Raul Rodriguez, Sara Cardona, Fabiola Valenzuela, Melissa Gamez-Herrera, and Jessika Guillen at FWCAC on April 20

Aqui/Ahora is one of the ten exhibitions currently on view at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center. This one — a group show — and another, Chesley Antoinette’s Tignon, feature works by artists of color who explore themes that connect with cultural identity and the politics of capitalism, immigration, and brown bodies in America. The sprawling art center is in the building that was the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth until 2002.

Aqui/Ahora was organized by Latino Hustle, the self-described curatorial collective which aims to “create space for Latino/X artists, musicians, and creators across the Dallas/Fort Worth Region through exhibitions and cultural programs.”

The group show includes works by Texas-based artists Francisco Josue Alvarado Araujo, Sara Cardona, Melissa Gamez-Herrera, Jeffry Valadez, Giovanni Valderas and Fabiola Valenzuela.

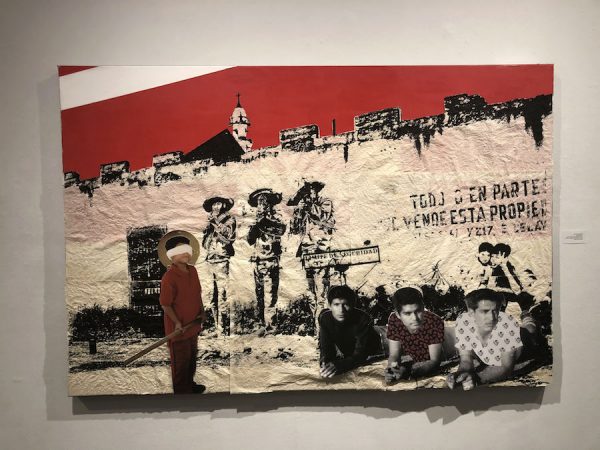

Valadez’s Limite de Seguridad loosely translates to ‘Fail Safe’ and is one of a few collages exhibited in Aqui. The work is a mix of silk-screen on paper, oil on canvas and collaged photographs. A blindfolded kid with a gilded halo, dressed in red, holds a stick as if about to strike a piñata. Behind him are three armed men in hats with ammo belts crisscrossed over their torsos; they’re either part of a firing squad with a blindfolded victim, or they’re protecting the innocent from the viewer.

In the 1964 Sidney Lumet movie Fail Safe (an unavoidable comparison given the loose translation), US nuclear-armed bombers cross into Soviet Russian territory and bomb Moscow, because they’ve crossed the fail-safe point and can’t be recalled. To prevent an all-out nuclear war, the Russians are given permission by the US to bomb New York City. The tense scenario in Valadez’s Limite plays out in front of a wall, and it’s hard to ignore the symbolism given US southern-border politics in 2019. At the bottom of the collage are three male figures, lying on the ground, propped up on their elbow and looking pensive. We are Sam Jackson’s Jules Winnfield from Pulp Fiction, trying to figure out our role in this allegory. Are we the tyranny of evil men, or the ones who shepherd the weak through the valley?

Another collaged work in the show with a cinematic evocation is Cardona’s Gone with the Wind. It depicts multi-colored serape blankets with two tires contorted and flailing within their frame, as if wind swept across a six-foot swath of gallery wall. This work is no doubt informed by Cardona’s affinity for the analog process of film editing and assemblage that’s typical of her practice. The blankets juxtaposed with tires conjure historical and contemporary visions: it’s easy to imagine marketplaces, low-riders, and the history of woven fabrics. Gone with the Wind’s title also implies a connection to the movie of the same name, which of course presents a heroic and romantic retelling of the brutal legacy and reality of slavery and subjugation in 1800s America.

In a nearby gallery, Chesley Antoinette’s Tignon explores how Creole women in 18th-century New Orleans employed creativity and invention to circumvent the Tignon law which required them to wear head coverings meant to suppress their features while in public. The head wraps are colorful and personalized adornments that revived centuries-old African traditions, and they thwarted one aspect of subjugation via colonialism. The exhibition contains dozens of head wraps created by Antoinette, some of which were used in photographic reenactments of historical images of women wearing Tignon. In fact, the show reads like a historical document, which Antoinette brings to life through workshops that allow participants to share in this empowering ritual in the same way Antoinette visualizes empowered women of that era doing so.

Back to Aqui/Ahora: Latino Hustle convened a panel to discuss the show last Saturday, moderated by co-curator Raul Rodriguez. The conversation delved into some of the expected issues around a Latinx show organized by a group called Latino Hustle. Namely, how do artists navigate the Latin-ness of their identities while staying true to their identity as artists, and is it possible to exist as an artist outside of culture and politics? We all, of course, exist in a sphere of politics and culture, but confronting the expectations and issues that artists of color face in their practice is an especially dogged experience — the burden of which seems to fall only on historically marginalized sections of our society. Aqui/Ahora poses some important questions about how artists of color assert themselves in this socio-political context, one that on the one hand encourages them to choose between culture, politics, and art, and on the other hand convinces them that that choice is a futile one.

Cardona was keen to respond to this issue, saying “I do see empowerment in what we do, but I often feel the frustration of carrying the burden of being the ones that are in response mode. I know it’s a fact of circumstance, but as artists of color it seems like a double responsibility to make your work and to continually respond to racism — it’s exhausting to be always responding to the ills of the status quo. We need to gain more power as producers, educators, curators, etcetera, within the infrastructure of the art universe.”

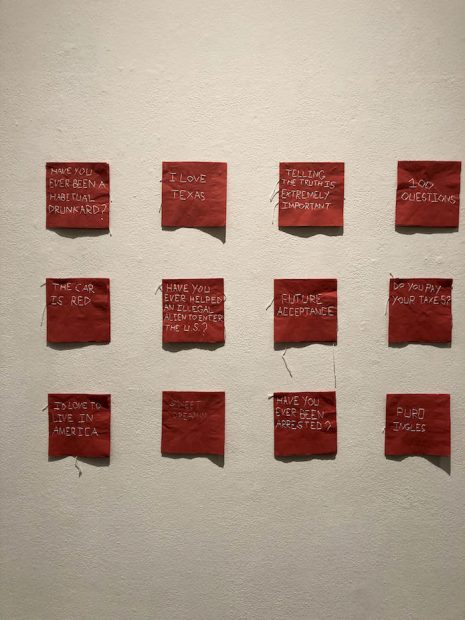

Valenzuela’s approach is to bring a personal approach to her work. “I feel a responsibility to be honest, and to show what I know. It’s all about honesty in the work,” she said. Among her works in Aqui/Ahora is a series of red napkins embroidered, in white thread, with questions and answers from the citizenship tests administered to her parents decades ago. There were also cakes at the opening reception that were printed with some of the questions and answers, as well as the presidential welcome letters presented to naturalized citizens. Consuming the cakes suggested a kind of ritualistic association with embodying what it is to be an American. I was reminded of liturgical rituals that incorporate the ingestion of food and drink as a way of connecting with others; in this sense Valenzuela’s work became even more poignant.

Listening to the panel address, among other things, the tokenism that often accompanies showing Latinx artists in exhibitions and collections — such as programming artists only in narrow curatorial contexts around cultural holidays and cultural identity themes (read: Latino History Month, Cinco de Mayo, and shows organized by groups called Latino Hustle) — only reinforced the similarities between their experiences and those of African American, female, queer, and other hyphenated, marginalized groups and artists.

The reality is that politics, culture, and art are inextricably linked within every artist of color, and there is opportunity in that intersectionality — of which Aqui/Ahora and Tignon remind us.

‘Aqui/Ahora’ and ‘Tignon’ are on view at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center through April 26, 2019