As I grow older, I sometimes feel despair that life has not ordered itself into a tide pool where the ebbs and flows are regular like a metronome. Instead I still live on the rocks hit by the waves. But to live on the rocks is to see all the other people there, struggling not to slip, and there is some solace in not being alone in that struggle. By now the hypernormalization we live in has become rote — the world is becoming better, richer, more technologically advanced, less starvation, better food and restaurants, and on and on. And yet, life seems harder for most of us: jobs pay less, things cost more, Cool “A” cities like New York, San Francisco, Seattle, etc., are increasingly sealed like lacquered furniture, and are essentially highly refined corporate office parks owned by a handful of people who the rest of us pay for the privilege to work and temporarily stay in. With this come stress and desperation which robs us of one of the attributes that separates humans from other animals — the freedom to dream and tell stories.

This is the reason I have scaled my life backwards on the curve of the globe, moving from Beijing to Austin to San Antonio. When I am in the A cities, despite the sophisticated food and museums and beautiful hipsters, I wonder how cool a city can really be when it’s populated almost exclusively by rich white people. And I wonder if all the cities the people of my generation have dreamed of leaving could become some of the only places in the encroaching neoliberal thunderglobe where one could have the leisure to dream.

I had been planning on visiting my friends, the musician Jesse Jenkins V and the artist Ashley Thomas, in Corpus Christi for some time, to write about their work and the coastal city they live in — a serene, dreamy and roughly beautiful city of 400,000 people, which exists for now mainly outside of the billowing forces of hipster gentrification. Since Hurricane Harvey, I’ve felt even more drawn to the coast, as Texas feels like its own insane country and the coast is where we have holidayed since we were children, and when a hurricane hits, its physical destruction attacks our memories, and the days in the aftermath have a hollowed and wandering quality. Thus, I packed up with my trusty photographer Twisted Sam and headed down to the coast.

I’ve been going to the town of Rockport, 30 minutes from Corpus, since I was a child. My family has an ancestral home there, built in 1868 — a canary yellow Greek revival, with 20-foot-high ceilings and an exceptionally chill ghost. I’ve had many good times in the sweet, sleepy town of Rockport, which was hit directly by Hurricane Harvey. Our house sustained some serious damage but was relatively intact, but much of Rockport is devastated. An unsettling bolt runs through a town after a hurricane — a bolt that turns to a shell-shocked weariness, as if you went to sleep one night and slept for decades and when you awoke everything around you had been blown away. It will be years before Rockport recovers, but Texans have a pragmatic hardness about their state, and how it tries to grind you into dust. Many Texans say they don’t believe in global warming, but their stoic response to the increasing frequency of such once-in-500-year storms, their genuine community solidarity and response suggests that on some level we know we are now living it.

Corpus Christi was mercifully spared from the brunt of the hurricane, and while many piers, signs and trees were ripped away, the city doesn’t look like the blasted bay hamlets that surround it. Corpus was nearly completely destroyed in the great storm of 1919, and subsequently a seawall was built and the city over the decades has braced itself again and again. To live in the so-called “Hurricane Alley,” especially as we enter the strange new age of the slow rolling ecological catastrophe — the satellite imagery of hurricane after hurricane in clipped quarter spin like videogame tumbleweeds — is to process the malevolent immediacy of life a bit ahead of the rest of us. That something may be coming for you out of the sky, and there would be no justification for why it came for you.

Jenkins is a founding member of the louche, hypnotic band Pure X, whose three albums (Pleasure, Crawling Up The Stairs, and Angel) form as coherent a narrative statement as the first three Wire albums, or the triptych of ’70s country funk albums by J.J. Cale. Thomas received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and works in meticulously detailed, dreamily surreal works with pencil and graphite dust that appear as open doors or windows one could step through. After they married they decided to move from Austin to Corpus. Houses there are much more affordable, and Thomas grew up there and Jenkins liked the relaxed, uncrowded atmosphere of the city that allowed for some creative serenity. They bought a charming ranch house in a pleasant neighborhood and ripped up the linoleum in the kitchen to concrete and lacquered it with white epoxy and a flower petal design by Thomas, so it’s now smoothly cold to walk on, like marble. They each have their own studios — Thomas has the airy converted garage, and Jenkins a room in the house with the drifting scent of sandalwood and a framed rattlesnake skin on the wall above a rack of synths.

Jenkins, under the moniker “Jesse,” released what will probably end up being my favorite album of 2017, Hard Sky. It’s a lush, elegiac album that is both an expansive drift through the clouds, and deeply emotionally resonant. Driving out to Padre Island National Seashore, a 60 mile stretch of beach with nothing on it and few visitors, the sky was a pale purple and hung low like the shelf of a canyon, and Jenkins remarked: “When I think of the Texas coast it is always overcast in my mind.” Later, as we bobbed in the waves at the completely empty beach, I marveled at the solitude, and he replied, “It’s about solitude.”

Like Hard Sky, Corpus has a flintiness to its leisurely environment. Driving back from the beach we saw a routine Corpus sight: a shredded, heavily tattooed shirtless man bumping music off his phone, and in this case riding a bike with a crossbow fishing spear over the handlebars. The city’s downtown, where the turquoise tinted statue of the martyred queen of South Texas, Selena, presides, is significantly vacant, and many of the sunbaked buildings have a sand-coated beauty. It’s easy to dream about moving here and opening a casual dub bar or a small theater that played movies like Rolling Thunder and Wake in Fright.

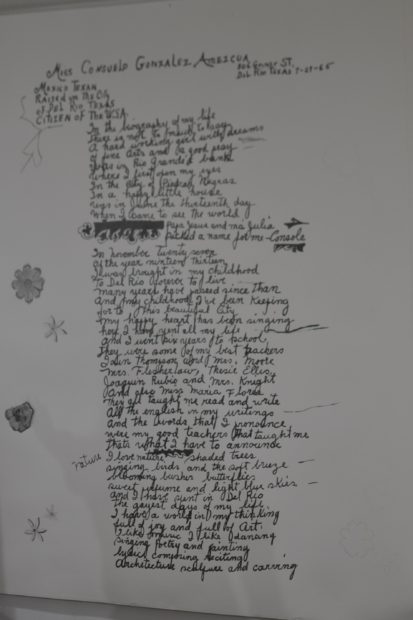

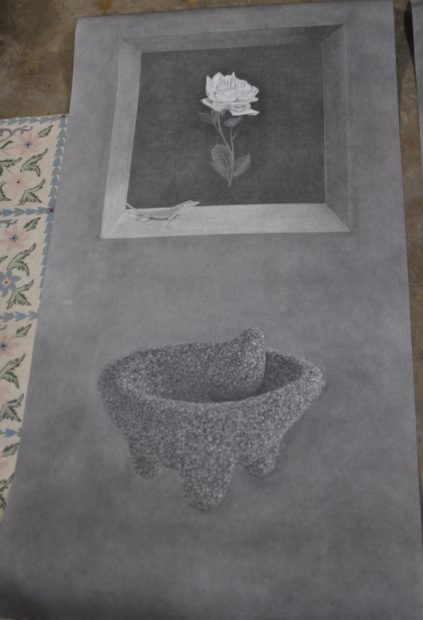

Later in the evening, I visited Thomas’ studio to see the pieces she was finishing to show at the Invitational Mexican-American Perspectives Exhibition at the Joseph A. Cain Memorial Gallery in Corpus (it opens September 15th). Consuelo Gonzalez Amezcua Autobiography takes a poem by an outsider artist from Del Rio in the first half of the 20th century, enlarges it and adds exquisitely wrought flowers and other objects in the margins. The poem is plaintively haunting and begins: “In the biography of my life there is not to much to say [sic],” and towards the end is the line “I have a world in my thinking full of joy and full of art.” These two lines are the bridge of the human experience. It’s a bridge that leads to Thomas’ staggering dream windows of the diptych Molcajete and Mal de Ojo, which depict, respectively, a mortar and pestle, and a glass with an egg in it (a cold egg for the Ojo folk remedy) beneath a window where lizards perch that looks out onto floating white roses. The diptych is gorgeous and charged with a mysterious current of emotion. Thomas told me that after she made the piece, her mother told her how she used to eat rose petals from the window when she was hungry. In these works, the past and its struggles and sorrow entwine with the perfect dream in the mind of a floating rose — an ineffable beauty just out of reach. This coexistence is present in Thomas’ and Jenkins’ works, is present in the salty, heavy air of the coast, and seems increasingly necessary as an armor to survive in these end times.

My favorite song on Hard Sky, Cinco’s Lament, is a sad-yet-affirmational croon that I wish I had heard during a difficult time in my life when I spent far too much time lying in bed when I wasn’t tired. Its lyrics form a contradictory mirror:

“I don’t know if I can stay

Living this kind of life anymore

Nothing else that I can do

Gotta keep on doing it

When I feel like I wanna cry

I don’t know if I can stay

Living in this lonely town another day

I don’t know where I would go

I just know I gotta go

When I feel like I wanna cry.”

As the future unfolds before us — a scorched desert of ecological catastrophe, insurgent white supremacist fascism and terror, and crushing economic neoliberalism — it is clear that we must endure and change. We “gotta keep on doing it” and we “gotta go.” And you may feel like you want to cry while on the beach, watching the light drain over the horizon as the waves roll in.