Andy Warhol, John Wayne (from Cowboys and Indians), 1986. Screenprint. Courtesy of Jack and Valerie Guenther. © 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Classic Western shoot-em-ups often featured a handsome marquee star with his flavorful, character-actor sidekick. Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, for instance, were generally teamed with doughy comics like Pat Buttram, Smiley Burnette, and that most lovable grizzled desert sage, George “Gabby” Hayes. With its current double-barrel blast of Western Pop, Andy Warhol: Cowboys and Indians and Billy Schenck: Myth of the West, San Antonio’s Briscoe Western Art Museum revives that formula.

Andy — and yes, the artworld and mainstream American culture are so wedded to the droll and silent cipher with the silver shock faux-mane that we may call him Andy — created his suite of ten prints called Cowboys and Indians in 1986 as part of his “business art” production. The 27 works on view by Santa Fe-based painter Schenck — often called “the Warhol of the West” — date from 1972 to 2017 and serve as a rodeospective of his smokin’ pistol career.

I wore out the grooves of the track “Andy Warhol” on David Bowie’s album Hunky Dory shortly after its release in late 1971. “Andy Warhol looks a scream. Hang him on my wall. Andy Warhol, Silver Screen. Can’t tell them apart at all.” And I think that’s the kind of osmotic process through which many young Americans inhaled the Warholian myth and aesthetic, especially down here in the territorial cactus patch. Intoxicated with visions of soup-can glory, at least one of my friends had already taken to gluing toothpaste tubes on tiny pedestals.

Just like in Bowie’s lyric, we often failed to perceive the “there” that was there. As Warhol’s last major project — according to Briscoe literature — before his 1987 death from complications following gall bladder surgery at the age of 58, the Cowboys and Indians portfolio reminds us of the artist’s important role in popularizing the screen print or serigraph in a fine-art context. When I first started noticing Andy’s Marilyns, Elvises, Jackies, Micks, Maos, Liz Taylors, bananas, flowers, and electric chairs, the medium — because it was drenched with the auto-mindset and tone of advertising — seemed instantly classical.

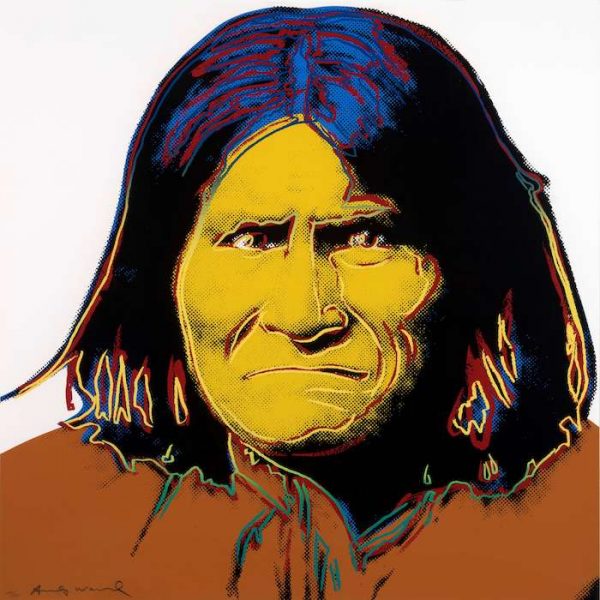

Andy Warhol, Geronimo (from Cowboys and Indians), 1986. Screenprint. Courtesy of Jack and Valerie Guenther. © 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

I’m conflicted on whether the color squish blaze treatment works as well on General Custer, Annie Oakley, Teddy Roosevelt, John Wayne, Geronimo, and the other subjects of Cowboys and Indians. Sure, they’re gorgeous works of art, and there’s the marvy factor in simply oozing, “It’s a Warhol.” But Geronimo was among the most photographed humans on earth when he strode the speck. And many, many images of the inscrutable Apache medicine man wield a power that spooks the dooky out of 1960s popification.

Stalkers of the Warhol oeuvre are interested to learn that Cowboys and Indians was the first and only portfolio in which he printed more images than those selected for the final edition. Four trial proofs are presented in the Briscoe iteration, including Buffalo Nickel, Action Picture, and Sitting Bull with a blue face. It was also the only Andy print series to combine portraits with images of material culture, such as Kachina Dolls, Plains Indian Shield, and Northwest Coast Mask. Vivid and lively to behold as they are, I’m still wondering how the work “explains the myth of the American West and American nostalgia for the Old West” beyond the mere fact of its existence.

Andy Warhol, Annie Oakley (from Cowboys and Indians), 1986. Screenprint. © 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

There’s also a tendency to over-read socio-historico construction-deconstruction in the title. But I like to think it could also be considered in the context of the artist’s widely-noted childlike characteristics. I don’t know if little Andy actually played Cowboys and Indians on distant Pittsburgh afternoons, but considering the brilliantly boring accumulation and documentation of lived minutiae in his diaries and films, one can easily picture him watching other kids do so with the same sly expression he evinced in The Factory, photographing the scenes with his tender imagination and storing them for future apps. In fact, so much detail and fascinating, sometimes useless data piled up in his streaking arc on the planet that I confessed to Fort Worth artist William Williams that I felt kind of an out-of-body horizontal freefall across a vast desert of cactus patch while harvesting info on Our Andy of the West.

“What’s interesting about Warhol to me, for all the seeming nihilism, are the religious underpinnings to his life and personality,” countered Williams. “The extremely presentational and straightforward nature of his work is really based on Eastern Orthodox iconography.” Pressed on this statement, Williams directed me to an article distributed by the Catholic News Agency in 2015:

“If I had to describe Andy Warhol’s work in just one or two sentences,” art historian James Romaine noted in the article, “I would describe it as the world seen not as it is, but the world seen as it might be transformed by grace.” The artist, Romaine asserted, was “striving for grace in a broken world.” As an example, he pointed to the artistic transformation of the famous soup cans; Warhol “removed them from a time and place context in which they’re disposable, into a timeless realm in which they’re almost like icons.”

The artist’s nephew Daniel Warhola, who retains the original spelling of the family surname, commented on Uncle Andy’s shape-shifting trickster persona creation. It was almost “like he could see himself as a work of art, and let you create the narrative.” Elsewhere, a more secular observer, biographer Wayne Kostenbaum, echoed Romaine. “When I look at Warhol,” he wrote, “what I feel is maximum redemption of lost material. He puts meaning back where there was deadness.”

Though not included in the Briscoe show, Billy Schenck’s prolific output includes the painting Nixon Accuses Warhol, with these words bannered at the top like comic book narrative: “RICHARD NIXON ACCUSED WARHOL OF BEING SPIRITUALLY DAMAGED.” Born in 1947, Schenck discovered Lichtenstein and Warhol while in art school and during a spring break even worked as a volunteer with the multimedia show Exploding Plastic Inevitable that Warhol conjured to complement the Velvet Underground. In another important art-school epiphany, Schenck slurped his first spaghetti western.

Both the Hollywood and Italian versions of the horse opera influenced Schenck’s early, promo photo-based works in which he traced outlines of movie stills on a canvas and then filled in the color with a paint-by-numbers-style technique. Briscoe examples include Carbon County Vigilantes from 1972, and John Wayne leading troops through what appears to be Monument Valley in Patrol from Yuma, from 1973. Another influence was the campy sagebrush graphics of vintage Western pulp fiction.

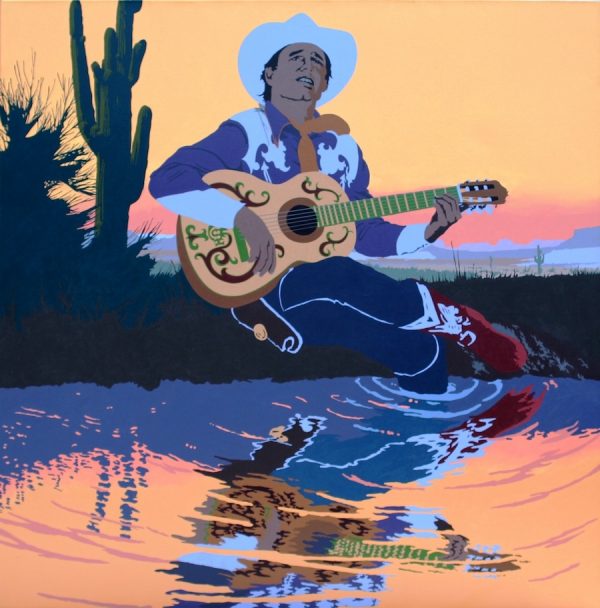

In the ’80s, Schenck began adding narrative content with captions and recurring characters. In the Briscoe show’s 1990 oil painting, Blazing Saddle Horns, a Warholish, Marilynesque figure in a checked shirt on horseback says in a thought bubble, “OH BLAZING SADDLE HORNS! IF I LOOK INTO CLIFF’S DEEP BEAUTIFUL BLUE EYES AGAIN EVEN MY PISTOLS WILL MELT DOWN!” In the 1986 oil on canvas, A Singing Cowboy’s Hero Sunset, a world-weary dude with guitar, rocking Opry duds, sits in a wash of fading light with Schenck’s characteristic tertiary hues and pastel shades.

Schenck’s collision of contemporary culture with symbols of Western tradition is exemplified here in a 1985 screen print, Anything Can Happen in the Afternoon. The glamorous lady in a cowboy hat and movie-star shades evinces such attitude that we think she’s about to blow cigarette smoke in museum-goers’ faces.

In an interview, the artist recalled the profound effect of a family visit to the sky city of Acoma Pueblo when he was only five years old. On top of a mesa, he saw Indians dressed in white blankets and buildings made of adobe. “That was my first real connection to the desert, and it never left me.” His work changed again with a move to Santa Fe in the 1990s. Discovering Herbert Dunton and the Taos Society of Artists (1915-1927), Schenck concentrated on exploring, photographing, and painting Pueblo life, Native American rodeos, Navajo horse culture, and southwestern landscapes.

The lady on horseback in the 2012 oil painting Many, Many Miles echoes the Native woman gazing vast distances on the Northern Plains in Charles Russell’s 1911 oil In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners. Other Briscoe show works from this period, with which I was especially taken, include the 2009 serigraph Deep Into the Desert and the 2014 oil painting The Mighty Mesa. A 2016 oil on canvas, The Last Sunset, demonstrates that Schenck continues romanticizing the West even as he laments its passing.

With his boots on the ground under Western suns, it’s clear from his work that Schenck has soaked up more of the big-sky psyche than the fella called Drella. But it’s also undeniable that, just as there “might not have been a Merle or a Willie without a Django and a Jimmie,” there wouldn’t have been a Billy if there hadn’t been an Andy. “There is no way,” Dave Hickey once expounded, “that anybody who is much younger than I am can understand how profoundly different the world before Andy and after Andy looked… . He literally changed the way the world looked.” And even in the big fat West, that’s a damn big deal.

‘Andy Warhol: Cowboys and Indians’ and ‘Billy Schenck: Myth of the West’ are on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio through September 3, 2018. Note: Some of Warhol’s ‘Cowboys and Indians’ pieces can also be seen at The Bryan Museum in Galveston. The entire suite appeared at the Longview Museum of Fine Arts earlier this year.

1 comment

Great review! If I head points east within the next four weeks, I will make a true attempt to visit the Briscoe and view these exhibitions.