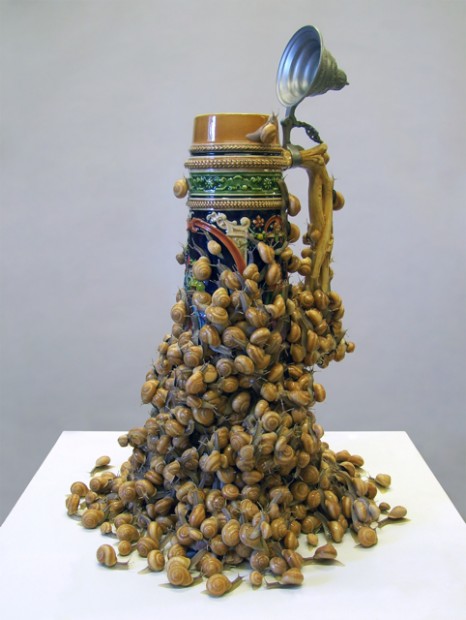

Before I entered the gallery to see Erick Swenson’s Sightings at the Nasher, a guard politely stopped me at the door and warned me that there was work in the space that was a bit grotesque and perhaps not for the faint of heart. I thanked her, told her I was prepared to face the music and went into the room. A bevy of uniform-clad school girls were there already, squealing and feigning nausea at the two pieces in the front of the space. The first was an enormous beer stein covered in a swarm of life-like, slimy, creeping snails and the second, a conch shell filled to the point of rupture with a muscular-looking mass of unidentifiable, puce-colored flesh. Though I certainly wasn’t about to join in, the school girls’ squeals were warranted—the work is repulsive. But, like all of Swenson’s work, that repulsion is part of why it’s beautiful—the power he manages to harness so subtly through the use of quantity, absurdity or ambiguity, to say nothing of the painstaking perfection of the objects’ manufacture, triggers nothing short of awe.

The pieces in the first gallery, called Schwärmerei (which loosely translates to “superficial enthusiasm”) and Scuttle, respectively, each employ a vessel—the stein and the shell. The snails appear to make a slow-paced though zealous race toward the mouth of the uncapped stein, which promises something in its well—meanwhile, the brimming mass of the flesh-creature seems poised to burst through the shell it occupies. The action in each registers as a kind of takeover—the snails overrunning the beer stein, the muscle mass/creature consuming what was inside of, or itself outgrowing, the conch shell. Both images suggest self-destruction: the beer ostensibly contained in the stein is a notorious snail killer, and the title Scuttle references a nautical term referring to the sinking of one’s own ship.

The sense of repulsion we feel with these objects might be about what they look like—slimy, gelatinous things—but these creatures’ implied actions can also be seen as metaphors of power. That Swenson uses these repellent creatures to enact doomed sieges is provocative, suggesting the various power paradigms that exist in society at large. (I thought about the work in the context of art world politics—collectors and artists, dealers and artists, the art market and art commodity and all the tangled webs of interior and external loathing that populates the artist’s psychological life.) But everything is secondary to the primal experience of looking at these two works, an experience which has everything to do with nature’s power over our nervous system. And even though these pieces work a good deal harder than that, that’s enough.

Around the wall that flanks the front space of Swenson’s show is a low-lying floor pedestal where a deer carcass, made of acrylic on urethane resin, lies in a state of decay. Nearly all of its bones are exposed, its mouth agape, its antlers clinging to a bare skull. Turning the corner and seeing the piece, called Ne Plus Ultra, elicits a gasp, just as seeing the figure in its open-air grave in the wild would, though the contrast of the decomposing body against its white platter is stark, exaggerating the true-to-life details of rotted flesh and organs. And here in the museum, in a low-lit gallery on a clean white slab, without the flies and insects that would cover it in nature, the carcass feels like a pure specimen, like a butterfly tacked to a velvet board. A close inspection of the animal reveals tiny, intricate maps etched into all its bones, making the creature shamanistic, as if the world’s previously uncharted places were written in its body, untapped secrets revealed in death. The carcass is a long-sought treasure, as enigmatic and delicate as it would have been in the wilderness, once teasing and then eluding its pursuers, now stilled.

Swenson has managed, in this body of work, to both tame and let loose nature’s most poetic utterances.

Sightings: Erick Swenson

Nasher Sculpture Center

Through September 9, 2012

____________________

Lucia Simek is an artist and writer based in Dallas. She and her husband, Peter Simek, founded the much-loved, short-lived arts and culture site Renegade Bus in 2009. She has also written for THE Magazine and People Newspapers, and is currently a frequent contributor to D Magazine‘s arts blog, FrontRow. She also acts as the arts commentator for the kids blog Tiny Dallas.