Installation view of “The Iconic Portrait Strand” by Nestor Topchy at the Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Paul Hester.

Believe it or not, more than one hundred artists and their friends have been camping out inside the Menil Collection’s Main Building for over three months, and they show no indication of leaving anytime soon. I am talking, of course, about the artists depicted in Nestor Topchy’s gold-leafed portraits of friends, acquaintances, and cultural luminaries that currently line the walls of one of the Menil’s galleries. Topchy made the small yet pronounced paintings using a technique typically reserved for religious icons but, perhaps in defense against accusations of blasphemy, Topchy claims no direct correspondence between the religious artistic tradition and his own iconic portraits. However, the works do nest cozily among the Menil’s collection of Byzantine icons one gallery over, albeit with a distinctly modern and populist flare.

So how iconic are they? To my eye they correspond with what Bishnupriya Ghosh calls the “bio-icon,” or living image, which is an image of a person who has been transformed into a signifier for a collectivity of one sort or another (1). Unlike religious icons, which play a significant role in organizing social customs around religious ceremonies, bio-icons can facilitate social behavior by forming imagined communities united by an ethos that could be secular or political in nature. In the case of Topchy’s community, the social body he has imagined shares a cultural DNA, which appears to be one united by the city of Houston, Topchy himself, and the uniformity of his iconic aesthetic.

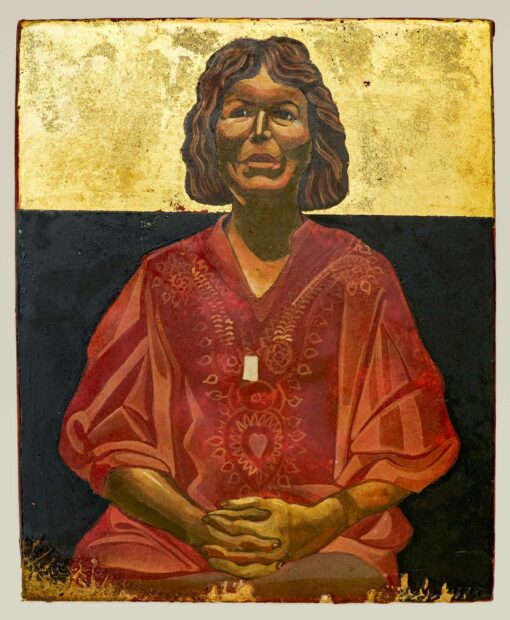

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Terrell James),” 2008–23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy, Photo: Caroline Philippone

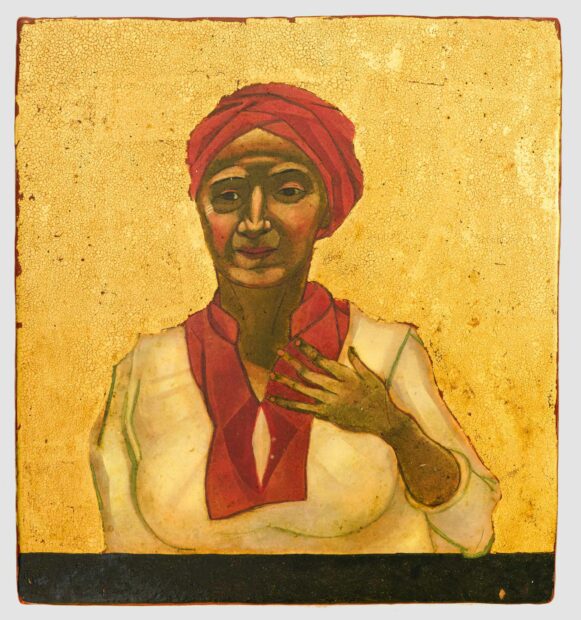

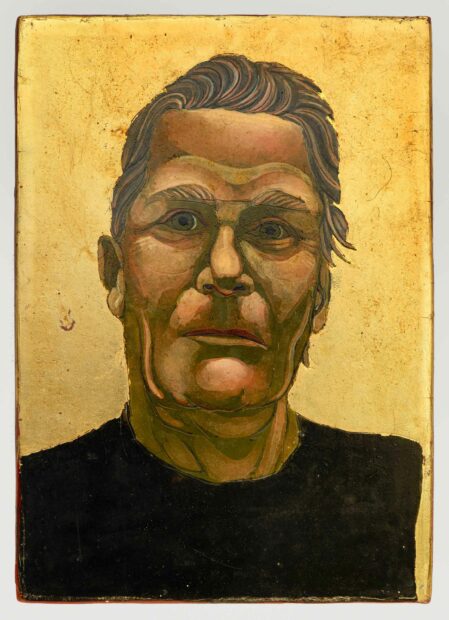

The stylistic consistency of Topchy’s portraits brings each subject under the fold of the project’s umbrella. Like the painterly techniques of Thomas Hart Benton, whose rhythmic linework and dramatic contrasts between light and dark united disparate themes of early twentieth-century American life, Topchy’s brushwork conforms each subject to an aesthetic idealism. For example, garments worn by many of the sitters have been rendered with dramatically angled folds that add dynamism to an already eye-catching image made bright and bold by way of its gold-leaf background. The face of nearly every subject has also been rendered with tiny white lines around the eyes and cheeks that constitute ozhivki, or what Topchy calls “life giving lines,” a feature commonly found among traditional icons (2).

Installation view of “The Iconic Portrait Strand” by Nestor Topchy at the Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Paul Hester.

The Iconic Portrait Strand’s emphasis on figures who have a meaningful connection to Houston appears unique within the Menil Collection, a museum that has largely consisted of objects made by people from other parts of the world. Topchy’s portraits bring to the fore the humanity of the figures so that they are known first by their visage rather than their work or social position. When I encountered David McGee’s portrait, for example, my first thought was not of his paintings, but of encountering him the week before, when he gave a public talk about his latest exhibition at Inman Gallery.

Or take, for example, Rick Lowe, whose countenance Topchy has rendered as thoughtfully observant but contemplating action. The air of active curiosity that permeates Lowe’s portrait takes on a depth of historical resonance when coupled with the fact that Lowe, together with seven artist collaborators, saw a need for preserving the cultural history of Houston’s Third Ward and then went on to co-found Project Row Houses. There is also here within the “strand” Houstonian Terrell James, an artist and original board member of the local arts nonprofit DiverseWorks, who, like a visionary leader, looks out toward a world beyond the pictorial one her likeness inhabits.

My sense, from observing the collection Topchy has assembled, is that these are not only some of Houston’s artistic movers and shakers, but the kind of people who keep the lights on at the city’s cultural institutions. As otherworldly as each portrait appears at first, each one also redirects attention back to this world, suggesting one might very well encounter the person behind the portrait out and about in Montrose or on the Eastside. And with over one hundred individuals represented, the opportunity for a chance encounter seems even greater.

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Arielle Masson),” 2008–23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy. Photo: Caroline Philippone

A handful of portraits portray figures that Topchy never personally knew or are no longer alive, but whose significance seemed relevant either to the artist or the subject, like the Irish dramatist Samuel Beckett, the Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky, and the French artist Gustave Moreau. But the portrait of Walter Hopps — the Menil Collection’s founding director — offers a key to deciphering the mixture by harking back to a particularly egalitarian era in the museum’s history (3). Hopps was well-known during his time in Houston for socializing with local artists, and for sometimes collecting or mounting exhibitions of their work at the Menil. During Hopps’ tenure, solo shows were given to Texan artists like Ben L. Culwell; the Menil also mounted its first deliberately Texas-themed group show (called Texas Art), which showed the work of Houstonians like Jim Love and suggested that the Menil could provide a platform for Houston artists. The Menil under Hopps’ directorship not only brought ambitious art to Houston, but championed Houston artists, which happened more frequently after Hopps left. Topchy’s portraits emphasize the person behind the painting as well as the relationships and communities that contribute to Houston’s artistic culture.

Nestor Topchy, “Iconic Portrait Strand (Walter Hopps),” 2008–23, egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood. Courtesy of the artist, © Nestor Topchy, Photo: Caroline Philippone.

By illuminating artists, gallerists, cultural workers, and preservationists, as well as friends and acquaintances, Topchy has drawn attention to a social network that emanates from within Houston’s cultural landscape. Each portrait within the “strand” appears iconic, as if it has formed a portal to another world, but it also signifies one node within a much larger social body. If the Iconic Portrait Strand facilitates the formation of an imagined community, it is also an invitation to imagine a community that may already exist.

Installation view of “The Iconic Portrait Strand” by Nestor Topchy at the Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Paul Hester.

The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy is on view at the Menil Collection in Houston through January 21, 2024.

Texts Referenced:

1. Bishnupriya Ghosh, Global Icons: Apertures to the Popular (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 12.

2. Pavel Florensky, Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art (London: Reaktion, 2002), 301.

3. Kristina Van Dyke, “Losing One’s Head: John and Dominique de Menil as Collectors,” Art and Activism: Projects of John and Dominique de Menil (Houston: Menil Foundation, 2010), 134.