I met Christie Blizard earlier this year in San Antonio, during my ArtPace/Glasstire residency. Mutual friend Libby Rowe introduced us and told me I would love Blizard’s work — that it was edgy and weird in the best possible way. She was correct, though it was a vast understatement.

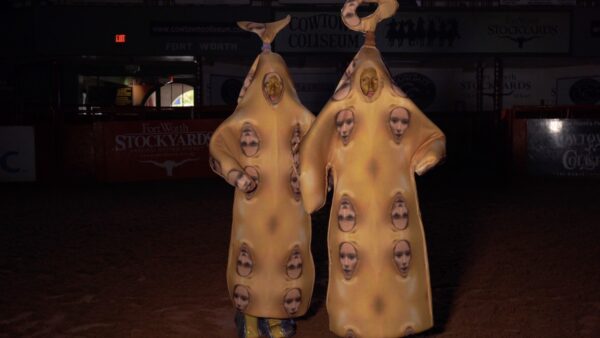

I immediately connected Blizard’s post-human/sub-human alien characters — non-binary alter egos that defy description. For their 2017 ArtPace exhibition, Blizard transformed a 2003 Pontiac Grand Am into a Back to the Future-style vehicle with winged doors, and commissioned a puppeteer to create a puppet based on French theorist/philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, who believed in the potential of artists to develop new ways of thinking that deconstruct existing hegemonic structures. Blizard created a series of performances for the exhibition featuring them wearing alien-like costumes that included 3D printed masks of Elle Fanning, Scarlett Johansson and Jennifer Lawrence. The work addresses the apathetic and complacent state of current mainstream American culture, and challenges viewers to question their role in maintaining the existing social order, while the artist and puppet try to have a thought outside their bodies.

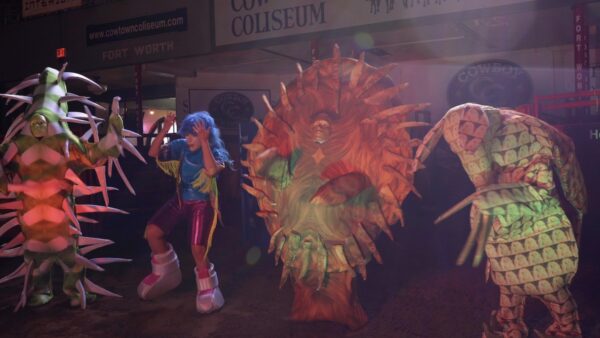

For the past one and half years, Blizard has been working on an alien opera, Let My Body Eat the Sun, which was to open at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts (FWCA) at TCU on March 12. Unfortunately, the gallery is closed due to the pandemic, but there are virtual opportunities to experience the work. FWCA’s Curator Sarah-Jayne Parsons saw Blizard’s video from their Artpace residency, and commissioned Blizard to make a work for the 100-year anniversary when famed opera star Enrico Caruso sang at the Cowtown Coliseum in Fort Worth. Blizard not only composed the opera, but also directed and helped to film, along with Lynné Bowman Cravens, Chris Wicker, and Justin Ferrell. Blizard also edited the video, and designed and made the costumes.

Colette Copeland: In the online video chat with Sara-Jayne Parsons last fall, you discussed your opera as a Greek tragedy with two singers/narrators and a main character based in Texas, who crosses over to death and comes back as a spirit. Three other characters — a cactus, a tumbleweed and an armadillo — assist the hero in preparing for death. I’m interested in the metamorphosis of the animal and plant Texas icons into operatic characters. I think of the properties of a cactus: resilience under harsh conditions, spiny armor to protect itself, and a provider of sustenance to animals and humans. The tumbleweed is also tough, surviving desolate conditions, but a traveler that spreads its seeds and reproduces wherever it goes. I read that the armadillo can be a spirit, totem, and power animal that can assist one in digging for the truth or helping someone who is lost find their way, or help someone establish boundaries. Tell us more about the development of your characters and their roles in the quest.

Christie Blizard: Those are interesting observations about the characters and animal creatures. I wanted the animals and plants to represent the Texas landscape, particularly west Texas, where I lived for six years. I am interested in the emptiness, vastness, and deep skies of that area. I wanted to focus on the paradox of openness and claustrophobia that I felt when I lived there, with a desolate loneliness but with an ability to tune your mind like a radio because of the silence.

I wanted the characters to feel mythical and other-worldly, so the performers wore masks to hide their body and identity. Most of my characters are ambiguous and also resemble insects, so I am interested in one’s difficulty to pinpoint where exactly they are, what time they are, and what they represent. They also look a little bit like mascots when in an arena. These specific characters came to me immediately, and then Sara-Jayne brought the idea of the opera to me, along with the abstract story of passing through the death dimension, which is what happens to the main character.

These ideas were all there from the beginning of the piece. The characters evolved mainly because of the performer inside the costume, and this was my first time directing a big piece, so it was most interesting to watch how the performers interpreted the characters. This was the most collaborative piece I’ve ever done. The singers were Bronwyn White and Antonia Valdez. The performers were Adrianna Touch, Adelynn Young, Kim Phan Nguyen, Ashley Stecenko, Jazmin Gonzalez and Lynné Bowman Cravens. They all did an amazing job.

CC: The coliseum as the backdrop for an opera is an interesting cultural paradox. Cowtown Coliseum has a history of rodeo performance. In thinking about rodeo as a metaphor for taming the wild and historically a site for machismo performance, I wonder how you incorporated the history of the site into the contemporary storyline? Does this cultural collision manifest in the opera?

CB: That is a very interesting question. I knew that I didn’t want to make an opera about a rodeo because I do not know much about rodeos and would feel like an imposter making something that I don’t experience on a regular basis. I was more interested in the Dada impulse for the absurd and the irrational, although I like that there are metaphors that arise from the rodeo space, and I appreciate your insights to that. Part of my original idea to link the work with Enrico Caruso’s performance was to tie the opera into the rift space of the rodeo clown, as one of Caruso’s leading roles was a clown in the opera Pagliacci. However, I also didn’t want to make a piece directly in response to Caruso’s performance. I was more interested in the high drama of the opera combined with the irrationality of Dada’s legacy in response to the savagery in the world.

With regards to the machismo aspect of the rodeo — in all my work, I am interested in the non-binary as I have come out as non-binary, so I try to make my work inherently not polarized towards a gender or a reaction to it, but for it to stand outside of gender or ideally, all binaries.

CC: Let’s talk about your music and how you approach composing a contemporary opera. Your experimental music contains a lot of synthesized sound, including compositing many layers of distorted ambient and archival sounds recorded from various sources. How did the opera evolve?

CB: I worked for many months on the audio, recording myself playing various analog synthesizers to find sounds that resembled vocalizations with an emotional tenor to them. Much of what I produced was atonal, which I felt was interesting and not very common in operas. I would then collage these sounds together until I found the scenes and abstract narrative emerge from them. Since I do not write music, I had to find a different way to communicate the work to the singers, so I sent them sound clips in the order of the composition, so they could transcribe them for vocalization. The singers did a great job of interpreting the sounds I gave them. There is also Brahm’s Lullaby and the O Canada in the opera.

CC: Your artist statement mentions some life-altering experiences from 2015, that not only changed your artistic practice, but your relationship to the world. In the chat with Sara-Jayne Parsons, you spoke about the costuming/characters that you create as a means for the dead to communicate to the living, which I interpret as a medium of sorts. Parsons mentioned that this must be a great responsibility, while you responded that it was an honor. I wondered if you channeled Enrico Caruso, and if so, was he responsive to the experience?

On a broader level, based on your experiences, what can we learn from the spirit world not only about death, but about life?

CB: I do not really consider myself a clairvoyant or to be able to channel any particular person directly. I have had ecstatic experiences and lucid dreams that I feel have given me insight beyond the death dimension. I have become recently interested in the visionary Saint Hildegard Von Bingen and her prophesies. The illuminated drawings of them are quite amazing. Because my work with sound is primarily through analog instruments and their electrical currents, I use that as a means to tune into different frequencies, to find a ghost in the machine. To me, these frequencies open up new types of spaces that I can enter, and I find they seem to trigger something that seems ancient and beyond the binary of life and death. From these experiences, what I have learned is that I believe we receive help when we pass into death, and that there are frequencies that can connect us to a vastly different otherness. If we can tune into these frequencies, we can learn to explore them.

****

“Let My Body Eat the Sun” by Christie Blizard, Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, TCU, March 12-May 1, 2021. You can watch the video here.