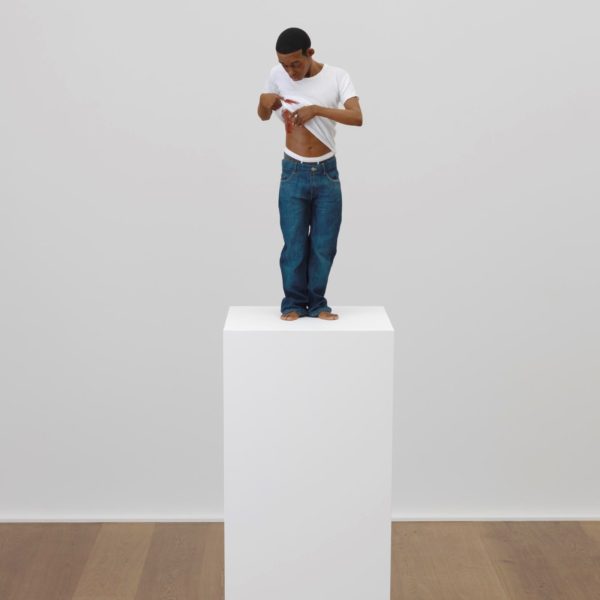

Given Ron Mueck’s career in film, it’s natural that his sculptures take on the effect of props in some larger drama, some absent set. Mueck’s sculptures have the language of filmmaking embedded in them. Having spent his early career in the movie prop, special-effects and animation business, working on Jim Henson movies, among others, Mueck takes the time-based narrative of moving pictures and re-condenses it into the frozen narrative of traditional sculpture. These sculptures act like still frames in a larger story that stars, finally, all of the people milling about them in the exhibtion that recently opened at the MFAH.

After watching most of a documentary on Mueck’s process in the lobby, I came away with the sense that through his meticulous process he casts a spell over his sculpted people, freezing them in time. He builds them and sculpts them carefully by hand in clay. It’s a traditional form of art-making, part of an unbroken tradition that may be as old as 35,000 years, through which humans have come to understand what we look like and who we are.

The viewer, as always, is tasked with the responsibility of bringing these figures to the edge of release from their freeze-framed enchantment by envisioning what came just before they were hypnotized and what might happen an instant after they wake up. This technique of freezing action accompanied by re-animation through the viewer’s imagination reached an early high point with the Hellenistic Greeks, when the mimetic power of the artist essentially freed him from what amounted to anonymous slavery. Since then it has survived as an infinitely malleable way for artists to re-imagine what it means to be human in their own time.

For Mueck, people are often lonely, imperfect, and almost always dignified in their resignation. Even when they’re paired up, they seem to be alone together. Two teenagers stop, their arms around each other. The girl’s palm presses against her outer thigh in a nervous gesture that will be broken seconds later. The boy seems to be consoling her, his lanky arm awkward in the pocket of his cargo shorts because he doesn’t know what else to do with it.. Will the two stand there a while longer or will the boy, whose right sneakered foot seems ready to pull him out of his frozen moment, gently pull the sad girl toward him and pass us by?

An old woman sits down to rest, fatigue visible on her face, her mouth open, heavy with breathing. Her calves, exposed through tan nylons like the kind my mom used to bring home in plastic eggs, are swollen from standing or ill health or both. Her blood-shot eyes stand out against her pallid skin. I’ve seen this drained color and waterlogged fatigue over and over again in my hospital adventures. Untitled (Seated Woman) is a picture of a human being coming to the end of her life, not today, maybe not tomorrow—but very soon.

Mueck’s sense of people as mostly isolated is most powerful and shocking in Mother and Child. An exhausted woman lifts her disheveled head to look into the wrinkled, alien face of her newborn, crouching on her deflated stomach. There’s a real vacancy in her eyes as she stares at this living creature still attached to an umbilical cord that snakes its way under the child’s body and into the red, swollen doorway to the just-vacated womb. As physically visceral as some of his representations are, Mueck’s people are unnatural, pushed into the territory of the uncanny.They’re often described as hyper-real. But in relation to someone like Duane Hanson, with whom he shares some similarities, he’s Hieronymous Bosch. Where Hanson’s sculptures are rendered with a neutral, exacting realism that leaves his subjects’ inner worlds unrevealed, Mueck’s people ooze angst and drama.

Mueck sees everything through his childhood psyche. This is most obvious in the fact that many of his earlier people look a lot like him (though later works do move away from this and lose something in the bargain). The artist’s characteristic long nose and prominent chin finds their way into many of his faces, including his self-portrait, which, when you circle around reveals itself to be a mask. This is good old-fashioned 19th- and early 20th-century psychology. I really wish it would come back into fashion. I like Mueck because he seems like a compassionate self-sacrificing narcissist. It’s always a relief to see an artist wallowing publicly in the muck of his own psychological stew. It makes me feel less lonely.

Artists who pay close psychological attention to the world around them usually pay that kind of attention to themselves first. The individual starts to identify with strangers, like the grocery-laden mother in Doc Martens with an infant slung under her coat in Woman with Shopping. Mueck saw her emerging from the London underground and quickly sketched her on a scrap of paper. The sculpture that results from this captured moment is a fusion of Mueck himself, all the women he has ever cared for, and the person he imagined the woman to be. In the end, I see most of the work in this exhibition as some version of Mueck himself. Autobiography seems to be the engine that keeps Mueck’s world running.

His epic-scale works, like the elderly couple on the beach in Couple Under an Umbrella and the massive, beached newborn in A Girl that closes out the exhibition, function very differently than the smaller-than life-size objects. They’re no less masterfully crafted but what was the intimate voyeuristic experience of peeking through mental dollhouse windows onto the domestic conflict between Mueck’s id, ego and super-ego, becomes a spectacular experience where contemplation is exploded into confrontation. Smaller works demand a different kind of attention. Increasing not just the size of a work, but the scale of representation within it (whether drawing, painting, or sculpture), is always a difficult proposition.

The enormous, bloodstained newborn in A Girl is undeniably powerful. It’s a great work of art and I accept it and understand the importance of it as an idol to a secular world free from gods. If once upon a time only deities or the kings and queens who embodied them on earth would be afforded such representational real estate, Mueck’s massive baby expresses the truth that our own human nature is the only god with which we have to contend with these days. But A Girl also overwhelms me, asserts its dominance over me and betrays the intimate collaboration I have with the smaller works. For me Mueck’s smaller sculptures have a magnetism that becomes diluted in the larger works.

The tension between size and scale seems ideally balanced in Man in a Boat. A pale, middle-aged man, who I imagine to be a conflation of the artist and his father, is ferried across a mythological underworld river. The boat he sits in is life-size; in fact it’s an actual boat. The scale of the canoe butts up against the smaller figure making him seem even more shrunken and lost. And where’s the ferryman? It’s a stark, bleak and yes, melodramatic work that evokes cinematic horror and ancient mythology at once.

As I left the exhibition I exited through the museum’s collection of Hellenistic bronzes, and as I stopped to look at a 2nd-century BCE head of Alexander the Great as Poseidon, it seemed that the difference between how those people saw themselves then in that powerful ancient figure, and the way we’re able to see ourselves now in the fragile humanity of Mueck’s men and women could not be more vast.

Through Aug. 13, 2017 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

2 comments

This exhibit makes me think Mueck is an existential version of Jeff Koons. But we all secretly know they are just ripping off Magritte.

P.S. Crystal Bridges has a nice Mueck piece in their collection. Alice Walton I’m available for consultation!

Mueck is divinely talented. Will he exhibit here again?