Will Henry is a good painter. Over the last decade the Houston artist has developed a specific, personal approach to image making that is grounded in the history of landscape painting and is concerned with contemporary questions about painting’s possibilities as a form of communication. Remote Viewing, Henry’s show of 13 small landscape-based paintings at Hiram Butler Gallery in Houston reminds me why painting and drawing are still the art forms against which every other form is measured. Nearly 40,000 years old, painting is one of the most complicated and enduring manifestations of human consciousness. With a little bit of colored mud or the end of a burnt stick, human beings have been able to transfer immaterial, mental pictures from their minds onto the physical, visible substrates of cave walls, sheets of paper and stretched canvas.

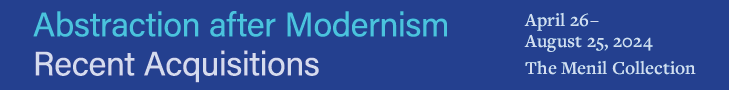

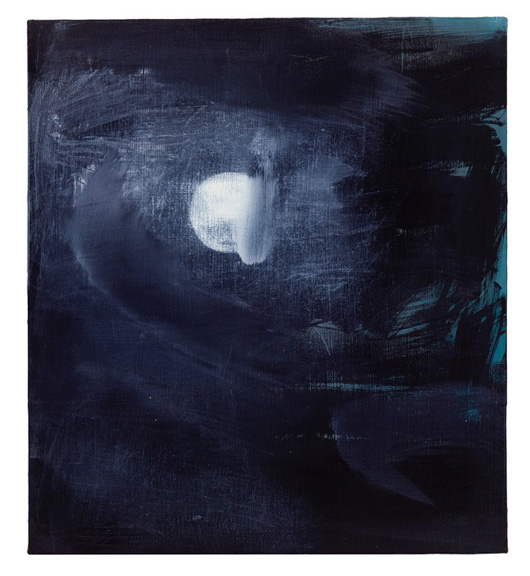

Henry’s subject matter, the psychological clothes hanger on which he drapes his painting process, is the rural outdoor landscape in which he grew up and which he says has been “imprinted on his psyche.” While scenes of wilderness and open countryside lend themselves to notions of the Romantic sublime, Henry’s sublimity isn’t located in the vast openness of Turner’s 19th century. Several of his landscapes are framed through window-like structures, but even in those pictures, without such a framing device, Henry seems to be on the inside looking out. Henry’s landscapes are mental pictures, built from memory and made physical by the unpredictable application of paint on canvas. He doesn’t refer to photographs or specific source images to generate his images. The window pane from which Henry simultaneously peers out and looks in is his own mind.

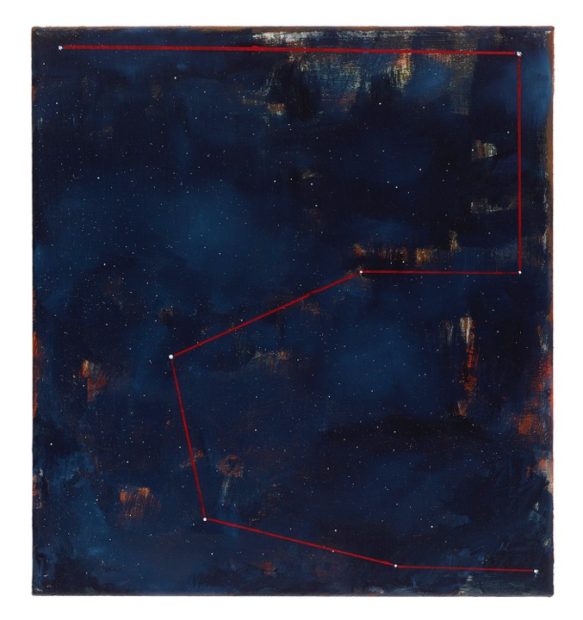

A painterly style is a representation of the character of the consciousness of the painter. From my perspective, there’s a touch of mysticism in the way Henry’s mind works. It shows up in his authentic—but gently, often humorously—subverted commitment to the aesthetic sublime. The viewer is invited, through a representational fantasy, to indulge in transcendent, even spiritual thinking. But Henry’s mystic predilections are ultimately grounded in the physical qualities of paint. The narratives embedded in his landscapes are always closely tied to a brushstroke or a smear that refuses to be anything but a brushstroke or a smear. Look long enough and the paint itself becomes inseparable from Henry’s subject matter.

The emergence of new ideas in a painting is like a scientific discovery; they’re prompted by accidents, mistakes or misunderstandings that occur within defined parameters. Accidents in Henry’s paintings are collisions between one fairly rational decision and another. These collisions happen when, for example, in Untitled, gold paint is pulled down along the edge of the canvas over a patch of blue-green paint, not quite covering it. The blue layer, visible through the gold, breaks the illusion of the picture frame the gold paint is meant to represent. Henry chooses to leave this disjunctive moment visible. Frame and picture are one. The gold frame is revealed as an illusion but its cropped absence on the right side of the painting makes it seem even more real.

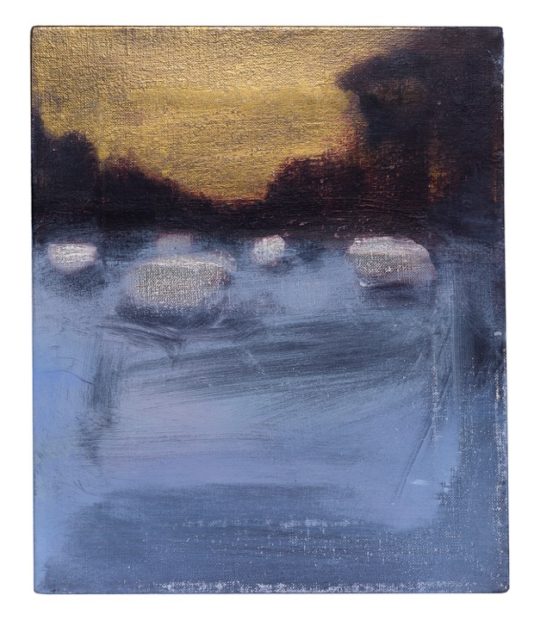

Henry’s work is full of these kinds of conscious, fine-grained decisions. In Ruins in the Mist, a moody homage to Symbolist landscapes, five grey stone-like forms, which seem to be emerging from or floating on the surface of a cool patch of blue paint-water, are formed not by heavy paint but by exposed canvas. These five round shapes sit visually on the surface of the picture plane but are pushed forward by the fact that they are the exposed linen substrate of the painting. There’s a poetic play in this representation between rocks as the substrate of our planet and canvas as the substrate of the world of painting.

Making a painting is not just a visual process. It requires a sensitivity to touch as well. Painters judge their moves in the arena of the canvas as much by the feeling of resistance the paint and brush communicates to their hands and arms as they do by looking. When I look at paintings, I try to retrace the painter’s decisions. I ask myself which layers came first, what was planned, and what was a happy accident that was recognized, saved and expanded upon. There’s an exciting moment in the top left corner of World Out My Window where I suspect that a small clump of paint is the result of painting and repainting the picture’s reddish-brown border. The paint displaced by the smoothing of the surface is carefully collected where the brush stopped and is left as evidence of that action.

The foundation of Henry’s work is materialist, but he continues to hold on to the imaginary by guiding his physical paint application through his memory of specific images. His refusal, or inability, to abandon representation and its connection to his personal experience points to the idea that Henry sees himself as an individual with a specific point of view based on his personal experiences. His mental images are not reducible simply to shapes and colors. For Henry, these formal elements have to cohere in an image that allows him to stand somewhere in the observable world.

Good contemporary representational painting sets up illusions and acknowledges that they are illusions by exposing the medium through which they are achieved in a way that doesn’t destroy the fantasy, but, in fact, causes the viewer to strain toward it, through the material dislocations. Henry’s paintings remind me of William James’ description of the ineffable. In it people struggle to find ways to communicate mental ideas and almost always come up short. The abrasions, the scratches, the mounds of paint, the streaks, the smudging and smearing in Henry’s landscapes of the mind are the scars, distortions, and glitches in the incomplete mental picture from which he draws.

Doing good painting is like to doing good philosophy. Both philosophers and painters tell stories and make propositions, based on personal experience and the scientific and philosophical knowledge of the day. They ask what it means to be human and not any other thing. What does it mean to be able to process sense-memories of the past through the physical medium of paint in the present, in order to create representations of a mental world that only exists in the mind? Henry does an eloquent job of asking these questions. As always in painting, it’s up to the viewer to find his own answers.

Through Jan. 7 at Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston.

1 comment

Thanks, Michael, for an excellent article on an excellent painter. Will Henry is the real deal.