Earlier this month, Bale Creek Allen Gallery opened a new exhibition by Terry Allen, the Lubbock-raised, Santa Fe-based musician and artist who is also Bale’s father. This show doesn’t come out of the blue: the first time Bale presented the elder Allen’s works was in the late 90s at his Gallery 68 in Austin. Since opening BCA Gallery in 2016 (first in Austin and now in Fort Worth), Bale has always kept a few pieces by his father on hand for collectors and clients to see, but until recently he hadn’t exhibited the work. And while last summer Allen was included in a group show featuring James Surls, Billy Copley, Shelli Tollman, Will Squibb, and Daniel Johnston, the current exhibition is the first time the gallery, in its current iteration, has presented a solo show of Allen’s work.

Over the last few years, Allen’s work has been shown in cities across Texas. In early 2022, Down in the Dirt: The Graphic Art of Terry Allen was presented at the Museum of Texas Tech in Lubbock. Around the same time, The Blanton Museum of Art in Austin debuted Terry Allen: MemWars, featuring works on paper and a video installation.

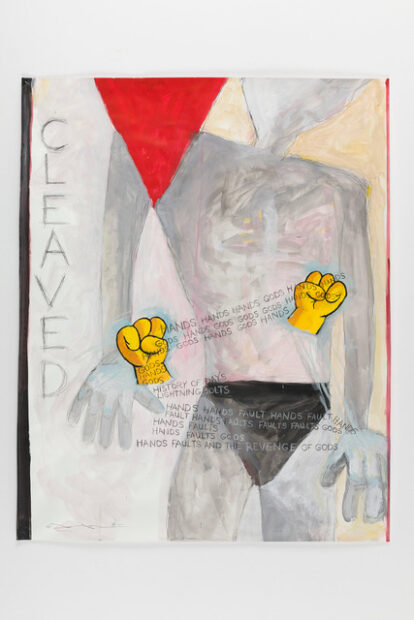

The exhibition at BCA Gallery, Homer’s Notebook II, features a series of gouaches created by Allen from 2017 to 2019. Originally shown in Los Angeles at LA Louver as part of The Exact Moment It Happens in the West: Stories, Pictures, and Songs from the ‘60s ‘til Now, a retrospective of Allen’s work, the series juxtaposes imagery related to Homer’s epic Greek poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, with references to Homer Simpson. Recently, I spoke with Allen about this body of work, his interest in storytelling, and how he approaches new materials.

Jessica Fuentes (JF): Your series references the Iliad and Odyssey — why these stories in particular?

Terry Allen (TA): Well, I was reading both of those books and I was always taken with how elegant the murder stories and that kind of butchery was in them, especially the Iliad. And another thing was the idea that Homer was blind, supposedly, and then how incredibly vivid visually the book is. But anyways, I think Homer Simpson came as a counter to those two worlds… the Iliad being so sophisticated and presented on such a high standard and then Homer, just kind of down there where the rest of us are. So, I wanted to make something that presented that.

JF: It’s an interesting juxtaposition. When I think about Homer Simpson, I think about all the things he is blind to as well.

TA: Exactly. You know, there are funny situations, like Ulysses’ dog, Argos, who diligently waited for him for twenty-something years, and then as soon as he reappeared, died. There’s a drawing of that dog, but right above it is Homer’s dog, whose name is Santa’s Little Helper… so there are those kinds of contradictions throughout the whole piece. And then, I got interested in words like “cleaved” and “rendered.” Just the formality of talking about somebody having their body hacked on, using words like cleaved and rendered and darkness flying across his eyes like a bird… that kind of poetry is very beautiful, but what it’s talking about is totally horrendous.

JF: I think you captured that kind of juxtaposition really well in the pieces, because you have this kind of abstract approach to the breaking of the body and there’s a beauty to it, but there’s also this terrible violence taking place.

So, as you were reading, how did you come upon these words in particular? Were you taking notes as you were reading, or did they stick in your mind and you came back to them later? What was that process like?

TA: When I was reading, I wrote a [Homer’s] Notebook I… I was reading some Sam Sheppard pieces, some Christopher Logue — different people whose work was kind of around the idea of the Iliad… so I just kind of started writing ideas down. I was sitting at the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles in San Antonio and I was sitting next to this old guy, who really didn’t say a word until all of a sudden he elbowed me and said, “You know, I was born dead…. Yeah I was born out on the flats on a cold night and the doctor was a quack because I was born blue and wasn’t breathing and he said I was dead and he left. And there was a woman who was a veterinarian and she said, ‘No, he’s not dead, put him in the oven.’” He went on to claim that they lit the oven and put him in the oven, and she went out and got a bucket of ice water and pulled his little steaming smoky body out and dumped him head first into the bucket of ice, and he said, “I screamed myself into life.”

So, it was stories like that that kind of combined the hilarity of one thing, but also the horrendous image of it… these stories kind of popped up all through those notes I was taking, things I was writing, along with ideas about the Iliad and the Odyssey.

JF: I’m interested in the way you and your art are inspired and informed by this literary work. As a person who is a collector of stories, can you talk a little more broadly about how stories influence your work and shape what you do as both an artist and musician?

TA: Well, I grew up around storytellers; both of my folks told these elaborate stories about their lives. They were quite a bit older — my dad was 60 when I was born and my mother was 40. I was an only child. My mother was a professional piano player and my dad had been a professional baseball player… so I grew up hearing endless lies and tales about baseball and about music. So, I came out of that kind of a culture and I think when I went to art school I collided with Abstract Expressionism, which I had a very difficult time justifying meant something to me. I started dealing with stories and narrative ideas and also playing music and writing songs… it just seemed like a natural kind of progression for me to make stories. That’s what I’ve always been most interested in.

I’ve never been prejudiced about any materials or ideas particularly that would come in… whatever idea I have or that I get interested in dictates pretty much what materials I’ll use or how I am going to investigate it.

JF: Yeah, you don’t let the materials guide you. You let the narratives and the ideas guide you.

TA: Yeah, I don’t think it’s about materials.

Terry Allen, “Corporate Head,” 1990, bronze. Citi-Corps Plaza “Poets Walk,” Downtown Associates, Los Angeles, California.

JF: So, how do you explore new materials? If you are drawn to something you haven’t used much or don’t have much experience with, how do you go about working with something new?

TA: I think it relates to opportunity… like in the early 90s, when I was invited to do a piece at the Citi-Corps Plaza in LA, and I had an idea to do a bronze. I had never thought about doing bronze in my life, but because I had this particular idea, I went to a foundry and I started working and I got really interested in making bronzes, which I still do off and on now. But I think it’s those kinds of circumstances.

I also was invited… in the early 80s [to do an outdoor work for] The Stuart Collection. I was always very resistant up until that time to outdoor sculpture, because I always thought of it as “plop art” that was thrown in front of some corporation to show how rich they were. So, it took me about five years of going back and forth to the site to come up with an idea of something that I wanted to do. I ended up doing these three trees, covered with sheet metal, which have sound systems in two of them. I invited musicians to write songs that they’d like people to hear coming out of a tree, and I invited poets and writers to do stories and poems coming out of the other tree. Then the third tree is like a table of contents — engraved in the lead are all of the people who were involved in both of the other trees, as well as the people who helped me fabricate everything. This project really turned around my idea of the possibility of working at specific sites, and I kind of got over that naivety about what a public artwork could be.

So, I think it’s a growing process… it always has been for me. When an opportunity presents itself and you get curious about the necessity of making something, then you kind of gravitate to whatever you think you need.

Terry Allen, “Trees,” 1986. The Stuart Collection, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California

JF: So, for Homer’s Notebook, one question that I still had on my mind was: did you have music in mind with this body of work, either something you were listening to or something you were conceiving, while you were creating the series?

TA: You know, I really didn’t think much about music. I thought a lot about sounds… a lot of clanking and yelling and wind. I think with everything I’ve ever done, it usually has a lot of wind… coming from West Texas or Lubbock. I think you always… have more than one sense available, you always have the opportunity to make songs or make sounds when you’re making anything… you make actions. I think that because these stories are so theatrical… you think a lot about actions and how things might be staged.

JF: This series was completed in 2019; what are you working on now?

TA: We’re working on a family album. The whole family is getting together and writing songs. We’ve recorded about 11 songs so far, and we’re trying to get that finished by the end of the year.

JF: That’s really exciting. How long has that project been underway?

TA: Oh, since the kids were born… Yeah, it’s been really good. It’s like, a clutch of just very tender songs, and our family band is called Blood Sucking Maniacs… so you have another one of those contradictions. We’re trying to get it all recorded and laid down by the end of the year… but one of the problems is that it’s like herding cockroaches, because everybody is off in different directions at all times. So getting under the same roof is a monumental task… we don’t have a deadline, we’re just trying to get as much good stuff down as we can.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Update November 20, 2023: This article has been updated to reflect that Terry Allen was raised, but not born, in Lubbock.

1 comment

It’s always informative to read Terry Allen’s observations about his work. A slight correction to the introduction of this interview…Allen was not born in Lubbock, not even born in Texas. He was born in Wichita, Kansas.