Ed note: William Reaves / Sarah Foltz Fine Art in Houston is currently hosting a retrospective of Stella Sullivan’s work.

I was 17 when I met Stella Sullivan. It was 1980. A family friend of my school chum John was taking painting lessons from her, which is how I met her. I had taken lessons from a Sunday painter in Spring Branch, but she was not a very good teacher. And I thought it would be fun to paint with John, who was a far better artist than I was. Neither of us knew anything about painting — we were pen-and-ink guys who learned how to draw by looking at comic books and Mad Magazine. Paint was a mystery that we were interested in solving.

John must have recommended studying with Sullivan to me. He recently told me that he did it partly as a way we could hang out together — although we were close friends, in high school we had drifted apart somewhat due to being tracked differently — and the only class we regularly shared was art. Taking painting with Sullivan meant hanging out together for a few hours every week. I drove us to class in my enormous ’77 Chrysler New Yorker, subjecting John to my musical tastes. (He was a literal choir boy and wasn’t too fond of Bob Dylan’s singing.)

Going to class at Stella Sullivan’s took us to a neighborhood that neither of us knew. Her house at the corner of San Jacinto and Southmore in Houston was eccentric and unique, designed by her father, Maurice Joseph Sullivan, who was one of Houston’s pioneering architects. I was always fascinated by its pale pink stucco exterior. Maurice Sullivan was from Michigan and studied in Detroit before moving to Houston. Stella Sullivan went to Rice University as an undergrad and then transferred to college in Detroit before attending Cranbrook Academy just outside of Detroit. She graduated from Cranbrook in 1954 and came back to Houston.

Sullivan’s house is still there. It is surrounded by midrise apartment houses that have mostly displaced the single-family homes in the area. A suburban neighborhood this close to downtown was always going to face pressure to develop into a more densely populated neighborhood, so I can’t say why Sullivan’s house has survived. It is well-maintained and has an historical marker celebrating the contributions to Houston of Maurice Sullivan. Perhaps there should be a marker for Stella Sullivan as well.

There was a tiny out-building on the west side of the house where Sullivan taught us. She started teaching in 1961 at the Museum School (later the Glassell School). She also taught in Spring Branch Adult Education, at the University of Houston and at Sam Houston State. She later opened her own school, but later had to close it and started offering private lessons. And that’s where John and I came in — two obnoxiously self-absorbed teenagers from the suburbs, coming into what was, at the time, a semi-rough urban neighborhood — for art lessons every Monday night.

Unlike my amateur teacher in Spring Branch, Sullivan had a very precise program of instruction. Every class started with us drawing blind contour drawings of each other. John and I would face each other, never lifting the pencil off the paper or looking at the paper while we drew. It was challenging, and neither of us ever got it quite right. But it put our minds in the right place to start painting. She demanded we focus intensely on the subject matter, which was, invariably, a still life that she set up using objects from her house. She forced us to make do with a minimum of paints. We had exactly ten colors to work with. I wish I could remember them all — I remember titanium white, cadmium red, phthalo blue, burnt umber and ultramarine blue. We didn’t have black paint. If we wanted to paint black, we had to mix ultramarine and burnt umber. It still seems magical to me that you can produce black from mixing two lighter colors of paint. And not only that, but by carefully adjusting the amounts of each color, we could make the black warmer or cooler. To get our knowledge of mixing paints up to snuff, we were required to make a mixing chart of 100 squares — each one showing a 50/50 mixture of every paint we had. This was homework, and to be honest, I don’t think either John or I ever completed it.

The technique Sullivan taught was invariable. You started with a blank canvas, painted in an underpainting, and then sketched a design on top with a contrasting color. You did not drag your brush across the canvas or try to blend colors — because that would come later. In the beginning, she wanted us to just lay down the colors flat, as if we were pointillists. Our beginning technique produced work that resembled that of Maurice Prendergast (minus the artistic brilliance). The artist she showed us the most was Pieter Bruegel, whose work in no way resembled what we were doing. But Bruegel remains a favorite of mine to this day.

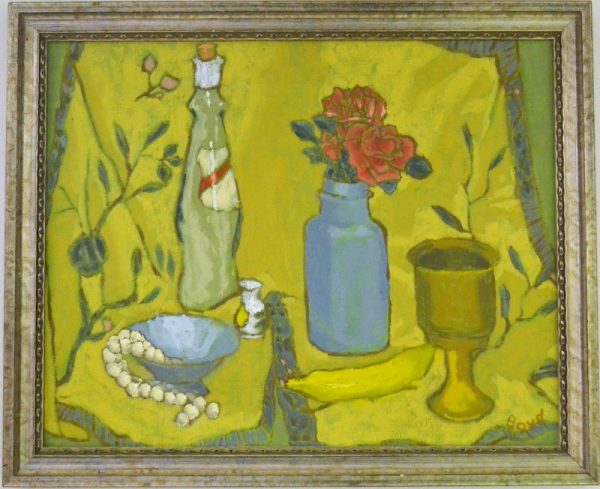

During class, Sullivan always had the radio playing classical music. About halfway through every class, we’d stop for a hot chocolate. They were some of the most enjoyable hours of my life. And while the paintings weren’t all that great, they were all right. I still feel pretty proud of Still Life #3 from 1980.

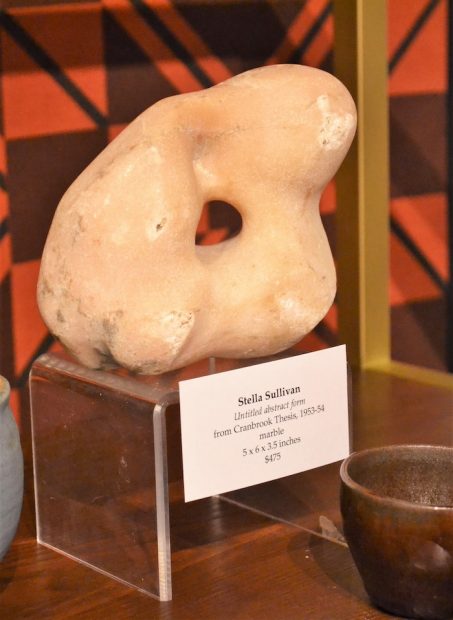

The gallery William Reaves / Sarah Foltz Fine Art in Houston is currently hosting a large retrospective of Sullivan’s art. The show includes work from her entire career, from 1949 to 2007, including a piece of carved marble that was part of her thesis project at Cranbrook.

It’s an overwhelming assemblage of artwork — mostly painting, but also some sculpture, drawing, graphics and fabric works. When Sullivan returned from Michigan, she and a group of fellow artists founded a craft store called Handmakers, in the middle of a neighborhood that later would be known as Midtown. The retrospective contains several works of this nature — fabrics and garments that Sullivan silkscreened with colorful abstract patterns. Her textiles appear quite modern. If Sullivan had not lived in Houston, so far from the centers of fashion, who knows what career she might have had? But she must have known the precariousness of trying to build an art-related business in Houston in the ’50s. But by Sullivan’s own account, as recorded in the book Houston Reflections: Art in the City, 1950s, 60s and 70s by Sally Reynolds, there was a small, tight-knit artistic community of which she was a part. “One of the nice things about the CAA [the precursor to the CAMH], [was that] all the people who wanted to went and volunteered, doing something relative to art, whether they were artists or not. Everybody knew everybody and got to be friends, you know, for life.” These friends included Henri Gadbois (who died just three days ago as I write this) and Leila McConnell. Both have work in the “Handmakers” portion of the Reaves / Foltz show, including a portrait of Sullivan by McConnell from 1955.

One pleasure at Reaves / Foltz is a series of self-portraits by Sullivan, including the earliest painting in the show, which a self portrait from 1949. These are largely naturalistic, traditional portraits. She had real skill at this kind of portrait — see in particular her Portrait of Oscar McCracken from 1957 [pictured at top].

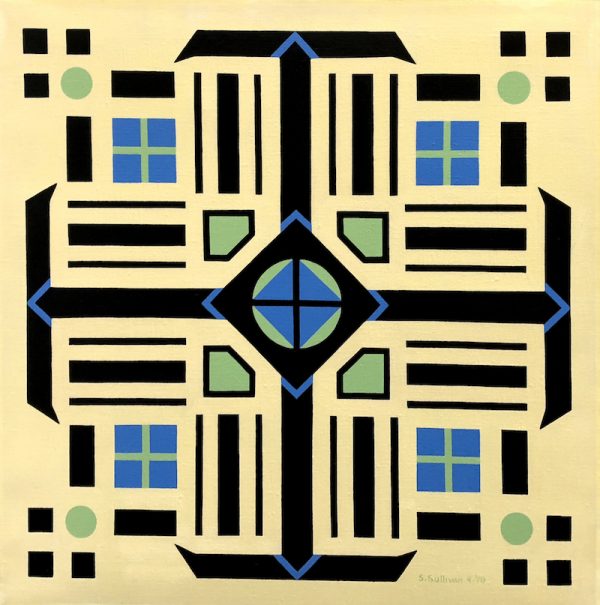

It seems to me that had Sullivan wished to make her way in the world as a traditional portrait painter, she could have. The evidence is on view in this show. But her interests as a visual artist were too broad to be corralled into one style. Sullivan was a naturalistic painter, a quasi-cubist, a geometric abstractionist, and more. When you think of stylistic variation like this from an artist, you usually find that the artist adopts one approach, keeps it for a while, and then changes. Picasso is the obvious example, and Philip Guston’s work famously took a dramatic turn in style. But this is not how Sullivan worked. She’d do a realistic painting of a house (a “house portrait,” as Sullivan called them) one day, and then a very precise and symmetrical geometric abstraction the next.

We were kids in 1980, and didn’t know from abstract art, but I was starting to discover it because I was watching the TV series The Shock of the New, which was running on PBS. Sullivan’s explanations of her own work nonetheless struck me as bizarre. Her geometric abstractions had both horizontal and vertical symmetry. Sullivan explained how difficult it was to find the exact right placement of each element, and the exact right color to provide the perfect balance in all four quarters. She sweated the details. I could believe in her effort (because that was how she had John and I paint), but I didn’t understand why. But a few years later, I encountered a description of similarly obsessive painter. In the late ’50s, Robert Irwin was working on a series of paintings which featured two parallel lines on a yellow or orange field. “I would sit there and look at the two lines, and then I’d remove one of them and move it an eighth of an inch.” (Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, Lawrence Weschler, 1982). He finished 10 of these paintings over a two-year period. “So I painted a total of twenty lines over a period of two years of very, very intense activity.” By “activity” one should read “concentration.” That was something we learned from Sullivan.

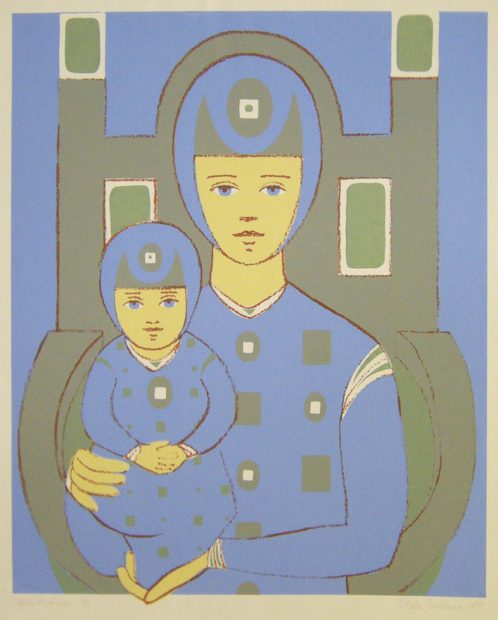

The show also displays her mastery of various printing techniques — woodcut, etching, serigraph. Some are black and white, but she loved working in brilliant color, layering large flat colors behind intricate drawings. While her paintings were sometimes naturalistic and sometimes not, her graphic works were almost always “modern” — either inspired by cubism, expressionism or abstraction. One thing the exhibition displays vividly is Sullivan’s devout Catholicism. Her work includes Symbols of the Eucharist #3, prints of Jesus, and a series of highly stylized Madonnas, including a blue and gold silkscreen Madonna and child in which the pair are dressed in what could be mistaken for Soviet-era cosmonaut costumes. Sullivan amusingly titled it Astro Madonna.

I recall seeing some of these Madonnas as a student, but it wasn’t until I saw this retrospective did it dawn on me how important Sullivan’s Catholicism was. And interestingly, all her overtly Catholic work was quite modernist. She saved her naturalism for more quotidian subject matter.

John and I graduated from high school in 1981 and went off to college. That was the last I saw of Sullivan for many years, until I met her again at a gallery event a few years ago. By then, she was quite frail, but still painting. She died at the end of 2017, at the age of 93. Her generation of pioneering Houston modernist artists is rapidly passing from a Houston that largely had no idea what to make of them.

Through Nov. 3 at William Reaves / Sarah Foltz Fine Art in Houston.

4 comments

Beautiful essay Robert. Thanks for sharing. And nice still life too!

Thanks so much for this wonderful essay about Stella Sullivan. Your still life looks a lot like many of hers, particularly in use of black outlining of the major objects and the tilted-forward perspective of the table top. Great painting!

That’s a damn decent thing to say about a crummy still-life I painted when I was 18! Thanks!

Thanks so much for bringing Stella Sullivan to our attention. A must see at William Reeves/Sarah Foltz Gallery especially considering the Deborah Colten show “Identifiably Houston – Foundations III”. We are having difficulty determining what are our artistic roots!