Author’s Note: This is the fourth in a series of articles that recounts my experiences as a Fulbright Scholar in India. I recently returned from the first of three trips. I spent a month in Ahmedabad/Gandhinager, three weeks in Kolkata, and my last week in Goa.

I spent three weeks in Kolkata, India this past October during the frenzied Durga Puja season. Despite Durga Puja’s designation as the largest global public art festival, it’s surprisingly unknown in most of the world. In speaking with those involved with the festival, I heard it referenced as being “bigger than Rio” (presumably the Carnival in Rio de Janeiro). There are aspects of the event that reminded me of the Venice Biennale, such as the site specificity and emphasis on socially engaged themes. There’s also a bit of Vegas spectacle with the light and sound displays, as well as immersive environments with a narrative (think Meow Wolf in the U.S., but outside, in community neighborhoods). I haven’t been to Rio, but assume the comparison has to do with the spectacle, performances, large crowds, and a party-like atmosphere. None of these are adequate comparisons, however, as Durga Puja is a unique entity. Being recognized by UNESCO as a world intangible heritage event underscores Durga Puja’s cultural and historical significance: celebrating traditional rituals, contemporary artistic expression, and community spirit.

Before I describe the experience of pandal-hopping, it’s important to give a brief background on the story of Durga. She is a female Hindu Goddess, and I think of her as a badass warrior who slayed demons, and thus ensured good triumphed over evil. Contradictory mythology surrounds Durga. Some view her as a symbol of female empowerment, a modern-day superhero. Another reading says that she was created by male gods and when she became too powerful, she was domesticated. As a feminist this is not my favorite viewpoint, but it does align with the views many world religions have about women.

I took over 200 photographs during my visits to the various pandals (installations). Due to the scale of the work, it’s difficult to get a sense of the nuances within each architectural structure. Each pandal is sponsored by a community club located within a specific neighborhood, and includes a prominent Durga altar. Imagine a dense urban city with myriad of neighborhoods containing winding, narrow streets and alleyways. Just when you think the GPS or taxi driver has taken you on a wild goose chase, you find yourself awestruck by an architectural wonder. As I traveled from pandal to pandal, I felt like I was on a treasure hunt. The pandals come alive at night; it is a magical experience.

Artists and artisans work for months creating the massive art installations, then disassemble them after the two-week festival. The event itself is a festive holiday, important enough that it closes schools and businesses. Kids look forward to staying up all night pandal hopping with their friends and families.

The term “community” is bantered about a lot in contemporary art, especially in art that is deemed “social practice.” Here, I really witnessed communities coming together to create the pandals. The involvement of community members in various aspects, beyond just financial contributions, speaks to a deep sense of collective participation and shared responsibility. Despite differences in caste, class and religion, there was a sense of community pride. One phrase I heard over and over again throughout my visit was that all are welcome. Transcending societal divisions, this mantra reinforced the idea that art has the power to affect change and manifest communal strength.

And now for a photo essay of my pandal hopping experiences.

****

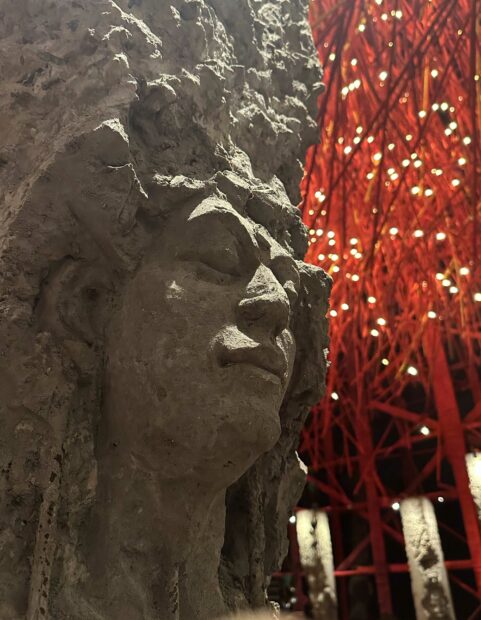

An in-progress shot of Rintu Das’s “Don’t Want To Be Uma,” Kashi Bose Lane Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

In this installation, located in the Red Light District of Kolkata, Das brings awareness to the sex trafficking of women and children. I visited some of the pandals the week before previews and had the pleasure of seeing the works in-progress, which made the transformation of the festival even more remarkable.

“Uma” is another word for “Durga” and references how the exploitation of women is an affront to Durga, who symbolizes divine feminine power.

The hand covering the mouth is a repetitive motif throughout the installation, symbolizing the fear and silencing of women and children.

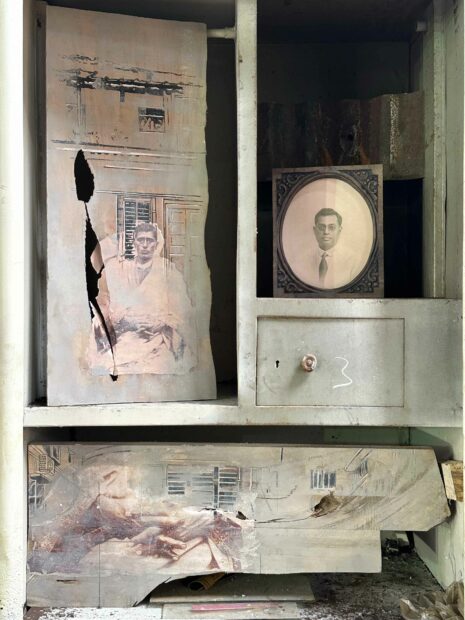

Pradip Das, “Heart-land:Montage of Memories” (Exterior detail), Naktala Udayan Sangha Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

The work explores the lives of the residents of Naktala, which was the first refugee colony to be recognized by the government after Partition in 1949. The architectural structure made from salvaged materials references makeshift communities.

Pradip Das, “Heart-land:Montage of Memories” (detail), Naktala Udayan Sangha Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

In the years leading up to the event, Das collaborated with residents of the neighborhood, interviewing them about their experiences with forced migration from East to West Bengal and their struggles to form new communities and identities. The salvaged wardrobes reveal family images distressed by time, symbolizing resilience.

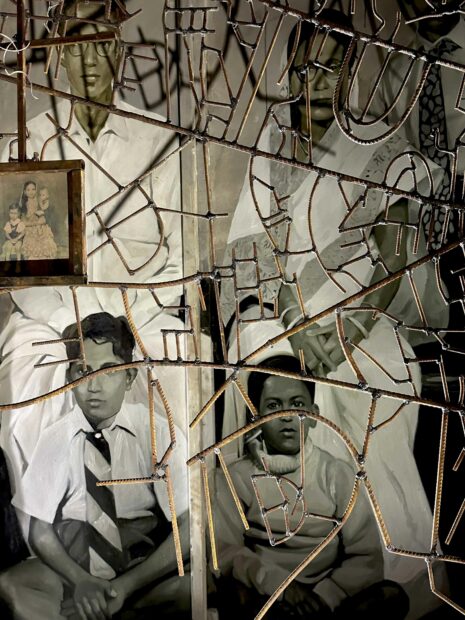

Pradip Das, “Heart-land:Montage of Memories” (detail), Naktala Udayan Sangha Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

The community donated family photographs and personal artifacts to include in the installation. The metal sculptural detail references maps of original and current neighborhoods, as well symbolizes physical and political barriers—who is kept in and who is kept out.

Bhabatosh Sutar, “Divinity of the People,” Durga Alter, Arjunpur Amra Sabai Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

Typically sculpted with ten arms, Sutar’s Durga instead has two arms, representing humanity, with her other eight severed from her body and reaching towards the sky. I originally interpreted these as imprisoned or dead victims from the Manipur Genocide. But upon looking closer, I noticed that their wrists were not bound with rope, as I initially thought, but covered in bangles. The gesture is one of solidarity and hope.

Bhabatosh Sutar, “Divinity of the People,” Exterior, Arjunpur Amra Sabai Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

As Sutar began construction, news of the Manipur Genocide surfaced. His work is a call to action of freedom from violence and oppression.

Exploring themes of creation and destruction, this work points to perpetual violence in the name of religion, hatred, and power. The doves form a halo above the head, symbolizing hope for the future.

Stone columns with carved faces lined the interior of the installation. I interpreted this as evidence of the creation following destruction.

Pradip Das, “Stories of Unseen Rebels,” Exterior, Dum Dum Tarun Dal Club, Durga Puja, Kolkata, 2023.

Das’ work pays tribute to Indian female freedom fighters who did not make it into the history books.

Interweaving history with personal stories, this work features light boxes with photos of the women revolutionaries, adding faces to the historical text.

This was one of the few pandals I attended that focused on folklore and included puppetry. At the entrance was a traditional puppet show. The interior structure impressed me with its level of artistry. Master weavers created a plethora of woven textures. Durga is presented as a large marionette with one human on each side, moving her many arms.

The pandal is an imposing and impressive architectural structure. It was the largest pandal I visited, and I was struck by the care that went into the lighting details. Beautiful, reflected shadows adorned the exterior and interior spaces.

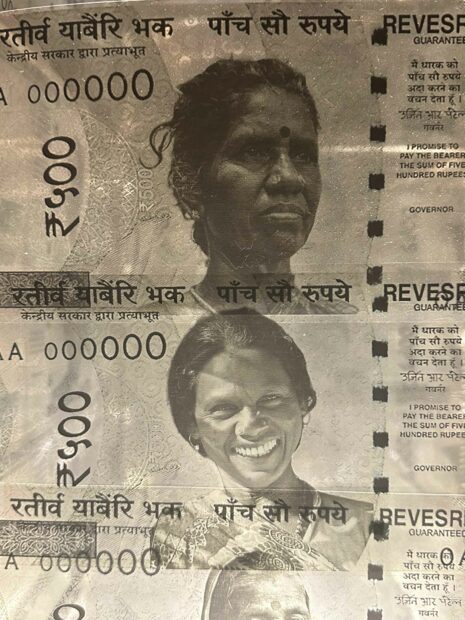

Using advertising banners juxtaposed with carnivalesque atmosphere, Paul’s work addressed the consumption and consumerism of Durga Puja.

Printing the faces of laborers on money, Paul points to the hidden labor behind the construction of pujas.

Das’ work explores the relationship between nature and humanity.

Located next to a small lake, the boat structures reference people’s reliance on water for survival.

The magical interior features light rain falling from the ceiling into a pond. Channeling and recycling the water from a local lake, the work points to water’s significance as a precious commodity. The piece highlights the fact that over 70% of India’s water is contaminated, causing illness.