Earlier this month, Houston’s Station Museum of Contemporary Art opened Torture, a show of works by American artist Andres Serrano. The exhibition consists of large-scale photographs, many of which were created in a 2015 project initiated and produced by a/political, a London-based non-profit organization that works with socio-political artists. For this series (also titled Torture), Serrano, under the guidance of military personnel, worked in the town of Maubourguet, France with more than 40 models to create images that showed his subjects being tortured both mentally and physically. He also photographed medieval torture devices, concentration camps, East German prisons, British Immigration Detention Centers, and four of “The Hooded Men.”

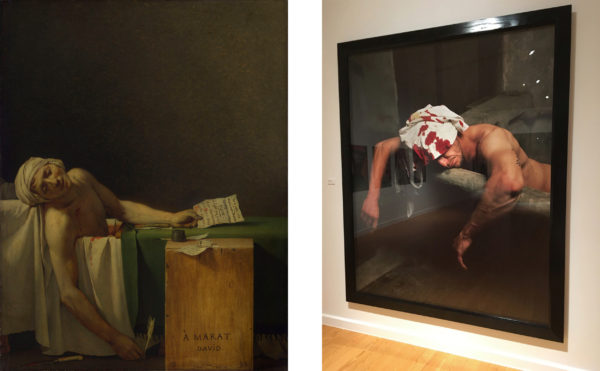

The pieces in the show of course evoke earlier images of war and political upheaval. Serrano’s Untitled XIV is a photograph showing a man draped over the side of a tub with his head wrapped in a bloodied cloth. Here, the artist draws on the composition of The Death of Marat, a 1793 painting by Jacques-Louis David depicting the murder of the radical French journalist. Other effects are subtler: Serrano’s torture photographs are spotlit and staged in a way that recalls Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro. And this is where some of Serrano’s images begin to lose their impact.

The works Serrano created in Maubourguet are less shocking than I thought they would be. I think the reason for this is two-fold: One, the internet has caused us to become unsettlingly desensitized to violence overall; and two, we have been exposed to real torture imagery in recent years. Perhaps the most widely seen real torture photographs is the set of grainy images from the Abu Ghraib prison that went public in 2004. They were shocking then, and they still are now. The power of these photographs is in their candidness and their unabashed undermining of humanity. Recall that in multiple images, a soldier (who was later imprisoned and dishonorably discharged), uses a leash wrapped around a prisoner’s neck to drag him around the prison. In others, naked detainees are used as hooded props as soldiers look into the camera, give a thumbs up, and smile.

Though the text for this show says Serrano’s subjects were tortured, the images in the exhibition feel too pristine, too clean. Other pictures from the Torture series, which are in a video montage and in the show’s catalog, come closer to the brutality of the Abu Ghraib images, but they still fall short of causing the distress of looking at the real thing. While this means Serrano’s photographs are easier to stomach, the staged quality undermines their power.

Other images from the Torture series make more of an impact. The larger-than-life photographs of the East German Stasi prison put you inside creepily kitsch interrogation rooms outfitted with patterned chairs and lace curtains. These scenes are juxtaposed with a fluorescent-lit hallway of open cell doors and an image of an open gate. Accompanied by wall text explaining the history of the prison, the figureless images allow us to project horror stories into each of the rooms. What were the “extreme interrogation techniques” used by the Stasi, and how could its officers have committed such heinous actions in these cheerfully decorated cells?

Other standouts in the show are a series of four photographs commissioned from Serrano by the New York Times Magazine in 2005. Taken originally to accompany an article by Joseph Lelyveld, one photo depicts waterboarding, two show figures with bound hands (one with handcuffs and one with a tiewrap), and one shows a hooded figure. Drawing on effects used in fashion photography, these images depict torture in a way that takes away some of its nastiness, but if you look closely, some grit remains though attention to detail: the tiewrapped fists show a trickle of blood coming off the prisoner’s wrist. While I do think there is a danger in an artist (inadvertently) taking power away from a subject that holds so much weight, I don’t have a problem with Serrano’s torture photo shoot because I see it (as the New York Times must have) as an entry point for those ignorant of torture practices. And with torture, the conversation matters.

So while some of Serrano’s photos didn’t have the impact I expected, in the end, they forced me to rethink torture overall—by looking at the fake, I had to confront the real. Both Serrano and the Station strive for this kind of conversation—it’s their strength. And subsequently, the book of the Torture series, published on occasion of Serrano’s exhibition at the Collection Lambert en Avignon, is the best way to engage with these photographs. The series needs to be seen as a whole, and the images need to be contextualized through their relationship with each other.

I have gotten this far without mentioning the elephant in the room, but I will here: The show includes Piss Christ. You can’t have a Billy Joel concert without Piano Man, and evidently you can’t have a Serrano exhibition without his infamous 1987 photograph. Nearly all of the press about this show has been centered on the fact that it includes both Piss Christ and the artist’s 2004 portrait of Donald Trump. From an article in The Art Newspaper to a post on the conservative website Truth Revolt, the focus has been on Serrano’s contentious history with Christianity and the grant money he received from the NEA. But we need to move past this—1987 was 30 years ago, and it feels like Serrano has moved on and wants to have a different conversation. And we would be fools not to take this show as our chance to address some bigger issues in the world.

Through October 8, 2017 at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston.