The Voice’s Folds, a program of eight experimental short films by Morehshin Allahyari, Michael A. Morris, and Jenny Vogel, had a single screening, recently, at the gallery Two Bronze Doors in Dallas. The narrative of each film is literary and personal, and is presented as text or voiceover. The pictures are stylized; they allude to but do not necessarily describe the words we read or hear. The tension that arrives from this willful disconnect of word and picture is the aspect that defines these films as experimental. A set of objects, a situation, a landscape, or a chain of events become the formula of a particular emotion, one that is tonally similar if not completely descriptive of events in the narration. Throughout The Voice’s Folds, words and pictures travel their close but separate paths to a common goal: connect the viewer to the artists’ experiences concerning place and lifespan.

Morehshin Allahyari’s film The Romantic Self Exiles pairs the filmmaker’s linguistic skills with computer-generated 3D landscapes.

Morehshin Allahyari, Romantic Self Exiles, Film Still

Allahyari favors latin-based words; these multi-syllable words create a sense of scientific precision, but the reference here is purposefully vague. The animated planes and geometric shapes that stand for wooded places and cityscapes, too, suggest a sort of scientific span of attention, but the lack of texture and specific qualities of light, situate this story in the virtual world and not the physical one. And so, what is the reference in this film? It lies somewhere between reminiscence and presence. Allahyari was born and raised in Iran and moved to the U.S.A. in 2007. The film explores ideas encrusted around the word “place” and ideas encrusted around the word “home”; words that describe public and private aspects of the individual. The film ends with the knockout line, “We no longer mean where we are from.” It alludes to a contest of cultures: the history of Persian culture; the formation of the Islamic Republic; the war between Iran and Iraq; the political and cosmological differences between Iran and the U.S.A. It’s interesting to compare that phrase with the idea Ernest Hemingway put in his war veteran Frederic Henry in A Farewell to Arms: “There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity . . . Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.” In a pessimistic sense, Allahyari, or her persona in the film, finds that even place names have lost their dignity; they lack the ability to maintain an ideological connection with the speaker. But in a different light, the phrase suggests a radical optimism, one that contests Hemingway’s realism with a poetic idea that the individual need not rely on physical boundaries to describe one’s journey of the self. History, even when magnified to the scope of personal history, is more open-ended than physical features can ever suggest.

The Recitation of a Soliloquy features diary entries by Allahyari’s mother. The entries were written during the Iran-Iraq war, when she was pregnant with Allahyari. Overlapping maps of Tehran and Dallas are projected over Allahyari in the present. The high key light of the projector washes out her features; one wouldn’t know just by looking what her situation is or where she is from. Allahyari wrote out each word from the diary onto individual frames of the film. The words are in Farsi, and they, too, are made ghostly by the high-key light.

Morehshin Allahyari, The Recitation of A Soliloquy, Film Still

Allahyari translated her mother’s words and put them as subtitles. More than an act of transcribing, she delivers her mother’s fears and desires from the host language into a new one. Those fears and desires describe a mother’s deep love for her unborn child. The daughter’s delivery of the mother’s words into English is poignant in the film’s final sentiment: the mother’s wish to deliver her child not in her home country but in the United States.

In the Realm of Rare and Analogous Accidents is, pictorially, a series of clips from cinema’s history. The narrative is a thoughtful voiceover by Allahyari about what Texas is like in the imagination of Iranians. The Howard Hawks film Rio Bravo dominates the discussion. It is a film that Allahyari’s father watched over and over. Part of Hawks’ great genius is the way he conveyed complicated moral decisions as fast-paced entertainment. I was interested to learn that Iranians associate the complexities of Hawks’ heroes with the moral character of American citizens. I confess it comes as a surprise that we in the U.S.A. rate much higher in the Iranian imagination than just grotesque, confection-addled caricatures in an evermore of shopping malls and digital gadgets. Another bonus, we get to see the Duke’s character speak to Ricky Nelson’s character in Farsi.

Michael A. Morris, Blue Movie, film still

Michael A. Morris’s aesthetic is built on visual noise. Camera flare, graininess, and color imbalance create layers of distortion that add distance between viewer and object. And yet, the distortion can also create a sense of intimacy. Film distortion has a close cousin in the sonic distortion of guitar feedback. Used skillfully, these distortions present an otherworldly quality to narration and song. As distortion creates distance, it can also act as an emotional and earnest form of utterance. The shuttle between close and far, intimacy and distance, mimics the mechanism of the camera shutter: open closed open.

The film Fires relates its narrative through title cards; they are grainy, given strange colors for light leaks in the camera lens, and written unevenly over each frame so that the text makes little jumps. The text is written by Morris and reveals his thoughtfulness and sense of wonder. What the title cards say (calm messages of inquiry) presents a different feeling than how they look (mad noise). The title cards and the point of view shots from behind the wheel of a car work together to make a character, someone thinking and moving around Dallas and nearby ranch land. It is not a character the viewer ever gets to see. Whether the character is Morris, himself, or a persona he created is not entirely clear. But the character’s message, I think, is not about identity so much as it is about inquiry. Watching the point of view shots of the character driving put me in mind of William Least Heat-Moon’s great travel book Blue Highways. Least Heat-Moon considered that: “Instead of insight, maybe all a man gets is strength to wander for a while. . . An inheritance of wonder and nothing more.”

Michael A. Morris, Fires, film still

The cityscapes in Fires are definitely Dallas, but not Dallas as we are used to seeing it. Color imbalance and light leaks through the lens create a visionary quality. I was amazed to see the city appear this way. What is more, Morris has manipulated the sense of time, and so what occurs in frame occurs at a strange and poetic pace. By using a very slow shutter speed, fast-moving objects like automobiles scarcely register in the frame; they are moving too fast to be captured by the camera’s slow shutter speed. What the camera catches of the vehicles is blurred taillights. They flash and then are gone, to be followed by another set of taillights; flash and gone. And so on in that way.

Fires features local news coverage of the blaze that destroyed Big Tex at the 2012 State Fair of Texas. Morris manipulates the footage with visual noise until the fire is given a hyper-real quality. Big Tex burns like some immolated giant out of mythology. The film ends with a projected image of 16mm film burning up inside a projector. The film blisters and falls apart. The apocalyptic urgency of the pictures in this film and title cards that suggest a panicked tone had me wondering if Morris was trying to achieve a prophetic voice, to deliver a warning all endeavors come to ash. But the end of times imagery is betrayed by the messages of the text, which are thoughtful and calm considerations about the passage of time. The tension that exists between picture and narration is skillfully controlled.

Confessors, along with other investigations, presents a mystery involving a can of 16mm film. Morris wonders does it really contain nude imagery of his grandmother in her youth, photographed on a Texas beach by his grandfather? That is the quiet rumor in the family, but Morris is hesitant to look, else the persona of grandparent be altered in an intimate—read, embarrassing—way.

Michael A. morris, Confessors, film still

In Confessors, Morris narrates rather than using text. His voice is friendly and intelligent; he is a good storyteller. His inquiry into the nature of the mysterious film canister is often hilariously funny. We are shown old vacation footage of rows of beach houses, their sense of fun heightened by the tall stilts. But there is also something wistful about the memory. Resort houses are much rarer since Hurricane Ike reshaped the Texas coast. With one storm, a way of vacationing with family has been greatly reduced. A persistent theme in Morris’ films is the effect time has on the individual; every connection is subject to decay. It’s a scary and yet beautiful realization we all have to face.

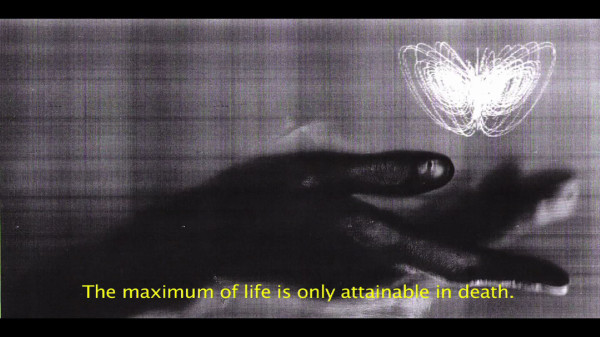

Jenny Vogel’s film The Beauty of All Things Falling is hospitable to actions of malfunction and decay. The central image is a hand, presumably the filmmaker’s. The “artist’s hand” is a familiar form of synecdoche. We use it more often than “the artist’s mind.” In this film, the hand is a character. It signals its motivations through gestures and has dramatic interactions with an object. The text that appears in subtitles is of a different mind, as it were, and tells a story about historical accidents.

Jenny Vogel, The Beauty of All Things Falling, film still

The hand image appears to have been created by an office photocopier. The background is an atmosphere of uneven ink and vague stripes made by rotations in the toner cartridge. Vogel uses stop motion to create a sense of movement. The hand performs its tasks against the rapidly moving background, which, for the stripes, passes like the boxcars of a train. It is as though the hand shudders for the effort of resisting this velocity. Vogel has created an animated object for the hand to interact with. At certain points, the object appears as a tiny model of the cosmos, a pendant in the shape of a mysterious symbol, and a butterfly, the hand may touch but not control the object. The text we are reading speaks of accidents, moments of innocence disrupted and altered into memorable, sometimes horribly tragic causalities. Like the object in the hand, history and lifespan never fall totally under personal control.

The Desert is in German with English subtitles. The narrator speaks to us as though she is an ancient seer. But this seer shows none of the curiosity typically so appealing in this sort of character. The poetry of this seer is listless, flat. This is a caged seer, one whose reference is the virtual world and not the real one. When she speaks of love, it is the unrequited love of virtual soul-barers who fail to meet in person at an agreed upon place and time. Perhaps each party was there, they just didn’t recognize one another.

We typically assume that the virtual word—the applications of text messaging, email and Skype—is, indeed, the real world, made closer and more convenient. Vogel’s film illustrates that this is not the case. Virtual contact lacks the magic and spirituality of real encounters. Vogel’s virtual world seer, unlike the seers out of legends, is doomed to a universe without Eros. Eros is by turns glorious and dangerously captivating. We might think we can iron out our relationship experiences by choosing what we reveal about ourselves online, but this level of control is wet tender. It will never spark the light of Eros, which seems so unpredictable; its moods of rejuvenation and uncertainty, power and despair, are lights within our eyes. For the sad sacks depicted in this film, the light of the eyes is reflected off computer screens.

Jenny Vogel,The Desert, film still

The Desert is shot entirely on web cameras. These create awful visuals. Vogel is acting a contrarian image-maker. She wants us to imagine the inverse of these images: people by turns in light and shadow rather than caught in the saddening glow of an online camera; landscape with contours and color variations rather than the web camera’s compressed fields of fixed focus vision. By seeing the bland, we yearn for the vivid. In this way, Vogel fulfills the inversion; not on screen but in the mind. The web camera’s sensor cannot capture a spirit of Eros. But we, the viewers, can allow it into our open minds. This spirit is our way out of isolation, out of the wasteland the film describes.

Each of these filmmakers prefers visual noise to clear pictures. Given the many ideas in these films, the effect of watching them all together (73 minutes) is like traveling across interesting landscape with a dusty windshield. The clips from Rio Bravo act as something of a foil. Hawks presented large themes with sharp images, whereas images in The Voice’s Folds are often vague for their distortions. But here is a crucial difference between mainstream films and experimental ones; a filmmaker like Hawks is interested in metaphors and archetypes. Hawks was reluctant to articulate this point, but his films showed an awareness that the emotions, tragedies and victories of any age are reducible to specific characters and settings. He knew that shaping these metaphors and archetypes with skill allowed audiences to recognize themselves and the story of the world.

An experimentalist isn’t so interested in a world reduced to symbols. Rather, the experimentalist operates knowing that not all experiences that come from ideas like nation, family, love and memory can be reduced to a set piece or character type. Allahyari, Morris, and Vogel are interested in the vagaries of experience. With The Voice’s Folds, they present variations on a familiar but uncomfortable idea: the picture of the world we see has only a tenuous relationship with the language we create to describe it.