Last weekend Terry Allen performed songs from his recently reissued 1979 double album Lubbock (On Everything) and his first record, 1975’s Juarez at the Heights Theatre in Houston. If you’ve been wondering where to find the American Dream these days, you’ll find it in the music and art of Terry Allen. You’ll laugh and cry, but there’s no guarantee that you’ll be comforted by what you see and hear.

If an artist is lucky he manages to elevate the stories of his clan into something that no longer relies on the particulars of his life—his people’s tall tales take on the expansive form of archetype and become animated through mythological dreams that are as old as civilization itself. And if that artist lives in America, that dream is the American Dream. The thing about dreams is that they’re never quite normal. In the American Dream, as in all dreams, things are amiss. Nations are perpetually in danger of slipping on that bloody puddle in the greasy center of their mythology and plunging, dizzy and disillusioned, into a nightmare.

In Terry Allen’s world, late-night Lone Star-fueled joyrides down North Texas farm roads and small-time criminal escapades take on the power and significance of every great voyage, every triumph, and every retreat and defeat in the history of American civilization. As far as dreams go, Juarez and Lubbock are a long way down the road toward nightmare, saved only by that famous Yankee impulse toward laughter in the face of horror. But if this all sounds a little too heavy, the ancient human stories in Lubbock and Juarez ride easy on the dark wit and sharp irony embedded in the fine-tuned instrument of Allen’s nasal-pitched voice. Allen makes catastrophe sound funny, and because of that we feel like we might be able to bear it all a little longer.

****

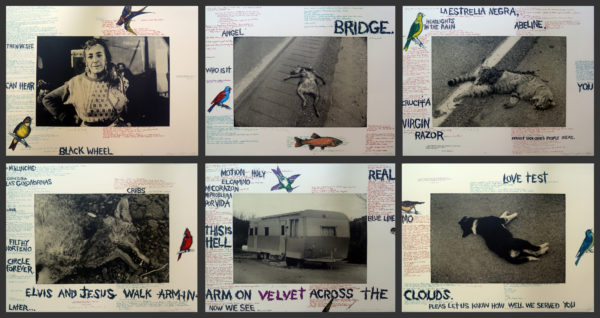

Juarez is pure mythology. Allen reveals the plot—gives away the mechanics of the story—before the record even begins, signaling that the tale of Juarez is larger than the fate of any single individual around whom its violent, sex-soaked plot swirls.

The record’s narrative hinges on two couples: Sailor and Alice and Jabo and Chic. Even though these characters have rough individual outlines—Sailor is a Texas Navy boy on leave from the Pacific front, Alice is a Mexican prostitute in Tijuana; Jabo is a Mexican gang member and Chic is Jabo’s LA girlfriend—Dave Hickey points out in his essay on Allen for his retrospective catalogue published by UT Press in 2010 that the two couples aren’t exactly individuals. They’re more like ideas or social categories. Hickey suggests that Sailor and Alice might represent the American psyche as forged through the experiences of the 1940s and ’50s; an experience that, despite a half century of war and a fragile peace held hostage to the atomic bomb, remained psychologically innocent of the ocean of blood under the long lanes of blacktop.

Through Jabo and Chic, Hickey visualizes what he describes as an America of the ’60s and ’70s that is “recklessly aggressive, articulate” and made hungry by “cynical appetites and a proclivity for mystical violence.” When Jabo and Chic leave Sailor and Alice dead on the floor of a trailer, a transformation, or maybe a mutation of the American Dream takes place. The sticky moral ground of Vietnam and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and John and Robert Kennedy would come to characterize the new America that comes to full-throated form in Allen’s music, drawing and sculpture.

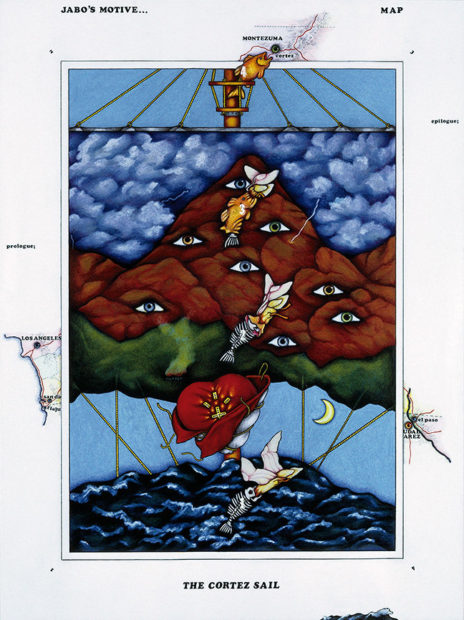

The sprawling tale of Juarez begins by leaping back in time. Cortez Sail sets up the whole bloody drama of Mexico and the American Southwest from the fateful moment four hundred years ago when Spanish galleons bearing conquistadors ready “to slaughter for gods and for gold,” made landfall in Mexico, sealing the fate of the Aztec warriors who “watched from the mountainside with a fear in their eye as clear as their end that was near.”

Christian mythology, in the form of thundering skies over the crucified Christ nailed to a Dogwood tree, is laced—as it must be if we’re talking about America—throughout the tale of Juarez. Crooked, gold-plated judges and cops in dark glasses with slicked-back hair share the American landscape with lying bitches and their puffed-up testosterone daddies. This is California, and as Jabo, the raging narrator of There Outta Be a Law against Sunny California, proclaims as he leaves the Golden State in the wake of his exhaust, “as long as you people are gonna sanction such an evil, I’m gonna turn your asphalt back into brimstone and you goddamn better bet I will.”

Juarez and Lubbock (On Everything) emerge from the historical American soul that brought the Beats to life and animated the nihilism of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek’s characters Kit and Holly in Terrence Malick’s Badlands. In a 2012 interview Allen said that Dylan changed everything for him and for American culture. Dylan’s Nobel Prize win this year would seem to put a kind of headstone on this last, wild rock-n-roll century. One more operatic movement in the history of America comes to a close. Something new is on the horizon.

*****

If Juarez paints in the grandeur of broad, sweeping strokes, Lubbock (On Everything) is a more specific, more autobiographical album of sharply observed individual portraits. In Rendezvous USA Allen depicts a business man in a bar whose “life, like his drink, is on the rocks.” In Blue Asian Reds Allen sings about a woman “with red eyes from doing red pills.” The song reveals that the woman lost her man in ‘Nam and describes a year of crying and grief that finally drains her of any will to live. The song ends when the pills and alcohol finally kill her. The poetic clarity of Allen’s language and the empathy that never becomes condescending toward his characters give dignity and honor to the stupid, confused, heartbroken idiot in all of us.

The easy, loping rhythm of Flatland Farmer paints a picture of American folk art. Singing about rural bluesmen who play for crowds from their front porches Allen writes that the flatland farmer who “flat-picks an old guitar” “don’t make no money,” but can “out-sing, out-pick, out-play, out-drink, out-pray and out-lay any of them Nashville stars.” This song describes a historical moment in the early days of rock-nroll when folk music came out of the countryside to become the most authentic form of American art, but it’s also a poke in the ribs for slick poseurs who get the mechanics but don’t understand the soul of art.

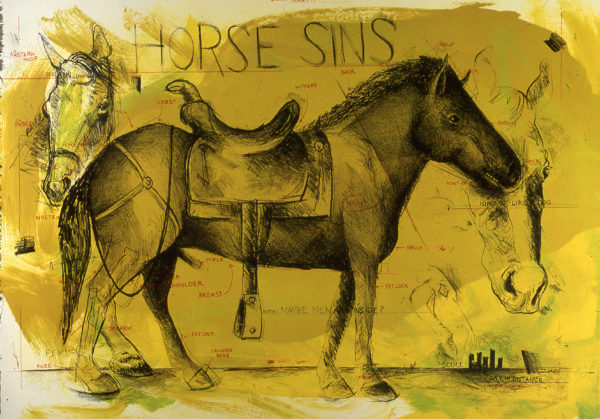

My favorite bit of writing in the Lubbock record comes at the end of the song The Beautiful Waitress. After describing a flirtation with a truckstop waitress over a bowl of chili, the artist-narrator has a conversation with her about art. When she asks him what he does, Allen replies that he tries to make art. Any money in it, she asks? No. To do that you have to teach. She says she likes art but “can’t draw a straight line.” Allen tells her that it’s easy to draw a line that’s straight enough but she says that she’s interested in drawing horses. Allen replies that they’re pretty hard to draw. “This is very true,” she replies. She tells him that she’s good at the body but things go awry with the head, the legs and the tail. Allen tells her she’s “drawing sausages, not horses.” “No, she said. They were horses.” What a great art conversation. It’s true too. Horses are hard to draw, especially the head and legs.

It’s true that people are products of their national circumstance. Things like class and race are forced on us from the get-go. We don’t have a choice about how we enter the world. We’re pretty much just tossed into the earthly mix, and we sink or swim. And if you’ve ever seen a newborn baby it’s pretty clear we come in under duress. Born in Lubbock or some other Siberian wasteland, man has always had to survive with what he has where he is. The characters in Allen’s music never really expect the world to treat them fairly because they’re either too smart or too broke to believe that it ever will. It’s all they can do to hold on with a little dignity and humor in the face of the bloody injustice and heartbreak that surrounds them. For these characters love is a rare gift, easily broken and often lost. This is the world I recognize. The flavor of this human fever-dream is American, but it’s also universal, because it’s deeply, eternally true.

2 comments

‘National circumstances’, as you call it, definitely influences a person’s life greatly, but shouldn’t determine it. It’s how you deal with it later on and use that legacy is what counts.

Michael, I occasionally take issue with your criticism, but I have to say that this essay on Terry Allen and his work is the best description I’ve read on an icon of American music and art. Thanks.