Artpace’s long-running, thrice-yearly Artist-in-Residence exhibitions are always a highlight event in San Antonio because when there’s a synergy between the curator and the artists (always one international, one national, and one Texan artist), the show aligns as one multifaceted text. In the current show, curator Michael Smith brings three formally different artists together whose works all question and disrupt the latticed systems of societal control.

On the second floor, Martha Wilson, a legendary feminist artist active since the 1970s, displays in her show Political Evolution an arresting series of photographs of herself dressed as political figures, and in one series she hypnotically transitions into Melania Trump. There are images of Wilson as Barbara Bush, Bill Clinton, and of course Donald Trump. Her Trump is simultaneously flaccid and bloated — the makeup and lighting give his skin the appearance of a condom made from the same material as Chicken McNuggets. His expression and double thumbs up feel mid-deflation. In other words, she totally nails it. Likewise, right above (by no accident) Trump, Wilson’s Bill Clinton has a ghostly, unsettling demeanor. Shot in black and white, Clinton has a sunken lecherous grin like Robert Blake in Lost Highway. With a seemingly real sea-change happening around the awareness and consequences of sexual misconduct, and the reckoning of Bill Clinton’s past lost in the winds, Wilson’s Clinton is the leer of power and complicity.

The series of photographs of Wilson’s ghostly transformation into Melania Trump are more empathetic. In the final photo in the series, Melania displays her usual rictus of maintaining some hyperventilating ideal of Aryan beauty — a rictus that seems so perpetually exhausting as to render Melania a particularly bleak cypher. The first photograph in the series, of Wilson, is enormously relatable. With a split, dyed haircut and an expression of wry sadness, Wilson is wholly human, and like the best photographic portraiture, shows us a visual evidence of a soul. The transition is an elegy and an outrage that marks the toll of the mask.

The French artist Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s movie Beyond The Land of Minimal Possession is screened in a room covered in crimson carpet, and viewers are encouraged to lie down for the 90-minute duration. Set in Marfa, Texas, the highly experimental, often unsettling film explores the idea of gentrification and the way the art and the commerce intersect and entwine. Marfa, after all, is one of the strangest cases of gentrification in the past few decades — almost as if the whole place were an art project, the years-long installation of an egomaniacal alpha obsessed with purity and symmetry. The film contrasts day and night scenes. The former consists of documentary like scenes about the development of Marfa, and the actors engage in highly performative simulations of “The Marfa Experience,” e.g. afternoon cocktails at the Hotel St. George, traipsing around the Marfa Bookstore, etc. The nighttime scenes are vampiric and hallucinatory; the actors wear Dawn of the Dead-like face paint and lurch around the town in a George Romero-like shuffle. It’s a long, challenging piece that takes you to some uncomfortable places involving art and consumption.

Heyd Fontenot’s Unnatural Urges is an elaborate, kinky, multi-room theatrical stage that feels like a bordello in an early ’60s Kenneth Anger film. At the opening, Reynaud-Dewar, wearing a tuxedo, danced on the bar to a French version of Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit and a shirtless actor wearing chaps with black eye makeup stoically flicked a bullwhip. Needless to say, I heartily approved of the vibe.

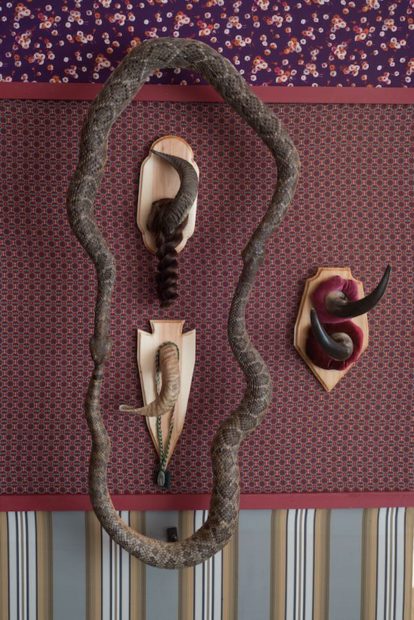

The installation is crammed with detail: tusks, taxidermy, furs, whips, and chains. Its tumescent eroticism is offset by its intentional artificiality — the installation floats in the middle of the room; the floors have pastel, trapezoidal patterns recalling the set of Pee-Wee’s playhouse. Fontenot is dealing with the fragility of domination and the sets required to maintain the illusion of control.

Taken together, the three shows are concerned with performance: the performance required for entry into society; the performance of one’s self in the constructed world of others; and the private performance. You may never stop acting, but sometimes you can see the stage.

Through Dec. 31, 2017 at Artpace, San Antonio

1 comment

boom, heyd!