We are in the age where any contemporary group show at a gallery or museum will consider and most likely seek work by an array of people who engage in “social practice,” meaning the work is about the world we live in (and often its many horrors). The impetus for this is self-evident: a rectification for centuries of white, patriarchal, colonial art that set a very narrow frame; and also, a philosophy that art that is wholly aesthetic and depoliticized is a privilege of an out-of-touch, mainly white and male ruling class. The benefits of diversity in art are obvious — it is more interesting, more vital, and above all more just to have an egalitarian range of voices.

Social Practice is a bit more complex, for me at least. I hold a bit of a (small c) conservative position that art is, on some level, intrinsically impractical and that the creative instinct should not be over-concerned with producing something that will edify and better those who view it, but instead seeks the ineffable thunderbolt of resonance and connection. These philosophies can of course coexist and are not exclusive of each other.

The risk of social practice is the possibility of swinging into didacticism, where you begin to feel that you’re not at an art exhibition but rather at a history museum. All this is why Blue Star’s current group show, The Sitter, is so dazzling, bracing, and downright uplifting. Echoing an adage by Martin Scorsese, “The most personal is the most creative,” The Sitter provides space for several artists to not simply tell their stories, but to spin a whole intricate and lush world.

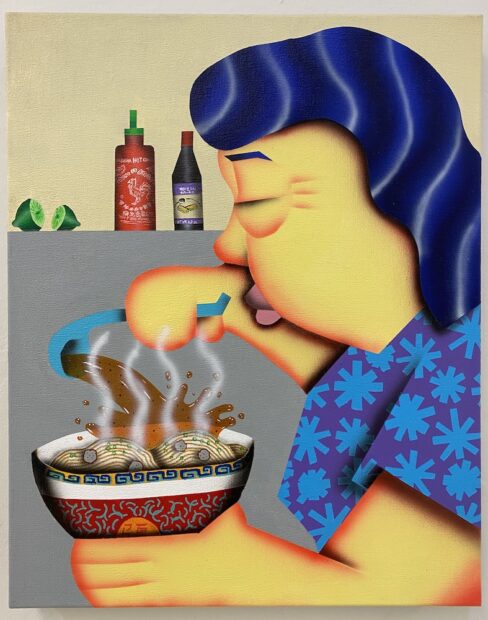

The show is particularly good at taking stereotypical tropes and visuals and not simply neutralizing them of their negative energy, but reclaiming them as aesthetic tools in a humanist project. Take Loc Huynh’s acrylic works of his family. Huynh uses yellow tones and exaggerated, porcine features, directly confronting centuries-long caricatures of Asians and flipping the polarity with the force and resolve of an electromagnet. Mom Making Pho is a symphony in miniature — you can almost smell the fragrant broth splashing in the bowl, and a piquant flood of nostalgia fills the frame regardless of where one’s mother is from and what dish she makes.

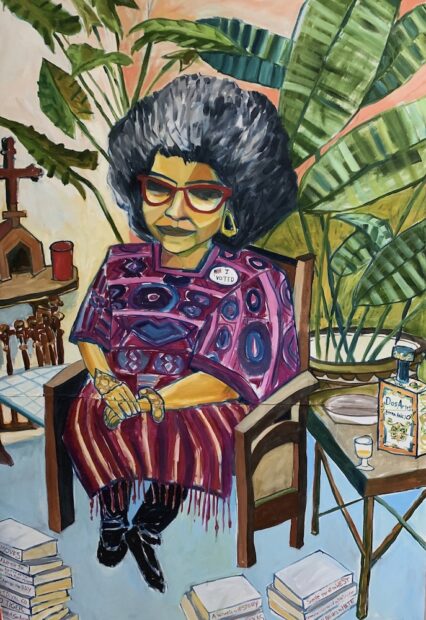

Cruz Ortiz is such an iconic artist in south Texas that it’s easy to take him for granted and let his vital work recede into a kind of verdant cultural foliage. The works in The Sitter find Ortiz utilizing the tropical (and historically colonial) palettes of Gaugin and Matisse to lionize such subjects as Professor Emeritus of Bilingual Studies, Ellen Riojas Clark. Clark is resplendent in a patterned dress (with an added I Voted sticker), surrounded by books, with a shot of añejo tequila to sip through the afternoon. The message is simple: kings and queens are all around us.

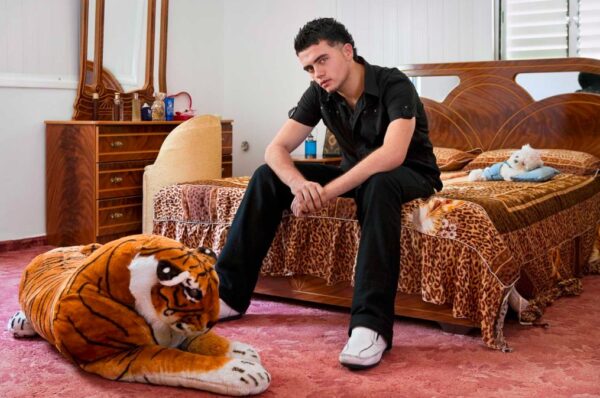

Sometimes good intentions in depicting marginalized and/or stereotyped communities can lead to mawkish or tone-deaf work that revels in poverty or condescendingly seems to say: “These people are just like us.” Israeli photographer Natan Dvir does the exact opposite with his staggering and beguiling portraits of Palestinians. Divr’s subjects are shot in their bedroom, boxing gym, or other highly personal spaces. The wall text for each piece is the subject’s own words describing a snippet of their lives, just enough to give you a glimpse of their world, their dreams, their histories — these pathways beam like shafts of light through stained glass, and harmonize with the photographs to form a portal into another soul.

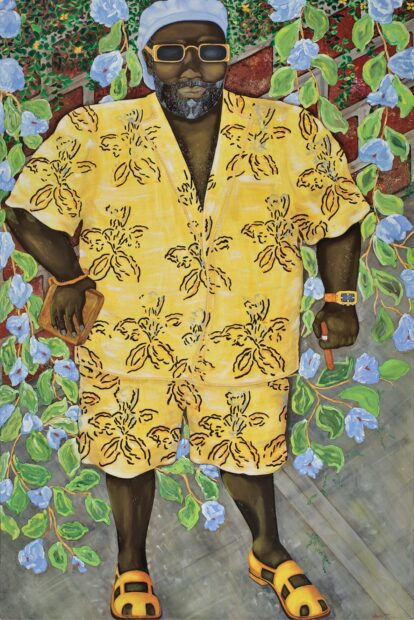

The highlight and revelation of The Sitter are the paintings of San Antonio artist Carmen Cartiness Johnson. Johnson’s acrylic works pop like a more upbeat hybrid of Kerry James Marshall and David Hockney’s California works. Johnson’s pieces have all of the embossed dimensionality — her subjects appear ready to walk out of their frames and into the world — but have a warmer, more empathetic hue than the cooler-dispositioned eye of Marshall and Hockney. The Octagon Room is a four paneled tour-de-force successfully positioned from a seeming impossible perspective — a sort of roving God’s eye — of what appears to be a gathering in a house that is also a bar and a music club. The edges of the work begin to bow and fold back on themselves, and create a succinct treatise on the fourth-dimensional geometry of life — how each new place is just another stretch of arc in the sphere of one’s environment.

Johnson’s Men in Short Sets Series, Big Man is perhaps my favorite piece in the whole show, a magnificent and deceptively simple portrait that unfurls itself in a leisurely splendor. A “big and tall”- sized middle-aged man in a tropical yellow short set holds a cigar and a wallet. He wears sandals, sunglasses, and a Kangol hat, and stands in front of flowers with a tiny, wry, elusive smile. It is simultaneously the coolest fit I’ve ever seen, and a deeply soothing, reassuring work that speaks to the worth and power of dignity and freedom. Big Man perfectly summarizes the tone and mission of The Sitter: the quest to be oneself, to sit easy with oneself. May we all find our short sets and wear them with such casual grace.

Through Sept. 5 at Blue Star Contemporary, San Antonio.