The Texas-Mexico border has taken on multi-level heft since the election of Donald Trump. There is the racist myth spouted by Trump — and believed in slavishly by mainly older, white citizens usually living far away from any border — that the border presents an endless influx of drugs and ‘vicious’ (Trump’s favorite word) criminals. There are the horrific real consequences of such mania — Boer-War-style concentration camps for refugees who’ve tried to cross, often desperately fleeing a country from which the US contributed to its fall into chaos. And there is the day-to-day reality for some large cities and towns (El Paso, Del Rio, McCallen, Brownsville, Laredo), outside of myths, as they have been for more than one hundred years.

Carlos G. Gómez, who died in 2016, was a seminal and legendary figure in the art scene of the Rio Grande Valley. While teaching at Texas Southmost College, the University of Texas at Brownsville, and UT Rio Grande Valley, Gómez, who was born in Mexico City, mentored countless artists during his 30-year career. Gómez’s works are elegant riffs on symbols of the psyche and Mexican cultural folklore, and his skill with portraiture is striking. For Different Skin, Presa House in San Antonio exhibited the works of three Brownsville artists who studied with Gómez, as a tribute to his memory.

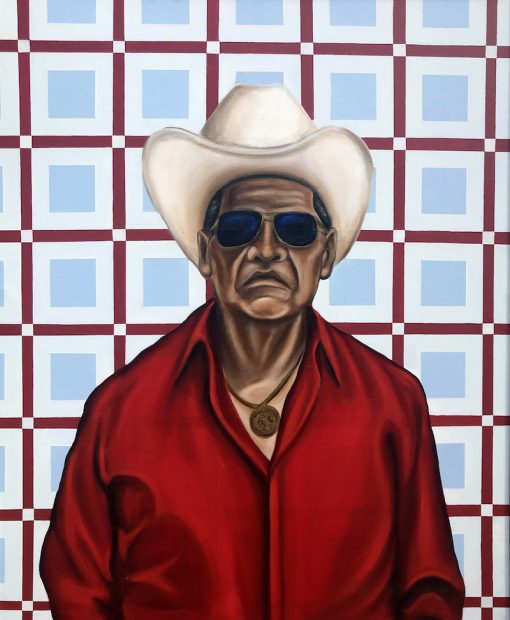

Selections from Jesse Burciaga Chingonadas series imbue portraits of day laborers and blue-collar Mexican workers with a sense of grandeur. Chingon is Mexican slang for ‘cool’, and Burciaga’s portraits with geometric, folkloric backgrounds place people often forgotten or looked down upon as icons, in league with cowboys and rock stars. Burciaga in the catalog movingly remembers Gómez:

“Professor Gómez opened my eyes artistically and introduced me and steered me toward the direction of Chicano Art. He once wisely said to me, ‘Why look at your neighbors for ideas, when your own backyard is full of tradition and culture.’ Those words have significantly influenced my work.”

This spirit of imagination and recovery reverberates through the show. Josie Del Castillo’s expansive self-portraits confront body and mental health issues with an idyllic expansiveness. One canvas, cut like a cloud, depicts Castillo with a chapel on her head, in repose in a tropical field of the Gulf of Mexico. The image is melancholic yet resolute — a moving and mysterious depiction of one’s spirit.

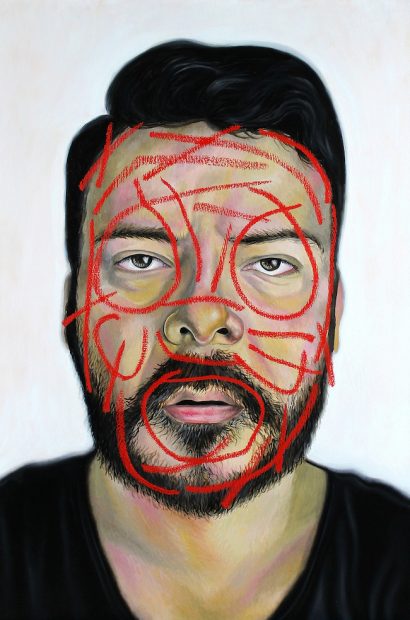

Alejandro Macias’ works are detailed and vibrant, appearing almost embossed. A self-portrait is marked by red tracks across his face, creating a map of inscrutable history, and a war paint of protection and resilience. Another piece, recalling Francis Bacon’s screaming popes, depicts a glowering padre framed by a pastel background. Macias’ works explore the faces we compose as shields and defenses, and how in spite of such façade, they are intrinsically revealing.

‘Different Skin’ took place at Presa House, San Antonio, from Nov. 2-24, 2018