Cupid’s Revenge Told by Ovid and Bernini.”

Oppenheim prioritizes Daphne in the title. Her story is not about Apollo’s frustrated suffering, but rather about two evolving beings. In standard depictions of this myth, Apollo is a physically unchanging male god. But in Oppenheim’s painting, which I discuss in “Cupid’s Revenge 2: Apollo and Daphne, From Ancient Greece to Airbrushed Fantasy,” Apollo has transformed/transitioned much more than Daphne (I compare his russet brown trunk to a potato).

Meret Oppenheim, “Daphne and Apollo” (detail of trunk and head), 1943. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Moths or butterflies circumnavigate Apollo’s torso, underscoring his vegetal nature and the process of metamorphosis. They have — or their progeny will in the future — metamorphosize from caterpillars in his branches. Apollo’s head (visible at the top of the above detail) is already made up entirely of flora. It recalls some of the vegetal faces made by Max Ernst that were initially suggested by accidental effects.

Apollo has become a gender and species fluid being. I cited Juliet Jacques, who notes Oppenheim’s “androgyny of the mind” and her Jungian belief that a significant work “invariably reflects the entire human being, which is both male and female.” Instead of fleeing, Daphne turns towards Apollo, as the branches that spring from their upper torsos commingle.

Meret Oppenheim, “Daphne and Apollo” (detail of Daphne’s head), 1943. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Daphne’s head is barely discernible. We can expect her body to transition speedily as well.

Meret Oppenheim, “Primeval Venus” (Urzeit-Venus), 1962, painted terracotta with glazed straw, 20 7/8 x 10 1/4 x 7 1/2 in. (53 x 26 x 19 cm), Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Switzerland, purchase with funds from the Jubilee Foundation of the Swiss Bank Corporation.

Primeval Venus is a fascinating work that straddles the boundaries between figuration and abstraction. The straw at the top presumably represents fertility.

In the lower portion of the work, we can read the swelling in the lower center as a belly — possibly a pregnant one. The protruding forms beneath it read easily as legs — or proto-legs. At the same time, these lower forms also suggest breasts.

We can see a similar phenomenon in Oppenheim’s Miss Gardenia (1962), which consists of a small plaster-like substance in a metal frame (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). In the latter work, the only anthropomorphic form is a pointed shape in the center that could be a nose or a breast.

Meret Oppenheim, “Primeval Venus” (Urzeit-Venus), 1962. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Primeval Venus looks like it is made out of wood rather than clay. In the rear, parallel grooves have been carved into the sculpture. It follows a clay version made in 1933.

Meret Oppenheim, “A Distant Relative” (Eine entfernte Verwandte), 1966, molded substance (Rugosit) in bronzed iron frame, 10 5/8 × 9 1/16 × 6 5/16 in. (27 × 23 × 16 cm), Klewan Collection. Photograph: Artsy.

A Distant Relative (which is female gendered in the original French and German) is arguably Oppenheim’s most interesting exploration of androgyny. Like Miss Gardenia, white shapes emanate from a found frame. But the forms in A Distant Relative also escape from this frame. Two pendulous breasts descend from each side. They rest on a metal base of three bowls with a grape leaf pattern. The nipples are clearly delineated by concentric circles.

A single, very long and very thin element descends between the breasts. In her catalog essay, “Meret Oppenheim as a Contemporary Artist: Five Close-Ups, 1966-1982,” Nina Zimmer notes that the rectangular white shape inside the frame recalls underwear. If one concentrates on the central phallic element, one can even imagine the breasts as extremely drooping testicles.

This central phallic form is also reminiscent of a nose. Zimmer points out that Oppenheim referred to it on her inventory entry as a nez rougeâtre [reddish nose], though Zimmer doesn’t pursue the reading of this form as a nose on a head.

In addition to underwear, the two curving hollow forms on each side at the top suggest eye sockets. In this reading, the image is a face, and the breasts can be read as gigantic jowls.

A Distant Relative is a polymorphous image. Forms that resemble male and female genitals are unstable. They readily collapse into other forms. It is easiest to read this work as an androgynous figure. But these forms can also combine to suggest a bold caricature of a face, which one can contrast with Mrs. Gardenia, which is only the slightest suggestion of a face.

Fang Ngil Mask, 19th century, Gabonese Republic, wood, pigments, 69 cm high, Musée du quai Branly. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Could Oppenheim have found inspiration in a Fang Ngil mask, such as the one illustrated above? The hollowed-out areas on either side that form the mask’s eye sockets and the extremely long nose could have suggested the similar forms in Oppeheim’s piece. Perhaps Oppenheim emulated a Fang mask when she made A Distant Relative, and perhaps that is why these genital elements can also be read as parts of a face.

Meret Oppenheim, “Hm-hm,”1969, acrylic on canvas; oil and gold leaf on wood; bark; and carved wood, 6 ft. 6 1⁄4 in. x 37 3/8 x 3 9/16 in. (200 x 95 x 9 cm), private collection, Bern.

Hm-hm benefits greatly from collage elements. The soft, white geometric forms on either side of the blue figure are also extremely well done. The strange, moth-like form at the top (with suggestions of apotropaic eyes) and the hand with the bizarrely elongated arm on the right endow the work with unusual, attention-grabbing features. They are much more eye-catching and remarkable because they are rendered in three dimensions.

Meret Oppenheim, “Hm-hm,” 1969 (detail of top of painting). Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Butterflies and moths, as noted above, are symbols of metamorphosis. The three-dimensional wooden object serves as the woman’s head and as the body of a moth. The colorful areas on either side of it can read as the moth’s wings, or as a colorful coiffure. As one looks at this work, the moth body snaps into a woman’s head, and back into a moth body again, in perpetual metamorphosis.

In Hm-hm, the woman’s body somewhat resembles a partially folded umbrella. The blue line emanating from it suggests a handle. The three dimensional arm and the hand that holds the cane are somewhat comic elements. Additionally, this cane seems to offer crucial support, since the woman is considerably off balance.

I wonder if Oppenheim knew the work of the Mexican artist Alberto Gironella, who utilized some of the elements in Hm-hm. Breton collected Gironella, and he deemed him a Surrealist (Breton’s highest honor). In 1965, Breton judged Gironella to be one of the ten best artists of the previous twenty years.

In a number of his object-paintings and assemblages, Gironella utilized wooden female heads and hands. He loved elaborate coiffures. When he reinterpreted Diego Velázquez’s women of the Hapsburg court, Gironella often recreated their elaborate wigs with assemblage elements or with images of meat.

Meret Oppenheim, “Octavia” (Oktavia), 1969, oil on wood and molded substance with saw, 73 5/8 × 18 1/2 × 1 9/16 in. (187 × 47 × 4 cm), private collection, Bern. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Octavia is one of Oppenheim’s cleverest works. It consists of a painted panel whose left side incorporates a large saw. As Zimmer notes, the saw is known as a foxtail (fuchsschwanz). The actual saw is mirrored on the right side by a faux saw that is painted a dull metallic color. The handles of these twin saws, in turn, form the eye sockets of a figure.

Meret Oppenheim, “Octavia” (detail of top), 1969. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Though I have only seen Octavia interpreted as a female figure, I view it as an androgyne. On the left, the wooden saw handle is much larger than the corresponding faux-saw handle on the right. Presumably, the more robust actual saw constitutes the male half, while the faux saw is the female half.

Ironically, only the flat, faux-saw eye socket contains an eye — a human one that is painted a vivid blue. Perhaps this blue eye is a reminiscence of René Magritte’s Portrait (1935), which features a blue eye in the middle of a slice of ham on a plate.

The implication of these gendered differences in Octavia might be that men are bigger and more robust, but women are more insightful and visionary.

Beneath this pair of eye sockets, Oppenheim has modeled a three-dimensional nose. Beneath the nose, the artist added a protruding tongue that seems to lick the junction of the wooden saw handle and the blade.

The lower part of the panel consists of a faux tree trunk that is painted to simulate bark. So the conceit of this work is that it has been hewn, carved, and painted out of a still living tree. Perhaps it is meant to represent a hybrid creature or a dryad. In this respect, I see many parallels to Oppenheim’s Daphne and Apollo.

In 1967, Oppenheim made a beautiful mixed media work called Forest Interior with Dryads (it is in the exhibition). Thin, twisting forms are painted in oil on unprimed canvas. They represent tree trunks, and are a little bit reminiscent of some early forest interiors by Gustave Klimt, such as Pine Forest II (1901). Oppenheim’s trees, however, are considerably more abstract. Over these trees, Oppenheim added a few pieces of oak bark and molded substances to represent the dryads.

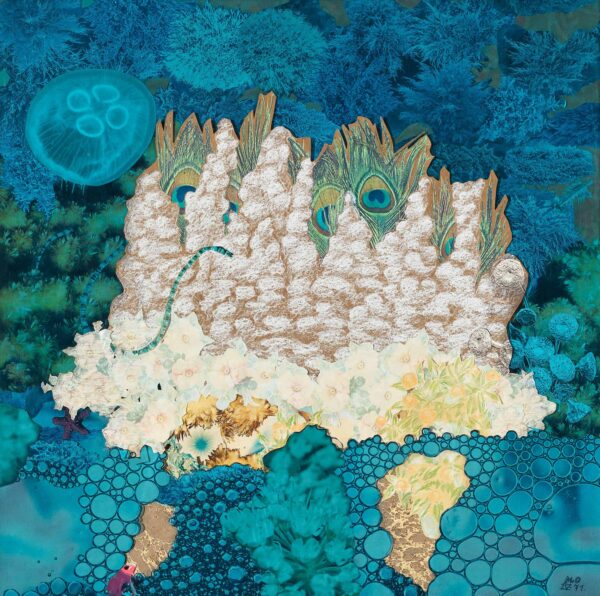

Meret Oppenheim, “Octopus’s Garden,” 1971, collage and blue film, 21 7/8 × 21 7/8 in. (55.6 × 55.6 cm), private collection.

I presume that the title of this beautiful collage was inspired by the Beatles song of the same name that was featured on the Abbey Road album, released in 1969.

Meret Oppenheim, “Garden Spirit” (Gartengeist), 1971, carved wood and palm fibers, 22 7/16 × 5 7/8 × 7 1/16 in. (57 × 14.9 × 17.9 cm), private collection, Switzerland, courtesy Koller Auctions. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Out of wood and palm fibers, Oppenheim has created a Western counterpart of a tribal sculpture of a god or spirit. Oppenheim’s spirit is meant to preside over a garden. Fittingly, it possesses an anthropomorphic form that resembles a shovel.

Meret Oppenheim, with Anna Boetti and Roberto Lupo, “Man Walks Away,” 1971, various materials, 19 11/16 × 12 5/8 × 8 7/8 in. (50 × 32 × 22.5 cm), Bürgi Collection, Bern. Photograph: Kunstmuseum, Bern.

This fascinating object reminded me of early Miró. It struck me as something done in the spirit of Surrealism.

It was created with Anna Boetti and Roberto Lupo, as a three-dimensional exquisite corpse. This was a collaborative Surrealist technique in which each artist made a section of a drawing after seeing only a fraction of a section made by someone else.

Meret Oppenheim, with Anna Boetti and Roberto Lupo, “Man Walks Away,” 1971, various materials, 19 11/16 × 12 5/8 × 8 7/8 in. (50 × 32 × 22.5 cm), Bürgi Collection, Bern. Photograph: Kunstmuseum, Bern.

When I initially glimpsed the object at the Menil, I did not realize that it possessed an anthropomorphic head and little arms.

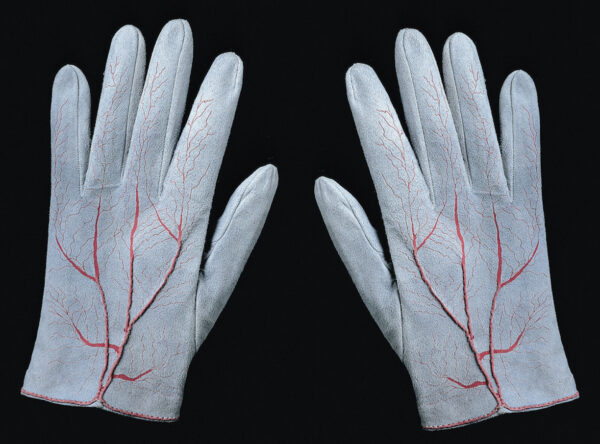

Meret Oppenheim, “Pair of Gloves” (Handschuhe [Paar]), 1985, suede goatskin with silkscreen and hand-stitching, 1/16 × 5 5/8 × 3 1/2 in. (0.2 × 21.3 x 9.3 cm) each. Photograph: Parkett.

The red color and the three-dimensional stitching replicate the blood vessels in living hands. Though these are empty, inanimate gloves, they carry the sense of the lifeblood that flows through human hands. To a degree, the red vessels also suggest roots, the veins in plants and trees, rivers, and other liquid pathways that make life possible.

As a final example of the Man Ray-Meret Oppenheim dialogue, Oppenheim’s New Stars (1977-82), which closed out the exhibition at the Menil Collection, is strangely reminiscent of Ray’s Observatory Time: The Lovers. The latter was painted in1936, Oppenheim’s most extraordinary year in Paris. Both paintings feature geometric shapes that float above a sliver of landscape at the bottom. For Ray’s pair of giant, rouged lips, Oppenheim substituted geometric forms. Perhaps her painting was an abstracted, good-bye kiss to her former lover, who died in November of 1976, and to the Paris she knew in the 1930s.

Conclusion

Surrealist currents ran through Oppenheim’s oeuvre all the way to the end. I am personally drawn to the works that most directly continue Surrealist subjects, themes, techniques, and modes of inquiry. Oppenheim didn’t want to repeat herself, and she didn’t want to be pigeonholed. Additionally, she always wanted to be receptive to new forms of contemporary art.

Oppenheim’s interest in dreams preceded her exposure to Surrealism and they served as a source of continuous inspiration. Surrealists sought to reject logic, rational categories, bourgeois conventions, and bourgeois lifestyles. Oppenheim’s enthusiasm for continuous experimentation and inquiry should be regarded as consistent with the core principles of Surrealism — particularly in comparison to the rather conventional and professional choices that most of the other Surrealist artists made when they chose to spend their lives perfecting a recognizable style. Oppenheim always defied rational and practical “careerist” expectations.

Oppenheim embodied freedom of artistic inquiry. She created spontaneously, without a fixed path, with mixed results. Her mixed media works are always more interesting than her geometric paintings. I don’t think she ever refined her painting skills enough to make high-quality hard-edged geometric forms, and paintings with those qualities usually fall flat. The Secret of Vegetation (1972), for instance, can’t hold its own in comparison to Hm-hm (1969) and Octavia (1969), all of which hung in close proximity in Houston.

I am very grateful to have finally seen a large body of Oppenheim’s works (including the less successful ones) at the Menil, where they were beautifully installed.

Dupêcher noted to me that the Menil is “thrilled” by the public response to the exhibition, as well as the press it has received. I trust that the exhibition will also be a revelation to many visitors at MoMA.

Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition was on view at the Menil Collection in Houston from March 25 – September 18, 2022. The exhibition is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from October 30, 2022 – March 4, 2023.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.

4 comments

Knockout article, very enjoyable read!!! Bravo!!!

Thanks, Roberto. I enjoyed the exhibition, and the opportunity it afforded me to think about her work. I was surprised to find how little reliable information on Oppenheim is readily available.

Bravo Ruben! What tome! I’ve been a collector of M.O. work since 1988. I saw her exhibition at the Kent Gallery and bought about eight works, several of which are in the current show. One work they refused to include was “Bon Appetit, Marcel”, 1966, which has been in all of her exhibitions and has garnered a good hundred pictured reviews. I have no idea why they did not want to include this iconic sculpture. MOMA illustrated it in 2018 in their “Object” catalog on Meret Oppenheim.

https://www.wired.com/2014/02/meret-oppenheim-retrospective/

Here is a video presentation from 2013 from the Vienna Kunst Forum retrospective with archival footage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pK31yKscGYc

Thanks, Foster. And congratulations on your collection. Curators of retrospectives want a core of “must-have” works. At the same time, they want to shake things up, to look at things in different ways, and to avoid having the exact same works as previous retrospectives. Thanks also for your links.

Ruben