Tucked away in the woodsy northeast region of Texas is the Tyler Museum of Art, a small and pleasant space that for the past year or so, under the curatorship of Caleb Bell, has been hosting smart, with-it exhibitions highlighting deserving Texas artists. From helping organize the exhibition of a recently restored mural by John Biggers, to curating a show of paintings by Forth Worth artist Daniel Blagg, to a summertime-themed group show of works by Shannon Cannings, Leigh Merrill, and Kelly O’Connor, Bell has been making an effort to connect Tyler to the Texas art world at large.

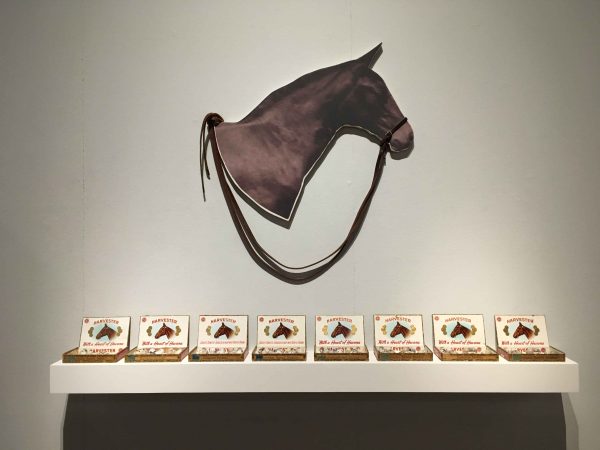

The show currently on view at the museum, Sticks and Stones: Works by Helen Altman, is quiet and contemplative, featuring works created by the Fort Worth-based artist throughout her career, particularly from 1992 to today. The show is organized around pieces from Altman’s oeuvre that specifically depict or comment on the various facets of nature as we humans know and experience it: wildlife, domesticated animals, hunting, the outdoors, the fragility of life, and the volatility of fire all come into play in the exhibition.

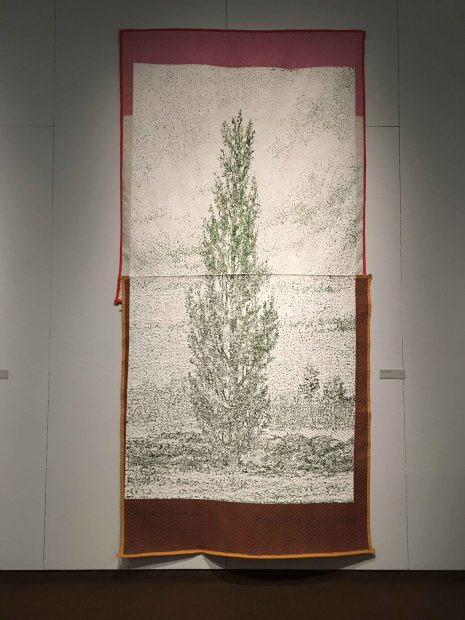

Lombardy Poplar, 1999. Acrylic on moving blanket

Installation view of Sticks and Stones: Works by Helen Altman

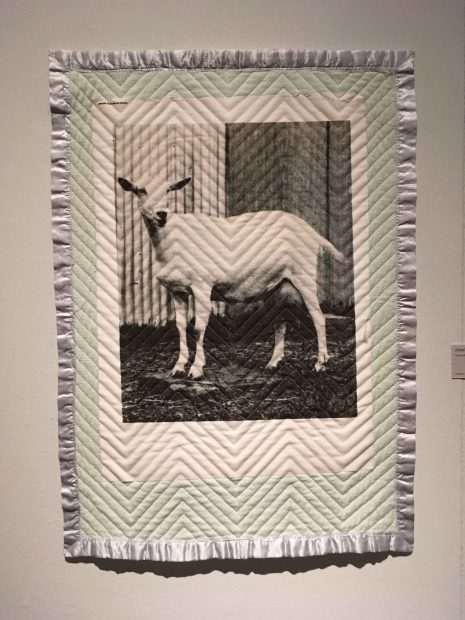

Small Blanket (Goat), 2016. Thermal transfer, quilted vintage baby blanket, thread

Corner Campfire, 1992. Birchwood, paint, plastic, misc. elements

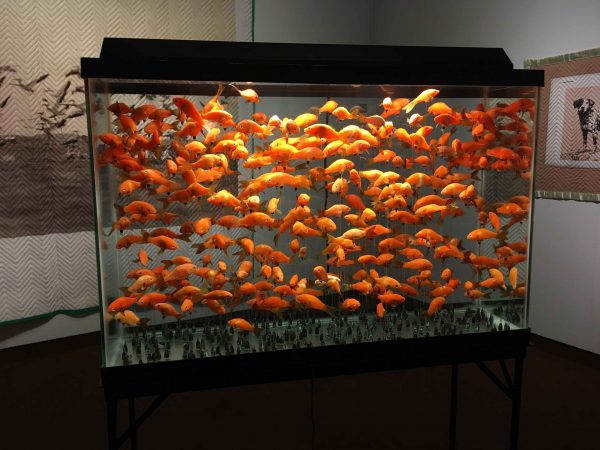

Another of Altman’s hallmarks is toeing the line between perfectly crafted objects and things that are well-made but just slightly off. She writes:

“I am also interested in mimics and replicas. It is a happy moment for me when I can create objects that are simultaneously convincing and yet blatantly absurd in their obvious artificiality.”

Goldfish, 2009. Cast plastic, epoxy, lead weights, monofilament line, 45-gallon aquarium & stand, distilled water

Installation view of Sticks and Stones: Works by Helen Altman

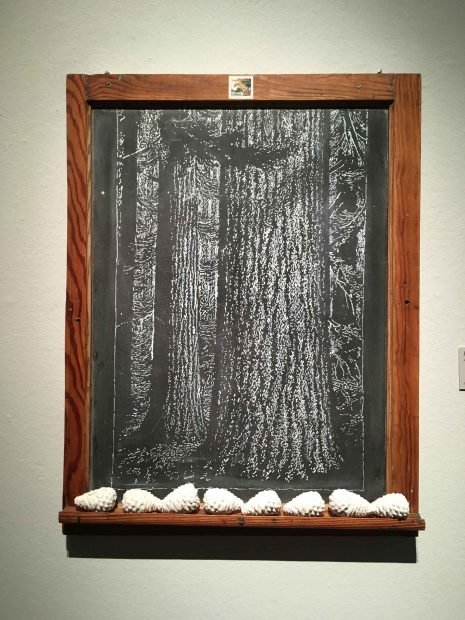

Rods & Cones (The Red Fox), 2018. Acrylic on vintage chalkboard, cast plaster, laser print

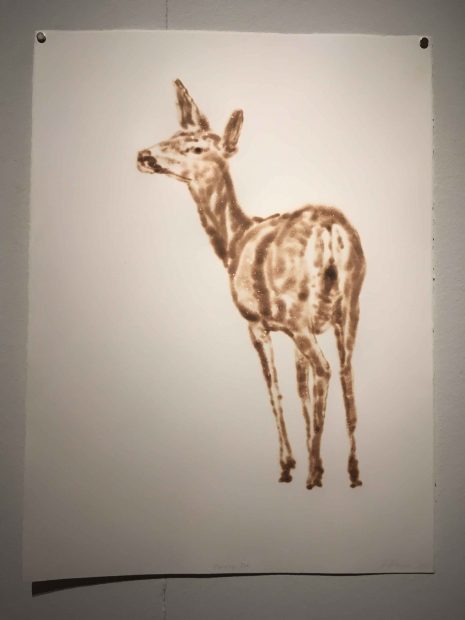

Turning Doe, 2017. Torch drawing on paper

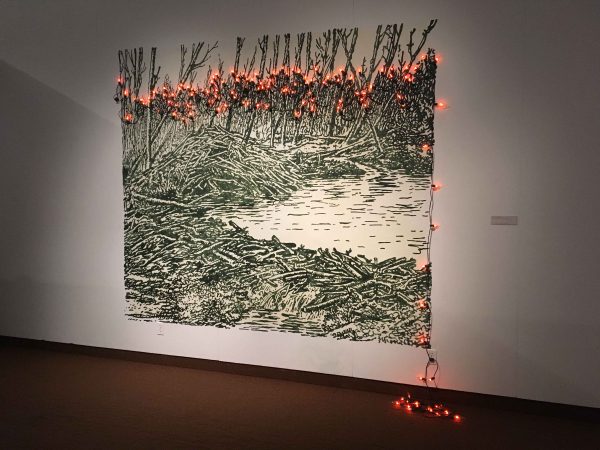

Line of Fire, 2011. Acrylic on wall, flicker flame bulbs, misc. elements

Installation view of Sticks and Stones: Works by Helen Altman

Altman has been due for a large-scale institutional presentation of her work — it’s been a little while since she’s had a big non-profit show in Texas. For me, this one made all of Altman’s practice click into place — to fully appreciate where she is now, I needed to know where she came from. And whether you love her work or not, this show might just change the way you see it.

Sticks and Stones: Works by Helen Altman is on view at the Tyler Museum of Art through June 3, 2018.

3 comments

I travelled to Tyler from Dallas to see this lovely show. Beautiful and quirky sensibility. Well worth the trip.

Altman doesn’t let her love of nature blind her to its cruelties.

As a kid, my brother and I raised a pair of white ducks. They were probably Easter ducks but when they were grown, my Mom and my brother and I took them to a lake we visited often. We set them free. It was called State Lake for a long time, and later named Lake Lurleen after George Wallace’s wife. I grew up in Alabama after all. And when we went to check on the ducks a week later. We looked and looked. Leaving the lake, I saw them both dead on a trash heap next to the road. “There are our ducks!…and they are both dead!”, I screamed from the back seat. Sorry about the punctuation, I’ve probably gotten it all wrong but to this day, I still see those dead ducks on a trash pile leaving the lake.

Thank you for writing about my show. Caleb Bell deserves all the credit for picking the right works.

oops! It’s “whether” not “weather”. But otherwise a good review.