Sandy Skoglund (b. 1946) is best known for her meticulously constructed set-like interiors, filled with carefully chosen furniture, objects, and sculpted figures, all in shocking and contrasting color combinations. Her most famous artworks are the photographic prints depicting these super saturated and unabashedly artificial scenes. Radioactive Cats and Revenge of the Goldfish (1980-1981) are two of her most-reproduced images.

My love of Skoglund’s work was rekindled in 2021 when I reviewed the exhibition Limitless! Five Women Shape Contemporary Art at San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum. The show featured Skoglund’s Cheez Doodle-packed installation, and McNay acquisition, The Cocktail Party (1992), along with the more recent and immersive Winter (2018). When Bale Creek Allen told me Skoglund would be back in Texas for his Fort Worth gallery’s presentation of The Outtakes I jumped at the opportunity to talk with her.

Erin Keever (EK): I became familiar with your work, along with that of several other female photography artists including Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Sherrie Levine, in the 1990s. Like Sherman, your work involves staging. But unlike a lot of photographers and artists of that time, you pretty much steer clear of appropriation. Is there any kind of background to that?

Sandy Skoglund (SS): Absolutely. It’s the foundation of my work really, to not appropriate. Philosophically the zeitgeist of the moment was that originality had been fully explored. So, it was an exercise in futility to try to express yourself. To me, that attitude of why bother, or don’t even try, because it’s not possible, leads to a state of cynicism.

Fundamental to my work is this understanding, and working with a combination of finding things and making things, but never finding things to essentially mock my own culture. It is too painful for me to take that attitude. I don’t feel it. It’s important for me to feel whatever my feelings are and for those to be carried into the work.

Prior to Radioactive Cats, I was doing food still lifes. They were satirical exercises of commercial food photography practices, which reflected the changing society from the modern period to the postmodern period. In 1978, commercial practices were more interested in reaching out to the viewer than the art galleries were, where art was very white, in white spaces, and almost impossible to understand. A real philosophical blank wall was presented to the viewer going into the gallery. And I say that with the authority of someone who did that work in the 1970s.

Although, at the time, I had no respect for photography.

With the still lifes, I found the process to be fun, humorous, and ironic — my behavior as an artist going to the grocery store, going into the freezer area, buying the frozen peas, unpacking the peas, and pulling out the perfect peas really echoes the practice that goes on in commercial food photography. So back to your question, yes, most of the people of my generation were critiquing commercialism. They were saying things like, okay, the Marlboro man is fake.

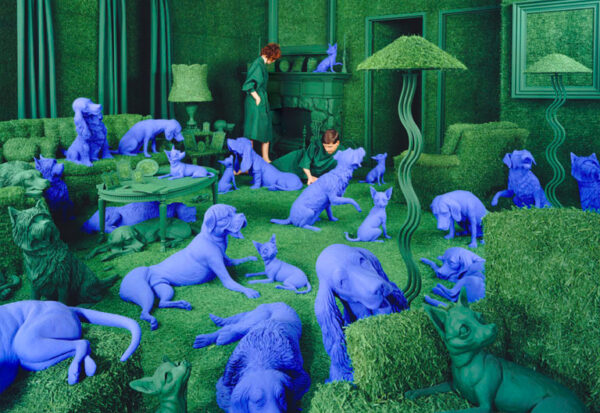

Sandy Skoglund, “Wishes and Whispers,” 1994, from “The Outtakes,” on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery

EK: Okay, chicken, egg. Is the photo the central goal, and the installation a way of achieving it? How does that work in your mind? How does the process of creating an installation relate to your photography?

SS: The process is sequential. I have an all-encompassing idea. Usually, it comes after a long period of time and editing out other ideas. All my works have some form of sculpture, but let’s say I’m making the sculpture, that’s the first thing that I would be involved with, and that would take a lot of time, which is very precious to me. What is my experience doing my own work? I mean, why be an artist? It’s really the feeling of doing it.

EK: I’m realizing how elevated sculpture is in your process, and not sure I was certain the sculptures were handmade versus being machine fabricated. Can you talk about your sculptural figures a bit more?

SS: I rented an apartment on Elizabeth Street in New York City, painted it gray, and set up the four-by-five camera looking at the blank room. I decided that I wanted to do something with found objects. There are some early works done in the apartment with plastic spoons and things like that. Those then led to the idea of a cat in Radioactive Cats. Where do you get the cat? Whose cat is it? Is it going to be a sculpture of a cat? Obviously it couldn’t be a real cat, because the fun for me in my work is being able to control where everything goes. I thought, I’ll just make a cat. It can’t be that hard. And well, it was hard. I started to sculpt the cats in direct plaster, and it was that decision to not kind of cynically just go back to the store and instead, push on making them in plaster. It felt like a personal investment and changed the direction of my work.

EK: Today everyone talks about “practice” and “artistic practice,” and I think that’s what you’re sort of talking about. I mean, the work is a practice that you get on with, and potentially repeat. But getting up and doing it is part of being an artist.

SS: Yes, but there has to be enthusiasm. The drive part is another part of your being. There’s an emotional part of the work that leads you in that direction, and you don’t want to let go of that, even when it’s repetitive. The repetition makes it even better. Children love repetition. Okay, repetition could be repetition in a factory. Let’s be clear that mechanical reproduction is not the same as human repetition. What I discovered in sculpting, which I hadn’t really discovered before, was that you get better. With the cats, I made one cat or goldfish or whatever and every day that I woke up, it was like, this one needs to be better than yesterday. It’s that sort of belief system, I guess.

Even when I was a conceptual artist doing repetitive mark making, like Agnes Martin, during the minimal period, that attracted me. I would do things like take a pencil and sharpen it once and spend weeks making dots on a huge canvas. The pencil lead grows, becomes thicker and thicker, wider, less sharp, and repetitively, I would cover the whole thing.

Sandy Skoglund, “Beyond the Door” an “Outtake” from “Radioactive Cats,”1980, from “The Outtakes” at Bale Creek Allen Gallery

EK: Those were in black and white. How did you make the shift from the monochromatic conceptual work into the high chroma photography?

SS: The shift from conceptual work was abrupt. What I didn’t like was the idea of art being a form of information that was class-oriented and exclusionary. I was reading books on the avant-garde, trying to think about, “here I am like an American woman, 1970, what should I be doing?” Originally it was the idea of “let’s throw the object out completely and essentially reduce the work of art to our brains,” which was quite radical. And it felt in practice as though it was self-destructive and unhealthy for me. I mean, other people can do it, I’m very appreciative of the work, but this is back to the emotional center for me of being an artist.

At one time, I wanted to be a film director. And from Smith College I had to go home to Naperville, Illinois, and get a job. I worked teaching art at a junior high school in Batavia, Illinois, for one year. Batavia was the end of the world, like the Antarctica of the art world. That did it for me in terms of film, meaning I realized I have to do something that I can do myself.

When I went to graduate school, I tried all kinds of things from printmaking to painting. Color field painting was very big — post painterly abstraction. There was a lot of splashing of paint and that kind of thing. Color was always there, among my colleagues. When I got to New York and became interested in conceptualism again, I went immediately into color photography, teaching myself.

EK: Your colors have a quality to them that’s not even post painterly abstraction, though. I mean, some of them are borderline garish. They’re so distinguishable, a signature really. How do you make those color choices?

SS: The thing I’m really interested in is beauty. To my eye, they’re beautiful. Also, I would say my focus on using color is wham! I mean, it’s an assault to the senses. I’m deliberately trying to destroy the space — there’s no doubt about it, in the repetition and the patterning — not in every single piece, but definitely in the earlier work.

EK: Nearly every write-up on your work describes it as surrealist, which feels so overused and mis-used. Your work reveals aspects of invention and fantasy, but do you consider it surrealist? Are you interested in revealing hidden drives or the unconscious? What’s your relationship with Surrealism?

SS: That’s a good question. I always feel that that resemblance is too generalized. Anything that looks strange is called surreal. In a good way, it means that surrealism has gone all the way from high culture to the American middle class. I like the surrealists but I’m not any more drawn to them. A lot of the genuine, original surrealist work is quite dark in spirit, which you don’t see in my work.

“Moody Calm” (1990 / 2022) by Sandy Skoglund, from “The Outtakes,” on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery

EK: Your works have a seductive spatial sense, and you obviously work inside of the scenes, the sets, the environments. I’m curious what it feels like to be inside of one of them. Do the models ever talk to you about it?

SS: In the early days, the models were people that I knew quite well in New York. When I first decided to work this way, all the effort was on the sculpture, and I was deeply inspired by Edward Kienholz and George Siegel. You see a photo of their work, and you kind of know their work. You kind of know how big it is, the scale. There were people doing miniatures and photographing that, but one thing I did not want was for people to look at my work and think it was a miniature; it’s not like a diorama or something — it’s big enough that you can walk into it. It’s a real space.

I took the early work with and without people within the space, but I came to see that figures were important. If the image gets separated from the work, from the sculpture, which it will, then you’ve lost your sense of scale. This is partly because the spaces are so unreal. If it were maybe a realistic space, then I don’t think you need it. Like photographs in Architectural Digest.

The way I was transforming the spaces required that there be a person. In Radioactive Cats, the older woman was my landlady. The guy sitting in the chair was a friend of mine who swept the sidewalks. I had them just come in, walk over, sit down, stand over there, click, click, click, and let them do a few little things. That’s it. Of course, I gave them a little bit of money, and that was how it started, really. But no model has ever really sat down and talked about it.

EK: Shifting to the work on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery, tell me about The Outtakes and the project’s inception.

SS: It began about six months after COVID really hit, around the time of the shutdown. I was by myself, in Jersey City, and I was just feeling pretty elated by the ocean of time, because everything was canceled or postponed. We had no clue how long it was going to last. I remember the conversations were, “when this ends, we’ll do this or that.” There were no expectations. I could do anything. It didn’t matter. No one was going to see it. No one was going to care. A lot of people I knew pretty much kept going. I would say, of course, the pandemic came into their work, but I just stopped. It was a really strong creative pause for me.

I have a large storage area and I was going through my archives and straightening up the office part of the studio, and I was seeing these piles of outtakes, of transparencies that were rejected images from the photo shoots of each of these 12 images. There were many more, of course, but these 12, represent The Outtakes. I’d be going through the images going, “oh, I wonder…” even though it’s been 43 years.

EK: Could you remember any of your reasoning behind why you rejected them? Did that influence why it was important to revisit the work?

SS: The whole thing was like looking at a person that I wasn’t anymore, time traveling backwards. I knew why I chose the original picture; that I was absolutely, completely clear about.

I felt like some of these outtakes were genuinely different, said something different, and deserved to live. Basically, the poor things deserve to live. I was talking to Robert McAn at the Kimbell Art Museum, and I said, “I mean, I’m not a mother, but they really felt like children.”

EK: Like a Sophie’s choice thing — pick the one and leave the other behind.

SS: Right, right. So that’s the sort of psychology behind it. And then it just kept growing in terms of choosing the one that I felt was the furthest away from the original choice. The furthest away in content, meaning, and feeling. They’re drastically cropped — the originals were always the full shot, the full 4 x 5 or 8 x 10 film. These are cropped to focus much more on the people. Whereas in the early pictures, you have to really look hard to find a person. That was deliberate. As for the smaller sizing, they are the largest prints I could make. During COVID the lab was closed, and I bought a printer, and these are the largest that I could make with a desktop printer.

EK: I have to explain to my students about contact sheets. Some aren’t aware of the concept of negatives.

SS: It’s true. There’s been a sense of loss, no doubt about it. I’ve done a few installations that were just digital, taken with a high-end digital camera, with no negative, no transparency. But your commitment, it’s a different commitment. These were outtakes, I mean, at least they made their way onto film. Whereas the digital stuff, it’s like, how can I put it? Since there’s no material existence in digital imagery, there is not a whole lot of human commitment.

EK: Your commitments extend to your teaching. I can’t believe you’ve been teaching for close to five decades and at Rutgers University – Newark, where you are a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Arts, Culture and Media.

Also, you’ve obviously exhibited internationally, but it seems your work has been getting some traction in Texas recently. Is there a connection?

Sandy Skoglund, “The Company of Others,” 1990-2022, pigmented ink print, 16 x 20 inches (19.5 x 25.2 inches framed), edition of 30. This work was on view at Rule Gallery in Marfa, Texas in 2022

SS: I think it’s the sensibility. I’ve lived in a lot of different places — Maine, Connecticut, and California as a child, Massachusetts, Iowa (for grad school), and New York. Texas came much later. My dad worked for Shell Oil. He retired here, and my husband and I married down here in Humble.

The original connection was very art world, meaning the artistic connection was the gallery I was working with in New York. The gallerists and museum people from Texas were seeing my work in New York, and they were showing it here in the 1980s. For example, my work appeared in the FOCUS exhibition series at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, when it was called the Fort Worth Art Museum in 1981. And I also showed at Texas Gallery in Houston. I think there’s a sensibility here that’s interesting to me. It does seem like the audience here gets my work. Certainly.

EK: One last question. The art historian in me had to pull some books off the shelf prior to our interview. I was looking at Naomi Rosenblum’s History of Women Photographers (Abbeville Press, 1994.) Rosenblum wrote, “The unnaturally saturated colors and manic accoutrement in the invented interiors depicted by Sandy Skoglund proclaim and even satirize the sets and strategies of the advertising industry. Skoglund herself claims a more complex purpose, however, suggesting that these works deal with a centrality of human life and the relationship of photography to death.” Can you tell us more about this?

SS: Wow, God bless art history. I did an essay on photography and death. I didn’t love the field of photography when I entered it. I entered into it as an outsider. Then I learned the techniques and used them the way I wanted to. I keep thinking about how lucky we are to have it; how lucky I am to have it. One of the things that is unbelievably tragic about life is death. And what is death? It’s disappearance. Someone who is alive that you knew was alive, you knew them. Now they’ve disappeared. They’ve totally disappeared. Before photography, things just disappeared. And maybe they were preserved in different ways in their sarcophagus or drawings or what have you. But now we have this medium that’s kind of a mirror of things that have disappeared. And I find that to be almost a religious experience.

The Outtakes is on view at Bale Creek Allen Gallery through October 31, 2023.

3 comments

Love this interview. Thanks!

What an insightful interview–such thoughtful questions. I had the great pleasure to meet Sandy Skoglund who was the keynote speaker at one of the many conferences I chaired for Society for Photographic Education in the MidAtlantic region. She is a true inspiration.

Great show. I met her briefly, but this interview adds depth. Thank you for the insights.