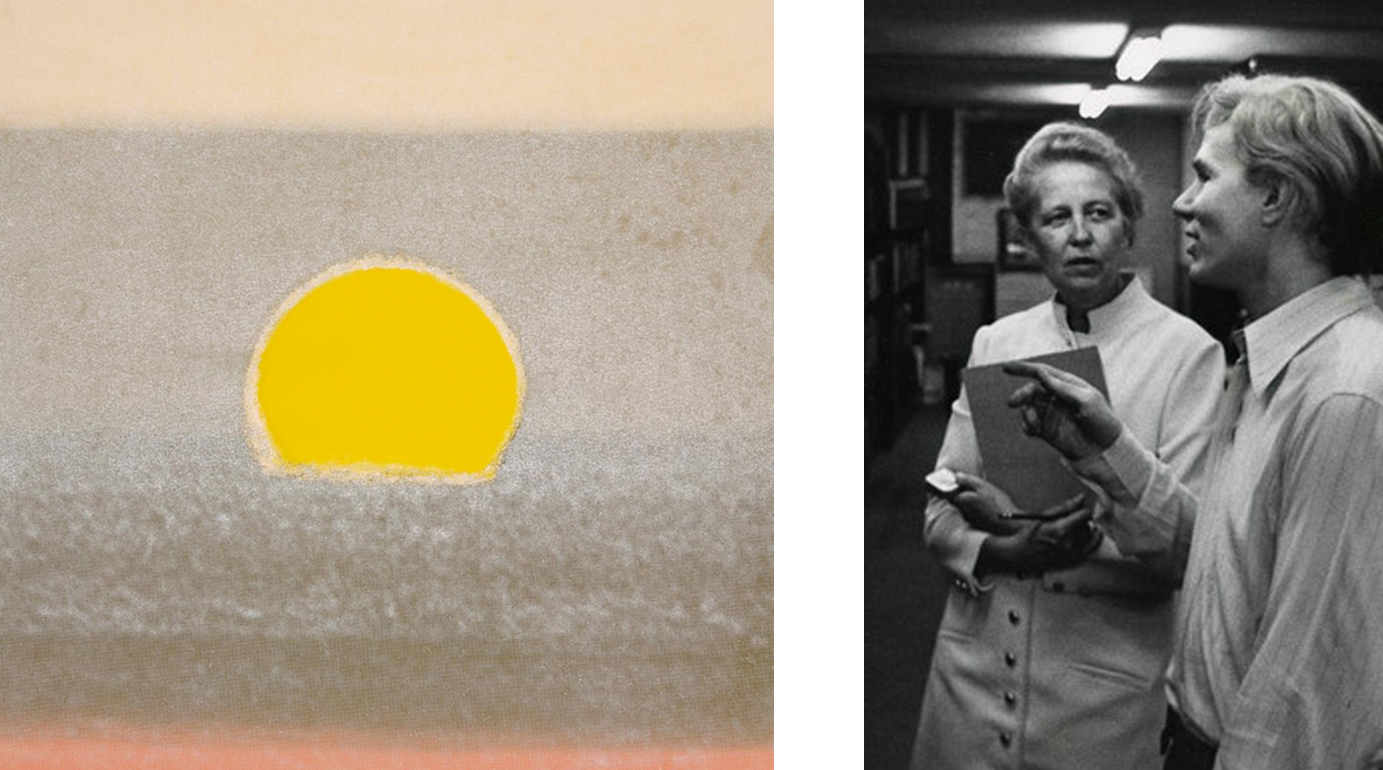

Film still from Andy Warhol, Sunset, 1967. 16mm film, color, sound, 33 minutes. © 2016 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Film still courtesy The Andy Warhol Museum.

We tend to think of cultural innovation coming through fixed masterpieces that realize one artist’s particular visions, defined ideas, intended meanings. But I’m fascinated by the great many ideas that have evolved more slowly and fuzzily over time, having navigated less rigidly-defined ambitions, mixed inspirations, experimental play, obsessive reworking, failed attempts, and sometimes the contributions and constraints of unlikely collaborating forces. Those kinds of origin stories seem more interesting to me, and the outcomes often more miraculous. This was on my mind as I spoke recently with Menil Collection Curator Michelle White about the museum’s unique exhibition of Andy Warhol’s unrealized Sunset film (which just opened last Friday) and as I read through archival materials relating to the project’s origins in the late 1960s.

A bit of background: Houston-based collectors and philanthropists John and Dominique de Menil considered art to be a central part of the human experience. Their Catholic faith and interest in ecumenicalism informed a humanist approach in their endeavors as well as a deep interest in the intersections of art and spirituality. They had founded the Art Department at the University of St. Thomas and had commissioned Mark Rothko to create paintings for a permanent installation in a planned non-denominational chapel space, when Dominique de Menil was asked by the Catholic Church to organize the Vatican’s pavilion for San Antonio’s upcoming World’s Fair, HemisFair ‘68. Dominique, John, and assistant Fred Hughes contacted a number of contemporary artists about creating progressive works of some spiritual significance for this “ecumenical pavilion” at HemisFair and arranged for Houston architect Howard Barnstone to design its structure. “Art and religion actually speak the same language where a true artist is involved—regardless of his own religious position,” John de Menil explained in an early correspondence about the project. Robert Indiana, Tony Smith, and Roberto Matta responded with ideas. But it was Andy Warhol, a devout Catholic, who was the first and most enthusiastic to respond with specific ideas for a new project: a multiple-screen film of sunsets and sunrises.

Warhol had focused his efforts primarily on filmmaking since the early ‘60s, experimenting with real-time static shots of “everyday” images and actions (Sleep, Empire) and, especially in the few years before this project, multiple-screen films (Chelsea Girls) and environmental projections (the films and light at his Exploding Plastic Inevitable events). I’m of the opinion that his proposed series of multiple color static shots of sunsets and sunrises, installed in a dedicated space for visitors’ contemplative experience, might have been the greatest confluence of Warhol’s work in paintings, prints, films, and environmental projections. The sun is, after all, the literal “superstar” of our visible world, while its slow daily arrival and departure from view the most essential and universal of “everyday” occurrences. The installation would have connected his serial 2-D works and temporal film imagery, as well as connecting the surface of Pop with depth of the beyond. That is, if it had happened.

Robert Indiana’s poster for HemisFair ‘68

The project fell through. Warhol wasn’t completely satisfied with any of the five or six sunsets he’d filmed, and meanwhile the HemisFair project caved in due to logistical problems. Nevertheless, the de Menils continued to support creative efforts that came of the project, and in fact they seem to have been relieved by the lifting of its tight timeline and outside constraints. In a letter to Roberto Matta, John wrote, “There is no urgency since the project is no longer tied to the HemisFair in San Antonio. Just let your heart flow into it and when you are ready, let us know.” Robert Indiana designed a poster for the HemisFair, and then completed his originally proposed commission, Love Cross, the following year. Though Warhol’s intended project was scrapped, he incorporated the best of his sunset footage into his legendary 25-hour multiple-screen film event titled “****” in New York in late 1967. He used the remainder of the funds from the project to produce the film Lonesome Cowboys, which premiered in Houston in April of 1968 with Warhol, Paul Morrissey, and Viva in attendance. The following year, he gave to the de Menils two Big Electric Chair silkscreen paintings in gratitude of their support and returned to Houston for a show organized by Dominique de Menil at Rice University. He also revived the sunset imagery for the basis of a series of prints made in 1972. Typical of the efforts of the de Menils and also of the creative process of Warhol, this “failed” project actually produced numerous reverberations in the form of ideas, artworks, relationships, and cultural connections.

One of Warhol’s Sunset prints, 1972. R: Warhol and Dominique, 1969

Further continuing the project’s journey, the Menil Collection’s current Sunset exhibition resurrects one largely unseen color film of the sun setting over the Pacific Ocean that Warhol shot nearly 50 years ago for the unrealized de Menil commission. Running 33 minutes (the length of one 1200-foot magazine of 16mm film), this single, unedited static shot is a simple, slow, and imperfect observation of the sun lowering into the horizon and the subtly shifting colors of atmospheric light around it. The soundtrack, added for the film’s inclusion in “****,” features the low voice of German singer/model/actress Nico reciting original poetry (recorded for the film the same year influential albums The Velvet Underground & Nico and Nico’s solo Chelsea Girl were released, and just after her involvement in Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable events).

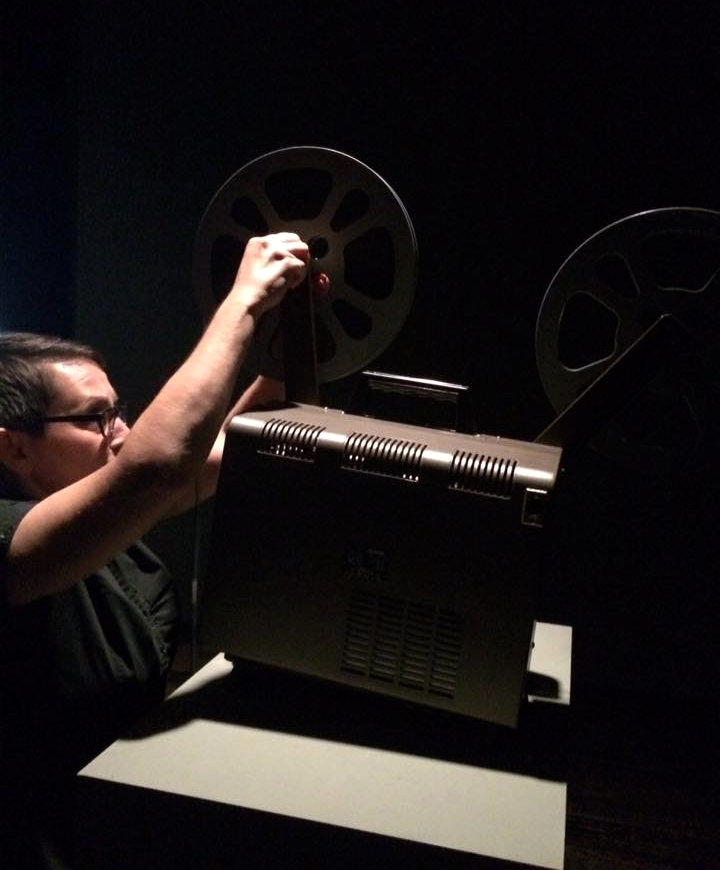

Organizing curator Michelle White could have simply shown a continuously looping video transfer of the film, but she’s admirably arranged a more interesting and appropriately unique presentation. Not only is it being shown in its original analog medium of 16mm film, but it is being screened once daily, at 6 p.m. on every day that the museum is open, for nearly five months. It’s a simple, smart, and bold curatorial decision, nodding to Warhol’s experiments with duration and non-traditional film experience, to the de Menils’ ideas of this work as a meditative experience, and to the nature of the film as an ever-unfinished, ephemeral light work. Sunset’s daily screening adds to the subject’s everyday occurrence a ritual activation of physical medium (film reel), mechanical apparatus (projector), human facilitator (projectionist), colored light (projected photographic image), and, of course, participating viewer. It gives to the work a temporal framing that a looping video would not, with its light-image first materializing from nothingness and finally disappearing completely. And, perhaps most importantly, this extended run of daily showings at a free-admission museum invites one’s changing experiences through repeat visits. (I plan on seeing it multiple times—again with its intended Nico poetry and projector whir and also with headphones and my own music/sound selections.)

Tish Stringer, threading the Sun.

This sort of film exhibition hinges on the collaboration of someone both experienced in handling the delicate medium of film and dedicated enough to commit to its careful projection more than 100 times over many months. Michelle White tapped filmmaker and educator Tish Stringer for the job. I asked Stringer about accepting the responsibility of this unusually long and repetitive projection gig, and she told me “it was just too crazy and perfect to turn down.” Stringer, who grew up in California, fondly remembered beach sunsets shared with friends and family in her youth when committing to the ritual of handling and watching Warhol’s Pacific Ocean sunset film. But it also resonated on many levels with her Houston experience. Her first visit to the Rice University campus in 2000 happened to coincide with the premiere screening there of the recently re-discovered Sunset film, which played a part in convincing her to attend the school. Now, Stringer teaches film at Rice. She works in a department founded by the de Menils, in a building that they commissioned architect Howard Barnstone to design, and 50 feet from a tree that Andy Warhol planted during his 1969 visit. She will be in the gallery to project (and see, and contemplate) a majority of the sunsets over the coming months. While her presence there is, by nature, a quiet and nearly invisible one, you might consider giving her at least a grateful silent smile for her cinematic dedication as you pass.

As much as I’ve gone on here about the origin story and surrounding connections, none of that matters in the experience of it. This show is simply one piece, shown once a day, and this piece isn’t physical, or fixed, or even finished. While it could be considered any or all of these, it’s not Pop or abstract or conceptual or religious art. If one clears the mind, and one should, Sunset is simply the flickering idea of a sunset and one’s own thoughts during the slow, real-time meeting of star and horizon.

On view at the Menil Collection (Houston), from 6:00-6:33ish p.m., Wednesdays through Sundays, through January 8th.