I read in a recent edition of the Brooklyn Rail (in Eileen Tabios’ poem “The Road to Juliana”) that the cornea of the eye has no supply of blood, and instead draws oxygen directly from the air. This suggests an exceptional adaptation, as all other systems of the body rely on a robust vascular network to be oxygenated. This absence of blood vessels is crucial for maintaining the cornea’s transparency, which is essential for clear vision. Seeing is how many of us navigate the world, perceive time, go from start to finish. Visual art too is almost completely dependent on sight.

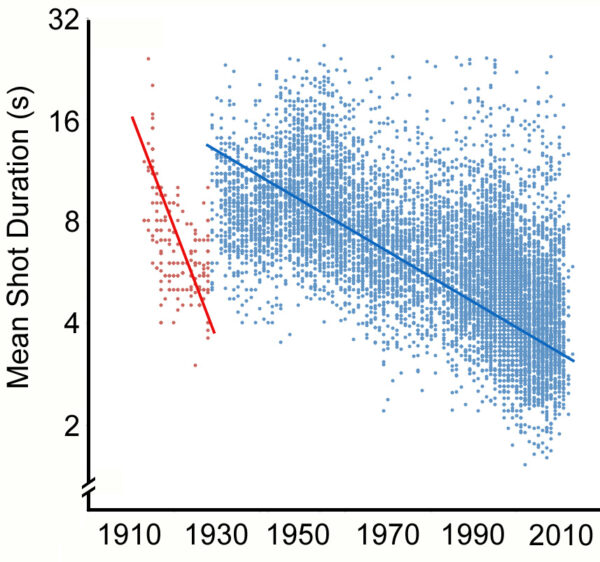

Consider film as a medium. In a 2010 study, scientists at Cornell University claimed that the average shot length in cinema has decreased significantly since 1910. Regardless of whether this is due to the preferences of audiences or film directors, it suggests that human attention is progressing in the direction of brevity. When I evaluate a work of art in terms of drawing, I think of the distance between two points. Film is viewed in linear time. A long film with more cuts still draws a long distance. In the Cornell study, the thesis is that the duration of the cuts has decreased with time, meaning more points are created within a given film’s runtime.

The average shot length in English language films has been declining, according to research by James Cutting. Graphic via the Cornell University Department of Psychology.

While laundering my clothes at an artist friend’s apartment (my dryer was on the fritz), I decided to use her vast repertoire of markers to doodle. I am out of my home quite frequently, which has limited my ability to hold down a studio practice. Viewing art regularly has given me an appreciation for seeing, but making art stirs the brain in a different way. Stopping, for a moment, to pick up a pen or marker, has become novel again, and sometimes it helps me work through a task if I feel like I’m stuck. Like film, drawing has the capability of pushing one forward in time. Although I possess some ability to render realism and to sketch from life, I am usually more motivated to improvise, at least in part because I’m easily frustrated by my inability to perfectly capture what’s in front of me.

Aside from making me feel more creative (when the exercise is successful), drawing also teaches me how to “see” texture, dimension, and form. Even when viewing works by the masters, as in the Dallas Museum of Art’s 2023 exhibition Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools, which showcased centuries of Flemish still life painting, one can see that a successful rendering still requires tricks of the eye. Looking at drawings will teach you that paradoxically: illusion is the key to recreating something faithfully.

A prominent Dallas painter once told me his favorite painter was Quentin Tarantino. After that, I began to realize how intertwined the different mediums of art are. However, when examining artwork, I find myself starting from the question, “Is this drawing?” Drawing takes two points and articulates a definite path between them. This is similar to geometry, where points are discrete locations in space, and lines are the exact distance between them. Painting is then, instead, the creation of imagery through the mastery of material. In painting, the mark being made in the image can be almost anything. In drawing, a mark is almost always a line.

The doodles I produced while waiting for my laundry to finish took on a consistent form. During this particular drawing session, I realized I was organizing my scribbles into eyeballs. Over and over, I fiddled my markers into globes with a central oculus. Some contained more dimension, while others remained flat and embraced the bold lines of an illustration. It is fascinating how easily an illusion can be created with a few lines.

William Sarradet is the Assistant Editor for Glasstire.