In 2017 it’s hard to isolate any aspect of our lives not mediated in some way by technology; it’s how we move around, how we work, and increasingly, how we interact with each other. But our close relationship with technology belies our discomfort with it. Since at least the early modern era we’ve oscillated between periods of technophilia and technophobia, haunted by Samuel Butler’s speculative prophesy of man’s domination by machines inasmuch as we celebrate their life-saving potential.

It strikes me however that most of our discussion of technology is characterized by concepts of its utility, our love for it directly related to its potential for use, and our fear to its potential to use us. The artists whose work makes up The End and the Beginning, a four-person exhibition curated by Danielle Avram and on view at Texas Women’s University’s East | West Galleries, offers a different approach to technology, imagining in it new and revolutionary potentials.

The West Gallery contains the work of Morehshin Allahyari and Jenny Vogel, two artists probably familiar to Texas arts audiences. From Iran and Germany respectively, both artists use technology to explore how memory and mythology operate on a cultural level. The East Gallery hosts collaborative work by Martin Back and Sean Miller, two North Texas-based artists more interested in technology and nature, using video and sound to meditate on natural, organic processes.

It’s a show in two parts, something the twin galleries at TWU lend themselves to: Allahyari and Vogel’s work is more emotionally dense, culturally specific, and immediately evocative — art ripe for metaphysical interpretation. While technology is more or less the “medium” all four artists work in, Back and Miller’s work is more process-oriented, visually and aurally minimalistic and if not more technologically complex, at least less overtly ideological.

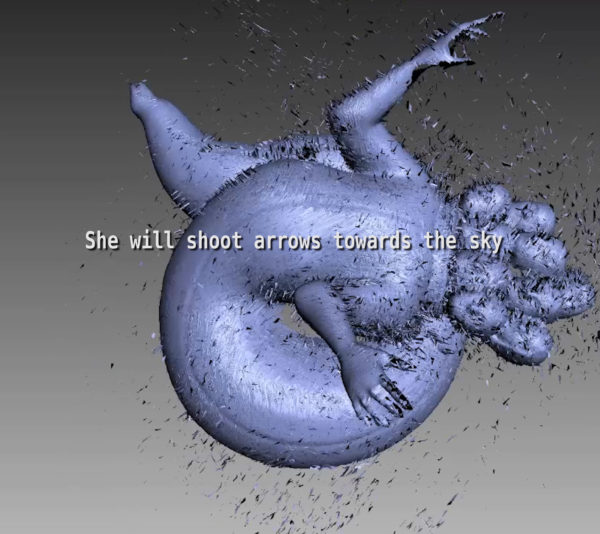

Allahyari has been exploring the positive potentials of 3D imagery and software for some time. She Who Sees the Unknown: Ya’jooj Ma’jooj is a video from an ongoing project exploring issues of colonialism and feminism through the lens of myth and the female figure. The video relates the imagined story of two ancient tribes, the Ya’jooj and Ma’jooj and their connection to a powerful female goddess through text and 3D imaging technology. Across the gallery Vogel’s 3D animation, The Art of Forgetting, transfers images of classical statues from the Metropolitan Museum of Art into a domestic space mediated by technology. The video allows its viewers to circle the statues as Vogel muses on the act of remembering. Or is it forgetting?

The space also contains a number of prints from Vogel’s series What Death Can’t Touch, in which she inserts eerily lifelike black shapes into urban settings, perhaps a direct reference to the spectral presence of things which are no longer there and the idea of an erasure denoting presence, and a porcelain figurine from her series In the Absence of Bodies which explored the psychological and cultural ramifications of erasing reminders of the past (an issue of unforeseen relevance in the United States of 2017). The final piece in the gallery is Allahyari’s composite 3D printed sculpture of items forbidden in Iran, #dog #dildo #satellite-dish.

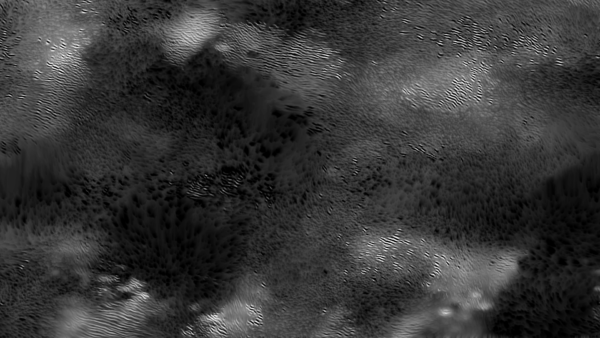

Back and Miller’s piece, Diffusion Imprint, consists of custom software-created visuals meant to resemble one chemical substance being added to another, the results of which are projected onto a large wall where viewers can watch the amorphous “liquids” shift and move, one image giving way to the next. Although I won’t pretend to understand how, the images create a soundscape which in turn is fed back into the visual component of the piece, each element altering the other in a circle of life-like feedback loop. The gallery also contains a series of stills from the visuals etched onto plywood, adding another layer to the already shifting notions of nature and technology present in the work: Are we seeing the specter of the super in the natural? Or is it that we’re seeing the natural in what is anything but?

In The Art of Forgetting Vogel’s narrator seeks places to hide her memories, a gesture meant to aid her in forgetting. “If monuments are built to help us remember, then their decay must imply our forgetting.” But that’s not true, is it? Technology actually ensures the impossibility of forgetting; past events are indefinitely memorialized in digital imagery that serve as stand-in for memory when memory fails or is denied. Of course as both Allahyari and Vogel know all too well, technology doesn’t only preserve memory, it has the power to recreate it, often in radically transformative ways. In their work technology makes the forbidden visible; it alters our perception of a past we’d often rather forget, and it can refuse us the luxury of forgetting at all — the desirability of which Vogel’s work pointedly challenges.

Technology also, as Avram alludes to in her curatorial note, sits at the intersection of humanity and spirituality; although it seems counter-intuitive, we’ve been thinking of technology in this vein for centuries, from our investing of machines with a sense of the magical in the Medieval period to our location of the sublime in technology and the machine in the 20th century. We have always located traces of the supernatural in tech.

In the 21st century the work of technology-driven artists like Miller and Back hints at the possibility of technology’s ability to actually evoke a sense of the spiritual. Despite our awareness of technology’s artifice at play in their work, Miller and Back’s direct invocation of natural processes in their visual and auditory loops, and the allusion to the organic in the woodcuts lining the wall, ironically prompts a sense of wonder located not in the technology, but in nature. Could technology actually inspire us to look again at the world around us? We know technology effects our psychology, but could it also touch our soul?

Maybe our inability to resign ourselves to technology’s presence in our lives — to make up our minds concerning its nature — lies less in the technology itself than in the ways we talk about, and therefore think about it. Maybe it’s simply a matter of harnessing technology to imagine and enact, as Avram puts it in her curatorial statement, “the possibility of magic and mythos amidst chaos.”

Through Oct. 15, 2017 at TWU’s East I West Galleries, Denton.

1 comment

Jennifer,

Thank you for a very thoughtful and meaningful review of the show and our work. It is much appreciated.

Martin