Rabéa Ballin is a multi-disciplinary artist who has been a key member of the artist community in Houston’s Third Ward for many years. She is also a part of the Roux Collective, with Ann Johnson, Delita Martin, and Lovie Olivia. A day after the opening of Project Row Houses’ Round 53, The Curious Case of Critical Race… Theory?, where she is exhibiting an installation as a part of Roux, Ballin and I had a chance to talk about the connection between her early and recent works around themes of place, identity, and their relationship to form and politics.

Liz Kim (LK): I wanted to start off by talking about some of your early work from 2009 and onwards. Could you tell me about the series Fresh?

Rabéa Ballin (RB): I graduated in 2006, and during my last semester at grad school I saw Okhai Ojeikere’s photographs at the Blaffer Museum. Most people know that I was raised learning how to do hair in my mom’s hair salon. When I saw the Ojeikere photographs, it was the first time I looked at hair as sculpture. These are ceremonial hairstyles that identify roles within a culture, Nigerian culture specifically. It changed the way I looked at my experience with hair. I was at a point of leaving graduate school where I really wanted to make work that was about myself and my own experiences. A lot of people ask me why hair braiding or Black hair imagery. And it’s because of my personal experience with it — I was braiding in college.

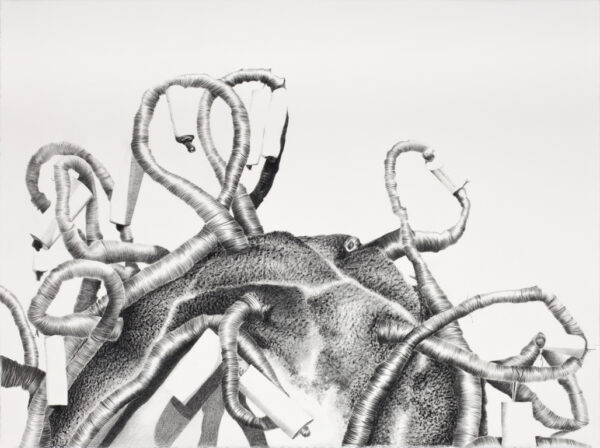

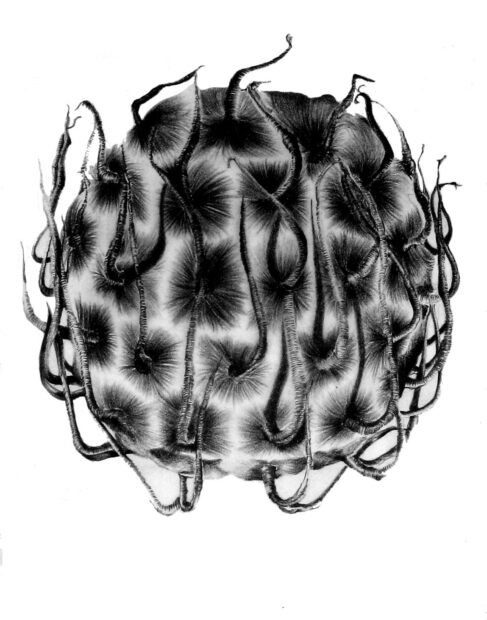

Rabéa Ballin, “Untitled,” 2009, black prisma on paper, 22 x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

LK: Was that at McNeese State University?

RB: Yes, I braided on the weekends to earn gas money. It was my “other” thing, my craft. But, at the time, I didn’t think of it as my art. I saw Ojeikere’s photographs, and I was like, “Oh, wait, I braid.” So I began documenting the hair braiding. In this first series Fresh, I’m remixing his photographs. It was the first time I had such a meticulous approach to drawing hair. I changed my perspective, and I zoomed in. I’ve never drawn portraits of faces. I developed my portraiture into drawing the backs of people’s heads. That’s where you see the hair, and I didn’t want to personalize my portraits by focusing on who these individuals were. It was more representative of other things.

LK: That’s also a conceptual part of your practice. One of the unique things about his photography is that subjects are anonymized.

RB: Yeah, absolutely. I see myself as a documentarian, and also an image maker. I want to take responsibility for the images I put out, and I saw these natural hairstyles —that trend towards natural hair — in the 90s, especially as it pertained to African American women, but I felt that the imagery was underrepresented. Hair eventually became a focus of my work because I had been around it so much. I feel it. I braid it. I understand the dexterity it takes to twist and plait. The Fresh series was my first solo exhibition, and it had to be these hair drawings because I was trying to find who I was in my practice, and blending that history of hair.

Most of the images of hair that you see in my work currently are my own. I knew that I wasn’t going to always continue appropriating Ojeikere’s work. From then and moving forward, it was a self-discovery of how hair is still an important element of the work. It always is, because I still braid. I photograph my own hairstyles, then I zoom in closer and closer, and then the hair becomes abstractions.

Also, Fresh has a set of photographs that went with it, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston just bought them for their permanent collection. It says the word “fresh.”

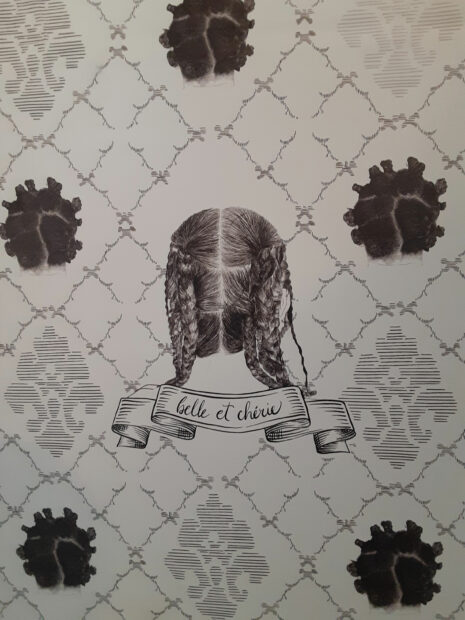

Rabéa Ballin, “coincoin,” 2011, lithograph, 15 x 11 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

LK: How did you connect with the history of Marie Thérèse [Coincoin]?

RB: I have a Creole dictionary at my house. If I remember correctly, I was just flipping through it, found a trigger word and maybe searched it, then stumbled across her story.

LK: You added several other elements to your interest that began with Ojeikere’s work.

RB: Even though I alter his images, he’s talking about his specific culture and I don’t have a personal connection to Nigerian hair. I don’t want to misrepresent myself, those drawings came from a sincere desire to acknowledge and celebrate him. But it gave me the permission to use hair as a subject, to do something similar, to archive what’s in front of me. So that’s very important because people often ask why do I work with imagery of African American women primarily when it’s actually not.

LK: Yeah, I mean this is where you were going, from Nigeria…

RB: …To Louisiana, in some cases Houston, and with the Caucasian women from the Caucasus mountain region. I work with multiple nationalities, which is a direct result from my experience at my mom’s beauty shop that tended to all races.

LK: Hair International.

RB: Hair International, and it was near a military base. When you grow up in a military community, there’s a sense of social acceptance and understanding that your peers come from culturally blended families. Racially blended families are a common thing. My dad is Mexican. My mom is German, first generation German. Our first language at home was German. But we were stationed in southern Louisiana and I was primarily raised there. Now there are, but at the time there were no Hispanic communities near there, other than the families that were in the military, who were mainly Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, and Mexican. All those cultures are represented, but as far as in civilian life, it was Black or white and extremely segregated.

My mother and I lived in a Black neighborhood on Martin Luther King Street in a small town called DeRidder, Louisiana, which was very much segregated at the time. Her beauty shop was on a corner. I would overhear comments about my mother, that she was cool, but lived in the quarters. They weren’t referring to “military quarters,” it was a derogatory term — now outdated — about the section of town we lived in. It conjures up the ‘“French Quarter,” which ties into the story of plaçage that I have explored. Specifically, the location of quadroon balls.

There’s no connection to my Hispanic roots in Louisiana where I lived, so I embraced the cultures that I was around. Do your best, and get out of here. And that’s what I did. When I got to college, I made it a point to double minor in Spanish and German. I’ve always wanted to make a connection to my personal upbringing, but I wasn’t raised in that environment, so it’s been a mixture of a lot of influences, which is what Louisiana is. The blending of many cultures — Cajun, Creole, Spanish, French, Haitian.

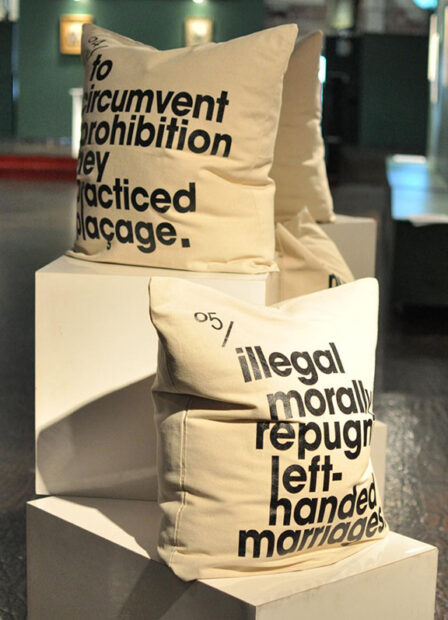

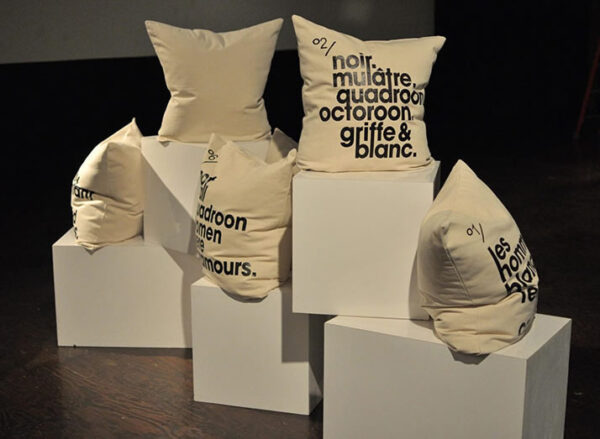

Rabéa Ballin, “#sixwordstories Chapters 04 & 05,” 2012, silkscreen on canvas, 25 x 25 in. each. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

LK: The next series is the History Slept On series (2012), through which I also see a point at which your practice becomes more political around 2011.

RB: Survival was heavy on my mind then, You know, I’ve been through a lot. I’m tired. Katrina, Rita…each disaster affected me directly. I wasn’t in New Orleans for Katrina, I was in Houston for Katrina. I went to the Astrodome and I braided hair.

I was a grad student, and with a friend of mine, Lisa, and we were like “let’s go to the Astrodome and see if anybody wants their hair braided.” And they did, Black and white. Because they were disheveled, traumatized, and they wanted their humanity back. They wanted their dignity back, and hair and beautification practices gives you that.

A lot of the work is about access or lack thereof. People were angry, in distress, and for a few moments they were able to sit, get their hair braided, have a conversation, calm down. and tell their story. It was a lot, and I left that experience recognizing hair is political.

LK: When you started digging and bringing research and history into your work, you also brought text into your work.

RB: Triggering words. Words like: miscegeny octoroon, quadroon, these supercharged words that I love.

Rabéa Ballin, “#sixwordstories,” 2012, silk screen on canvas, 25 x 25 in. each. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

I love the power of words. Words are so intimidating. I like the beauty of letters, typography as shapes and forms, but my goodness, words are powerful. That came together in Six Word Stories. I challenged myself to tell the history of plaçage, in six words. I loved it.

I wanted to do the art equivalent of what Public Enemy was doing — I started looking at David Hammons, Adrian Piper, Coco Fusco — they weren’t necessarily making in the way I thought my art had to be. Black contemporary performance art was a huge influence in being able to create work.

LK: Your History Slept On series continues with the Original Dimepiece series (2013).

Rabéa Ballin, “Collection of Circassian Hair Serums,” 2013, digital print, handmade paper, vintage glass, relief seal, 8 x 12 in. each. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

RB: This is the story of the Circassian Beauties in the American Sideshow. I started reading and researching Circassian women. What does that word mean? The Caucasus mountains — what region is that? Then, Barnum and Bailey, I found a letter that he wrote to his guide, searching for these Circassian women. It led to sex trafficking during the Ottoman Empire. That led to the appeal of these women. He had them doing snake charming, and at the end of the day he had girls from Jersey. He changed all their names. They have these ‘Z’ names, like Zula, Zenobia, which are just fetishized, exoticized names.

This series captures that very complex idea of race and identity, and the whole purpose of Barnum showing these women because of their supposed racial purity, a pseudoscience. That was a construct, a performance in exoticism, that people bought into and paid $0.10 for. And this is another pop culture reference and hip-hop reference: the dime piece. If you have a dime, that means you got a girl that’s perfect, ‘you got a dime.’ We rate our beauty based on a scale of one to ten. That was just a jackpot for me. That fakeness of it, the fake within the fake. But the story of humans as curiosities is real.

LK: Going back and forth between these different modes, to these drawings from 2014, back to the fundamentals of drawing practice.

Rabéa Ballin, “Untitled (green),” 2014, lithograph, 30 x 22 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

RB: Yeah, that flip. It went from very cerebral, to “let me go back to what I know.” Or that I’m familiar with that’s not as heavy. Let me go back, and let me bring in some color. Not too much. Let me keep it monochromatic, but I’m going to play with color and that’s just what happened. I was very intentional.

LK: The imagery itself, it’s very reminiscent of your work in your Fresh series.

RB: Yeah, they’re revisiting or remixing those for sure.

LK: And now we’re going back to your conceptual and critical work here in 2014.

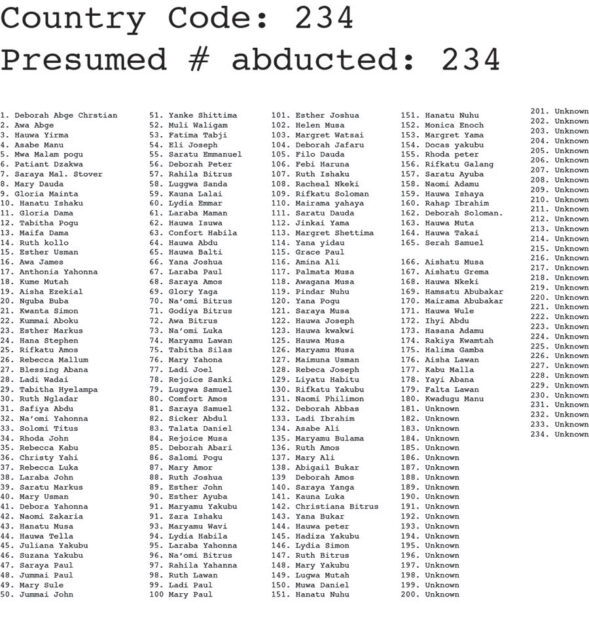

Rabéa Ballin, “Country Code 234,” 2014, text installation. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

RB: Yep, and this is the summer because this is another Roux exhibition, Suga. We showed at BLUEorange Gallery. The name of the show references the number of the Nigerian girls said to have been abducted. Those numbers changed; this was the initial report that I got. It just so happened to be the country code of Nigeria. Some of the names, half of them aren’t even there. They’re unknown, unknown, unknown. I just really felt just personally drawn to them because of my own experience of walking to school alone and the fear of being kidnapped.

LK: Also, your interest in Nigerian culture with Ojeikere.

RB: Yes, I’m tying those threads together in these pieces. There’s something cold and very dismissive when you’re just a number. So I’m adding names if I had them, adding parts of imagery if I had it. The repetitive work of cutting circles by hand, I don’t really know why that felt good at the moment or why that felt right. It was just a very methodical thing to do and sometimes doing things repeatedly brings comfort in the same way that my drawings bring me comfort. I felt like I was doing something when there’s nothing you could do.

LK: Yeah, and you have the material remnants.

RB: I just wanted to make the viewer uncomfortable, having to tiptoe around these mounds that were all over the floor. It had a performative aspect in that sense.

LK: With Project Row Houses’ Round 41, What is Natural (2014), what was the significance of this exhibition?

Rabéa Ballin, “What is Natural,” 2014, installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

RB: Lack of access to beauty products. From my experience from Hurricane Katrina, I had these little cases, medicine cabinets placed around the house with free beauty products for the community to take, and I had a discussion with people that centered on the age they were when they realized they were beautiful or had sparked someone’s interest based on physical beauty.

It was interesting — the conversations went from “I was 30 before I ever felt beautiful” to “I was eight when I felt over sexualized and gawked at by adult males.” Then we talked about hair. We shared stories about why stigma is attached to hair and how this is the only part of our body that we can change the most on a daily basis if we choose to. It’s this ephemeral material that grows out of our head that we can mold and shape and form, and when we can’t, we have anxiety about whether or not we feel beautiful. Some women feel beautiful after they shave their head. Some women only feel beautiful when they add in hair. It’s a very open conversation that I loved having.

We included my mom’s hair dryer in the show. We also pasted life-size images of my neighbor at the time, who was a hair braider in prison. We had a conversation on beautification practices within the prison industrial complex, which was a great.

LK: Then we have the show, Salt (2017), with Roux.

RB: That’s when my world of collage, hair and photography came together. I started doing digital collages with the intention of drawing them, which I did for some, but I also came to a place where I was like, “these are kind of dope, just as digital collages.”

Rabéa Ballin, “Remixing Delphine,” 2017, digital image, 18 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

That’s when I met Leslie Moody Castro in 2017 for the Texas Biennial. I had printed the digital collages on metal just to see what they looked like, and those are the ones she liked. I had them printed at Burning Bones Press. They are the digital images, but they also live as prints on paper and on Mylar.

LK: This series once again sees a transformation of your practice.

RB: Yeah, the transformation was totally experimental. There was no agenda. It was just me playing around, giving myself the permission to just show the object — don’t draw it if you have the object, why turn these into drawings if you don’t have to? They’re my photos, so I’m allowed to use them however I want. It’s knowing when to stop.

LK: Now we’re getting into your recent works.

RB: In 2020, I started drawing in my studio at home. I need to draw. Let me just give myself the hardest thing I could think of. It looks like a meteor going through space.

Rabéa Ballin, “Think of Me,” 2011, solar plate etching, 15 x 11 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

All of these photographs came from COVID, during which everyone documented the backs of their heads after not having access to getting our hair done for months (including myself) and loving it. For many years I very rigidly slicked my hair back in a bun — that was only because I’m the product of a mother who owns a hair salon, and I’ve had every hairstyle on the planet. I was tired and I was going for job interviews, and my mom said “just slick your hair back and put it in a bun.” I did, and that became my go-to hairstyle for years, until COVID, when I started wearing my hair down. I know it’s not down at this moment, but it’s either braids, or frizzy braids, or hair down. I love the freedom that COVID gave us with all of that. I read a lot of positive feedback on the flip side of not having access to beautification rituals and/or beauty shops, or simply embracing the fact that you’re going gray.

LK: Something that Leslie brought up was how, from her perspective, in your work around this time you started to get more ‘kitschy.’

RB: I love the word kitsch.

LK: She noted that with your recent work, particularly the Cluley Projects show in Dallas in 2021.

Rabéa Ballin and Sara Cardona, “Soft Veneers and Fresh Cycles,” 2021, installation view. Courtesy of the Artist and Cluley Projects, Dallas. Photo by Kevin Todora.

RB: Kitsch is a word that I was raised hearing a lot. Germans use that word kitsch. When I hear the word kitsch, I don’t think of it as an art subculture. When I hear the word kitsch, I hear my mom saying kitsch, like “it’s tacky.” Of course I love that, permeating those spaces with what might be tacky. That’s me addressing the elitism of things. When Leslie and I worked together, that was very much our intent. What if we take a little bit of lowbrow into the highbrow.

LK: With your current installation here at Project Row Houses with the Roux Collective, could you talk about how everything comes together?

RB: This has been a great building up to where I’m at now. We’re celebrating ten years in the game as a collective (we’re in our 11th year), and I see my progression. I don’t consider myself separate from the Roux Collective any longer, when I did at first. I had my personal practice, and I had Roux in the summer. Not having gallery representation anymore and attaching myself to Roux was a very important personal event for me. I have the support of my sisters to give me critique when I need it. Just being around them and doing a very grassroots effort of showing, as we do everything ourselves. We publish, we design our own books, then we all go in our separate ways and have our own separate careers. But we’re all still part of Roux.

Rabéa Ballin, “The Drawing Room,” 2022, installation view. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright Rabéa Ballin.

For this show I just wanted to show that progression, who I was in the beginning and where I am now. I brought everything together — so I’m making drawings, but they’re digital. I’m referencing history very directly, using the patterns of my mom’s couch back home in Louisiana in my wallpaper. I’m giving a nod all the way back to Marie Thérèse with the tobacco, but using the materials I’m using now with my photography, which is perforated vinyl. Everything came together for me for this one — my hair drawings and my digging into the lost stories of early Creole writers, musicians, poets, artists, and craftsmen of the period. My wallpaper is an homage to African women, European women, and Latina women. Everything together as a blend: and that’s my definition of what Creole is. My experiences, they all came together in this house.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

3 comments

Rabéa rocks!

She sure does…and so does her work!

Don’t miss her piece on view in the Looking Back show at Cluley Projects in West Dallas.

#2123Sylvan