Claude Monet, Boats on the Beach at Étretat, 1883, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

In his 1960 essay, Modernist Painting, Clement Greenberg writes, “With Manet and the Impressionists the question ceased to be defined as one of color versus drawing… and became instead a question of purely optical experience as against optical experience modified or revised by tactile associations.”

Greenberg’s claim that the essence of Impressionism lay in its reduction of painting to a recapitulation of merely optical sensory impression might be attributed to his own obsession with materiality, but it seems confirmed by the critic Jacques de Biez when, writing about Manet in 1883, asks, “Should Manet be blamed for the care he seems to have taken to repudiate in his oeuvre all psychological intention or every philosophical subject? [Manet’s] highest ambition was to remain a painter in the full plastic meaning of the term. Manet was an eye rather than a reasoning.”

Whether either claim is strictly true or not, the critical consensus now and in the late 19th century is that the nature of Impressionism’s radical break with thousands of years of artistic tradition lay in its rejection of painting’s subservience to religious and political narrative and its simultaneous elevation of painting’s innate materiality to the principle upon which the discipline should exclusively be built.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s current exhibition Monet to Matisse: Impressionism to Modernism from the Bemberg Foundation, provides viewers an opportunity to revisit the radical Impressionist proposal that painting should strip away religious, philosophical, even psychological meaning and limit itself to functioning as a simple record of biological optical impressions. Ending with Pierre Bonnard’s despairing 1945 Self Portrait, the exhibition moves chronologically through the many short-lived early Modern reactions to Impressionism’s materialist project. With highlighted snapshots of important work from the Symbolists, the Nabis and the Fauves, early 20th century European painting is seen as not as a series of advancements or linear developments but primarily a series of counter-revolutions against Impressionism’s radical break with painting as a servant to religious, political and philosophical narrative.

Charles Blanc, an art critic in the circle of Georges Seurat, sums up the early Impressionist view of art’s material primacy over its mimetic function when he argues that the imitation, or representation, of natural reality can no longer be considered the aim of art and that “…so far from art revolving round nature, it is nature that revolves around art, as the earth round the sun… .” Blanc’s distrust of mimesis is founded upon the view, increasingly popular from the time of the late Enlightenment, that artists (or anybody else) can no longer claim to have unmediated access to reality.

Human perception is filtered solely through the material apparatus of the body just as it is for the spider or the earthworm. In this view, there is no way to gain assurance that human sense impressions conform to what is “actually out there” any more reliably than a bat’s. In the face of this skepticism Blanc claims that reality is what the artist says it is. This view of the human inability to trust perception as a guide to reality can be traced back to the ancient Greek skeptics, but was revived in its early Modern form by Rene Descartes and John Locke.

Of course the question then and now remains: what would assure an artist that what they depict is actually a representation of what is “actually out there,” and not, as the Impressionists suggest, a simple notation of light mediated by the human optic nerve? Then as now, the only way to justify a truly representational form of painting is to believe that human beings possess a privileged, super-natural window onto reality shared by no other creature. And it is this meta-physical, sometimes quasi-religious attitude that would drive the reactions to Impressionism on display in this exhibition.

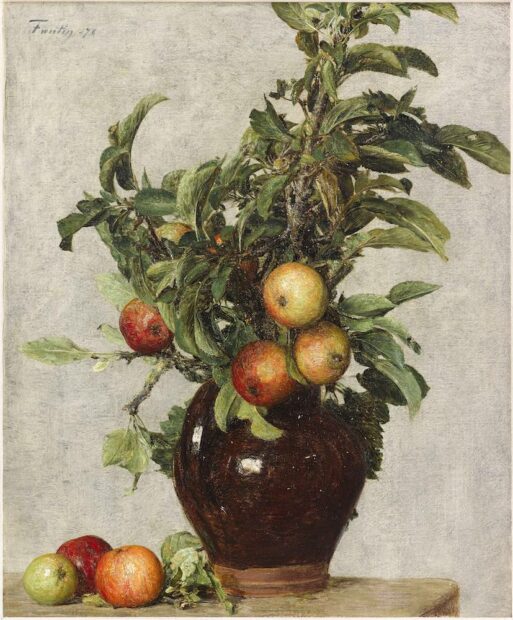

Henri Fantin-Latour, Still Life with Apples, 1878, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © RMN- Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

The two painters in the first section of the exhibition, titled “From Realism to Impressionism,” who retain most clearly a relatively untroubled trust in the conformity of perception to reality are Honore Daumier and Henri Fantin-Latour. Daumier’s interests are always more political than metaphysical. And even though Fantin-Latour was intimate with a larger circle of Impressionist and Post-Impressionists, he retains a Catholic solemnity, and the materiality of his paint application is always in the service of psychological, even reverent drama. The materiality of his paint never becomes the subject matter of his pictures.

With Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley, and others, the viewer is forced to look through the paint to see the image. Even if the atmospheric effect of French sunlight or sparkling water in these painters often verges on foregrounding joy or lightness of being as subject matter, the brushstrokes and daubs retain primacy over and above even their supposed function as representations of sensations of light. Functioning as a material obstruction to representation, the paint for these painters is more real than the image depicted just as the senses for the Enlightenment physicist are more real than the experience formed by them. The early Impressionists were nevertheless still in some sense representational painters. The conceit that they were representing optical sense impressions rather than the reality that those senses helped form still retained the idea that there was something real to represent.

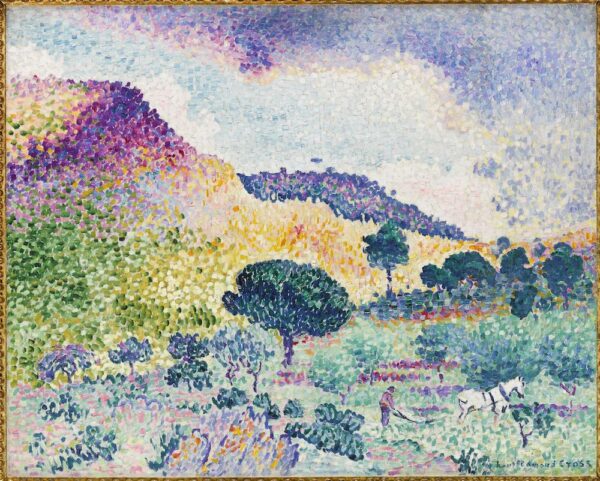

Henri-Edmond Cross, The Maures Mountain Chain, Provence, 1906–07, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

By 1900, the idea of reality being composed entirely of tiny, singular impressions of light projected against the blank screen of the mind by nerve endings had resulted in the irritatingly didactic work of painters like Henri-Edmond Cross and others who followed Georges Seurat along what must have seemed like an exciting path into the hyper-technical proficiency of Pointillism and Divisionism. As clever as the best of these canvases are, the fact that they lack the symbolism and drama that sometimes crept even into the best work of the Impressionists caused them finally to stall in a formally banal dead-end. To one degree or another, painters who rode the wave of Impressionist fervor ended their careers employing the rough, broken strokes and vibrant colors of the Impressionist palette to more symbolic, even emotional ends.

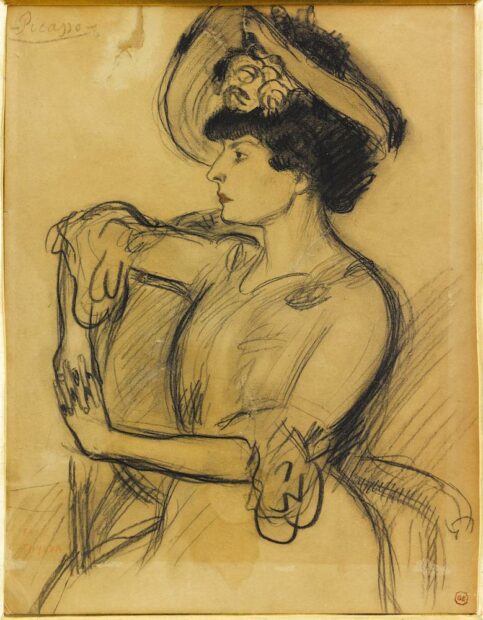

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Jane Thylda, 1905, crayon on paper, Bemberg Collection. © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

Within the first decade of the 19th century, many painters had tired of Impressionism strictly defined and began to use the formal remains of traditional painting, first deconstructed by the Impressionists — not necessarily to represent sense impressions of the natural world but to depict what was, for them, a turbulent, emotionally unbalanced inner life. If pure color laid side by side, stroke on stroke, was intended by the Impressionists and Pointillists to blend somewhere in the mechanical interaction between the viewer’s eye and brain, it was still, theoretically meant to provide if not an image of true reality, at least a human image of reality. The Symbolists, along with the Nabis (Hebrew for “prophets”) and Fauves (“wild beasts”), comprised a new generation of artists who used pure color and unblended, broken brushstrokes to create a hallucinatory vision of youthful inner passion and spiritual turmoil.

In 1886, Jean Moreas, a poet, published the Symbolist Manifesto. In it he writes:

“…Thus, in this art movement, representations of nature, human activities and all real life events don’t stand on their own; they are rather veiled reflections of the senses pointing to archetypal meanings through their esoteric connections… .”

The material reality, which the Impressionists idolized, became for the Symbolists, a “veil” over a truer reality that was esoteric and archetypal. In many ways, Symbolism reclaimed a classically Medieval point of view in which the worlds of material reality, myth, and religion have no clear boundaries.

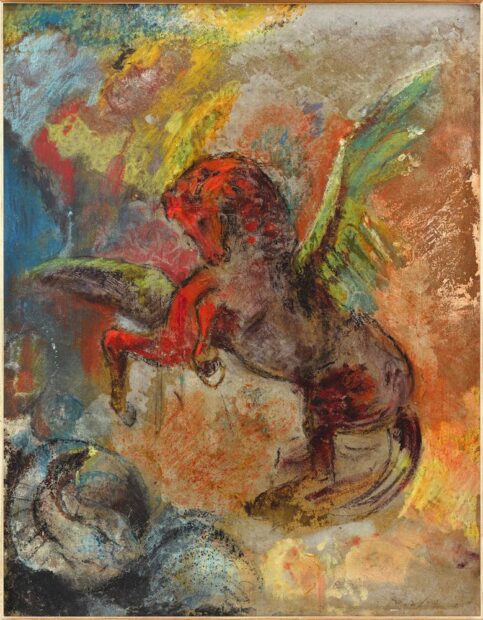

Odilon Redon, Pegasus and the Hydra, c. 1907, oil on panel, Bemberg Collection. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

Exemplified in the Bemberg Collection by Odilon Redon, the Symbolists revived and reinvigorated ancient Greek and Roman stories of human struggle within supernatural reality while employing the technical realignments in the formal language of painting brought on by the Impressionist revolution. Redon’s Pegasus and the Hydra swims around in Monet’s late palette, while the hazy, thin blue oil paint in his The Abduction of Ganymede exists not as a representation of an optical impression or for its own material sake but as an invocation of the cold, thin heights of Mount Olympus to which Zeus in the form of an eagle spirits away the most beautiful mortal on Earth. Symbolism, in both its literary and visual forms, is reactionary, counter-revolutionary art at its best. Formally, it could not have existed in any historical period other than its own, but it firmly rejects the stark division between the past and the present that liberal Modernism constantly draws and redraws with each new cultural and moral revolution.

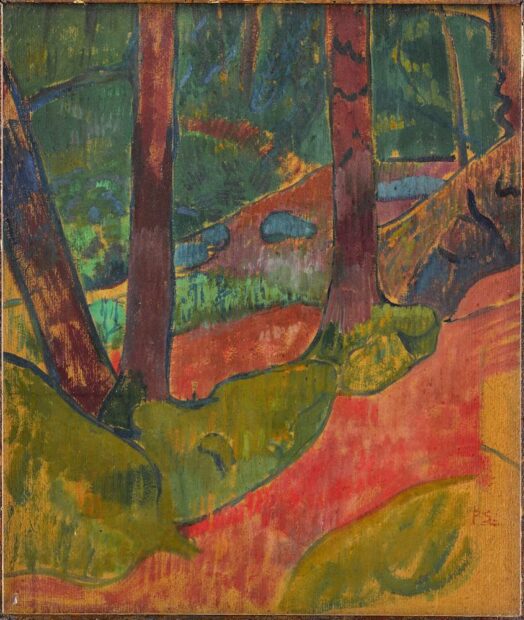

Paul Sérusier, The Bois d’Amour, 1890, oil on cardboard, Bemberg Collection. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

More firmly Modern than the Symbolists, The Nabis, typified by Paul Gaugin, often reflected the larger colonial projects of the late 19th century by seeking out still-existing examples of an idealized primitive past both within France and abroad that, at least as they envisioned it, had never really existed. Like their Hebrew namesakes, many of the Nabis consciously (sometimes half-ironically) evoked the figure of the lone wanderer surveying the desolation of the Modern world while longing for an ancient past and an eschatological future.

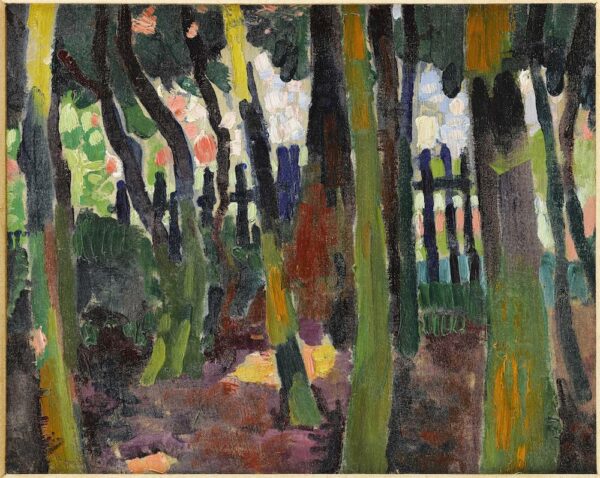

André Derain, The Clearing, c. 1906, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

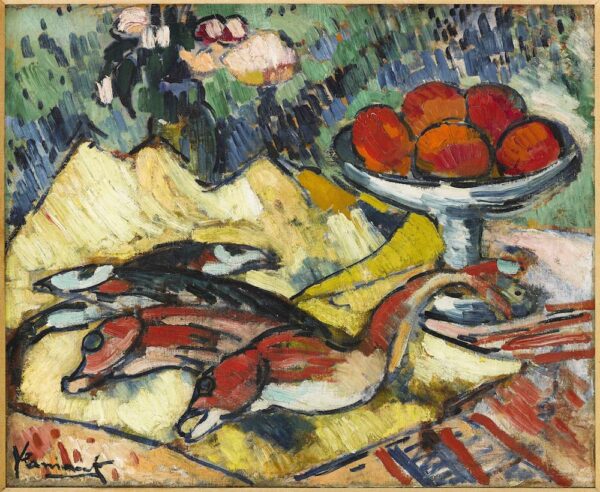

Maurice de Vlaminck, Still Life with Fish, 1907, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

Differing from the Nabis in a more explicit embrace of irony and a suspicion of idealization, the Fauves, as their name suggests, are more formally unrestrained, even anarchic, in their paint application and adherence to recognizable form. Led by the young Henri Matisse, Andre Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, Fauvism is full of drama, turbulence and explicit sexuality. If painting had in the ancient past been subject to myth and religion, and in the early Modern period put in the service of scientistic theory, it was, for the Fauves, servant to no one but the individual passions of the artists themselves. Fauvism can reasonably be understood as the last gasp of the revolutionary fervor ignited by the Impressionists, and a foreboding of the unrestrained Modern human passion that would find its consummation just a few years later in the murderous technical efficiency of the First World War.

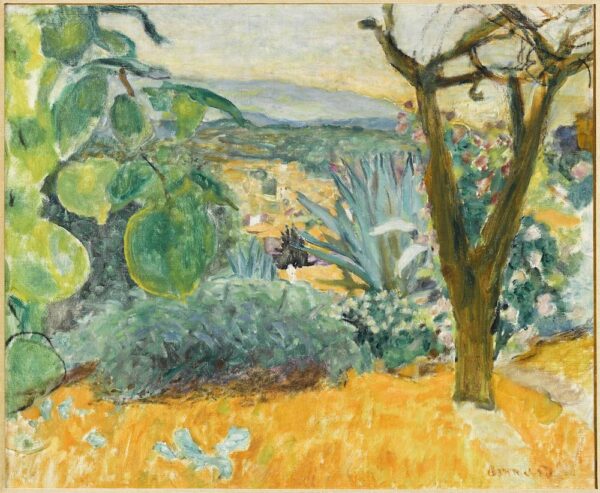

Pierre Bonnard, Seascape, c. 1910, oil on canvas, Bemberg Collection. © RMN-Grand Palais / Mathieu Rabeau

Revolutions are unwieldy things. What began as a rationalist, late-Enlightenment project of understanding painting solely in materialist terms ended in a movement that paralleled developments outside of the world of art in which technical material theory was put in the service of unrestrained human passion. The rest is history.

‘Monet to Matisse: Impressionism to Modernism from the Bemberg Foundation’ is on view at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through Sept. 19, 2021.

1 comment

Once again Mr. Bise, a wonderful read and a firm grasp you have on the relevance and response to artists in their times. Keep up the great work my friend.