I recently traded the gritty Houston humidity for the strange sibling rivalry of the Dallas/Fort Worth area. Somewhere in the center of this familial spat is the University of Texas at Arlington. It was here that I met Jeff Gibbons and Justin Ginsberg. As part of their collaborative project called Apophenia Underground, the two have put together a string of “pop up” style exhibitions on Main Street in the Deep Ellum area of Dallas, aptly called Deep Ellum Windows.

From what I have been able to gather from their enigmatic rhetoric, Apophenia Undergound intends to use objects as totems linking places, events and ideas. Stumbling through the nebulous network of web links on their site, I ended up with a plethora of error messages, images of past Deep Ellum Windows shows, a low-res image of a Wikipedia page on the Olmec people, some artist sites, a video of something being buried and a few delightful dead ends. This deliberate and cryptic open-endedness gives the two artists an amorphous starting point. It keeps them from getting locked into any singular trajectory or self-fulfilling artist’s statement, and leaves them at liberty to change direction at will and employ a varied group of creative tactics.

During the Dallas Art Fair these two guys had three spaces open simultaneously. The first, at 2625 Main Street, was Kristin Oppenheim’s She Was Long Gone. This was a group venture between Apophenia Underground, Oliver Francis Gallery and 303 Gallery in New York. The second was Perishabel at 2646 Main, a show featuring work by Luis Miguel Bendaña, Nick DeMarco and Pierre Krause, curated by Oliver Francis Gallery founder Kevin Ruben Jacobs. Thirdly, at 2650B Main Street, is Hannah Hudson’s Compliance, curated by Apophenia Underground. I am going to focus on Pierre Krause’s work in the second room of the Perishabel show and Hannah Hudson’s exhibition.

Krause’s light touch seems to be the only real answer to the old machine shop she’s working in. As you enter the back area of the Perishabel show two things greet you: a large piece of machinery and the color blue. The bright plastic blues against the smooth grey concrete floor contend well with the hulking remnants of a vertical lathe that all but overwhelms the space. Its looming presence recalls an analog age where Krause’s cast plastic objects and containers would seem strange—toxic even.

Krause’s placement of readymade, found, purchased or whatever objects in a building that once was a shrine to precise and specialized manufacturing juxtaposes two distinct stages in the history of industry. The steel and aluminum parts turned on the lathe were machined from those materials for their hardness and resistance to friction and heat; by contrast, Krause’s objects are in various moldable, elastic plastics. One type of material is used for its constancy and resistance to change: The fact that the machinery is still in the space is evidence of the aesthetic of permanence. The other type is exactly the opposite, chosen for its ability to move and change. The opposition between these materials is palpable, they almost shout at each other from across time.

In a city like Dallas, with its penchant for decadence, it’s nice to see the understated done so well. Several small decisions contribute to this. The first is the uniform color of Krause’s installed objects; the color continuity carried across a varied group of things kept me from immediately going over to the lathe. There’s everything from blue windshield wiper fluid to a blue plastic bag to a blue yoga mat. It is as if she color-corrected the air in the room. Another great moment is the cord on the small TV, stretched taught from a wall outlet, putting the TV as close as possible to text on the floor that reads “get your head in the game.” Paired with the TV, it could call to mind some tenuous association with sports or how TVs make you stupid, but I hope that’s not the point.

Hannah Hudson’s Compliance at 2650B Main Street speaks to the space it inhabits with a similar subtlety. The show is in a dusty space that shares a door with a tattoo shop and bears the scars of previous tenants’ odd color choices. When you come through the door you aren’t greeted by anything overtly out of place. Hudson’s, like Krause’s, is an understated approach. Everything in the space seems like it could have been left there, down to the clamp lights used to spotlight specific areas.

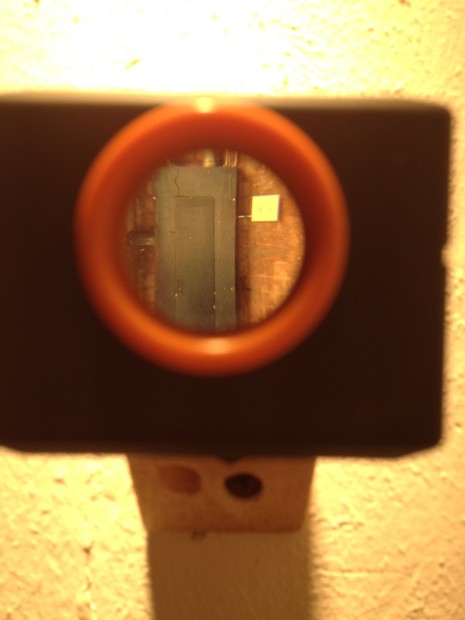

The work consists of peepholes peppered throughout the space that reveal snapshots of interesting moments of the building housing them. One peephole in particular housed an image of the electrical breaker box with various parts of the building’s network cascading out from it. Generally this is an aspect of a building I might just accept as utility and move on, but Hudson’s lens creates a small interior space that gives the commonplace added consideration. I was struck by my own laziness—it took Hudson’s mediation for me to notice some of the unique qualities of the space. I imagine a large number of tourists experience the majority of their vacation through the viewfinder on a camera. At the risk of hijacking Hudson’s work, I thought of the way friends and family seem to seek validation for their daily goings-on by presenting photos of their lunches. Maybe a pervasive over-reliance on lens-based media is Hudson’s larger point?

In a cityscape where seemingly no surface is passive, saying more with so much less is a real skill. This batch of Deep Ellum Windows artists are doing just that.

2 comments

Great article! Loved it.

Thanks Mom.